Summer 2021 has seen record heat waves (and the hottest June on record over land regions), as well as extreme flooding. In our Q2 2021 State of the Climate update, we look back at the first six months of the year and what the next six months may hold: carbonbrief.org/state-of-the-c…

Despite record summer heat in some areas, globally the year has been a bit cooler than the last few so far; 2021 is the seventh warmest year on record to-date. That still means its warmer than all but seven years since record began in the mid-1800s!

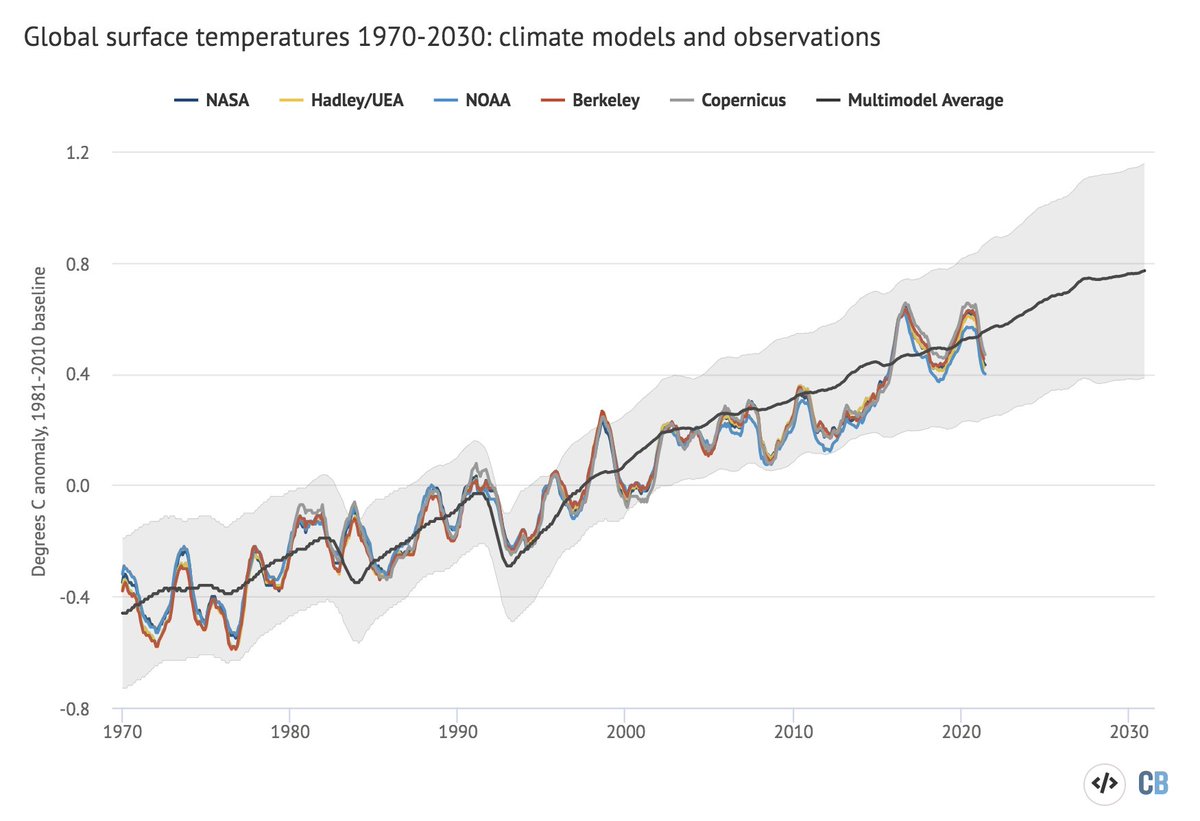

Here is 2021 to-date in context of the long-term warming across the five major global temperature records (NASA, NOAA, Hadley/UEA, Berkeley Earth, and Copernicus/ECMWF):

Based on the first six months of the year and the El Nino/La Nina forecast, we can estimate where 2021 will end up. We find that it will very likely be somewhere between the 5th and 7th warmest year on record, consistent with the long-term warming trend:

This suggests that the remaining months of the year will likely be a bit warmer (in terms of temperature anomalies) than the first six months of the year, driven in part by the fading La Nina event that drove down early 2021 temperatures:

Global temperatures are pretty well in-line with where climate models in the last IPCC report (published in 2013) projected they would be:

Finally, Arctic sea ice has been at record lows for this time of the year for much of July, though it is too early to tell what the September sea ice minimum will end up being. Antarctic sea ice has been pretty normal (relative to the 1981-2010 period) so far this year:

For more details (and more on recent climate extremes), read the Q2 2021 State of the Climate article: carbonbrief.org/state-of-the-c…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh