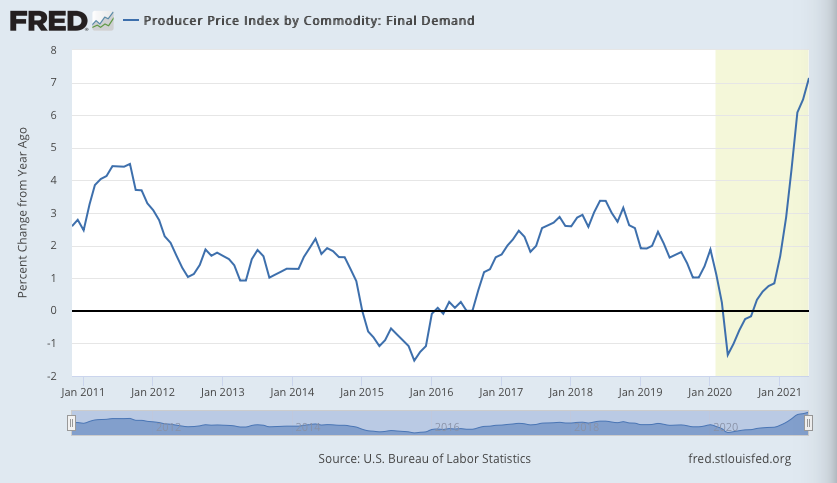

Regarding inflation, it's good to define transitory vs. persistent. Transitory would be the next several months, to the end of the year. Persistent would be the next decade.

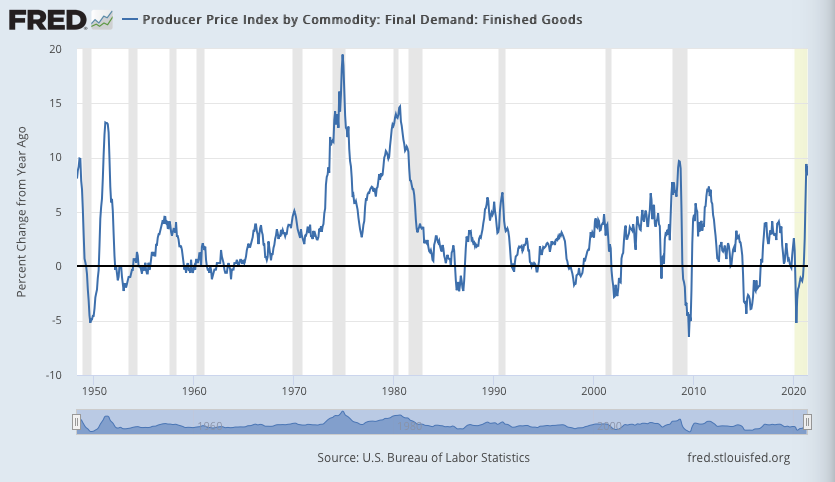

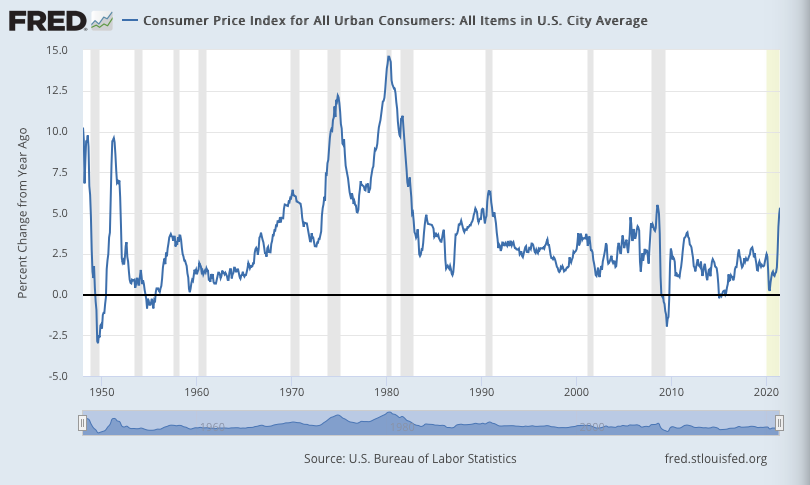

When trying to understand the economy, we tend to refer back to historical experiences as our model. In the case of inflation, for most of us, the go-to reference is the experience of the 1970s.

But there are other historical models that may capture the situation better. I'd argue it's possible that our current experience of inflation bears less resemblance to the inflation of the 1970s than the surge in inflation immediately after World War II.

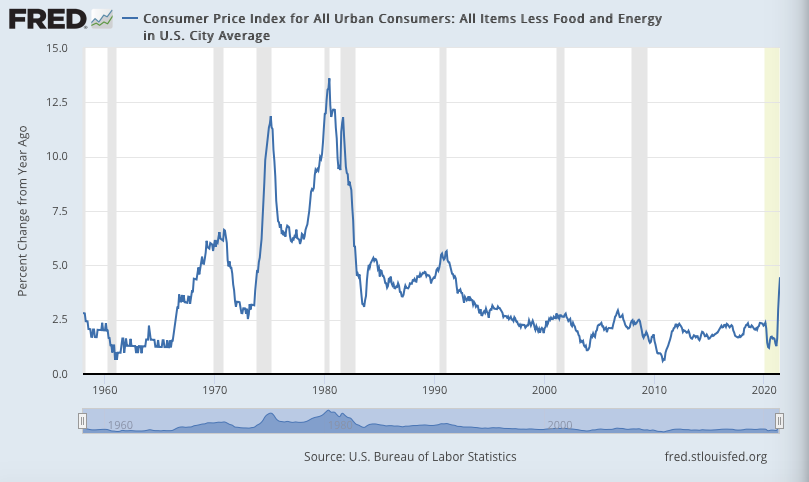

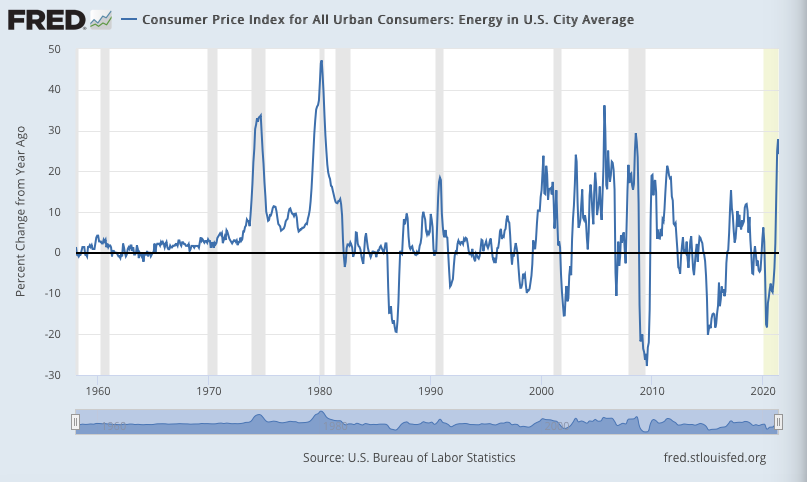

The inflation of the 1970s, I'd argue, was the product of long-term constraints on supply, including energy scarcity and stifling regulation. Hence it coinciding with lower growth rates -> stagflation.

The sharp post-WW2 bout of inflation consisted of two things: a sudden resurgence in consumption, and a massive and disruptive conversion of supply capacity. I'd argue there are strong similarities to the demand stimulus and supply chain/labor market issues we face right now.

The post-WW2 inflation surge was sharp and, at the time, very alarming. It did not last, however, because the disconnect between demand and supply was able to get worked out.

Whether this proves an accurate comparison or not, time will tell. But it's worth keeping in mind that there are a wealth of historical reference points out there that may prove relevant, not just our most recent (and for some lived) experience.

The one factor that makes me concerned about structural inflation going forward is the (possible) retreat from globalization. The supply brought online by globalization in China, India, and elsewhere has played a key role in keeping prices of all kinds subdued.

If that dynamic changes, and that long-term disinflationary pressure recedes, it could prove more enduring than whatever supply/demand mismatches we are experiencing post-COVID.

As BOTH the post-WW2 and 1970s experiences with inflation show - in opposite ways - a long term investor should care less about inflation over the next year and more about inflation over the next decade

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh