Why cities drove change in pre-industrial British agriculture, A THREAD (and newsletter daviskedrosky.substack.com/p/london-calli…): #EconTwitter #econhist

I've recently been privileged to join in some fun discussions with @pseudoerasmus and @antonhowes on the path of British development. 1/7

I've recently been privileged to join in some fun discussions with @pseudoerasmus and @antonhowes on the path of British development. 1/7

Pseudo, following Robert Allen and E. A. Wrigley, has been strongly emphasizing his argument that autonomous development in British trade and manufacturing provoked productive responses by farmers, allowing for structural transformation. 2/7

https://twitter.com/pseudoerasmus/status/1422283254472839172

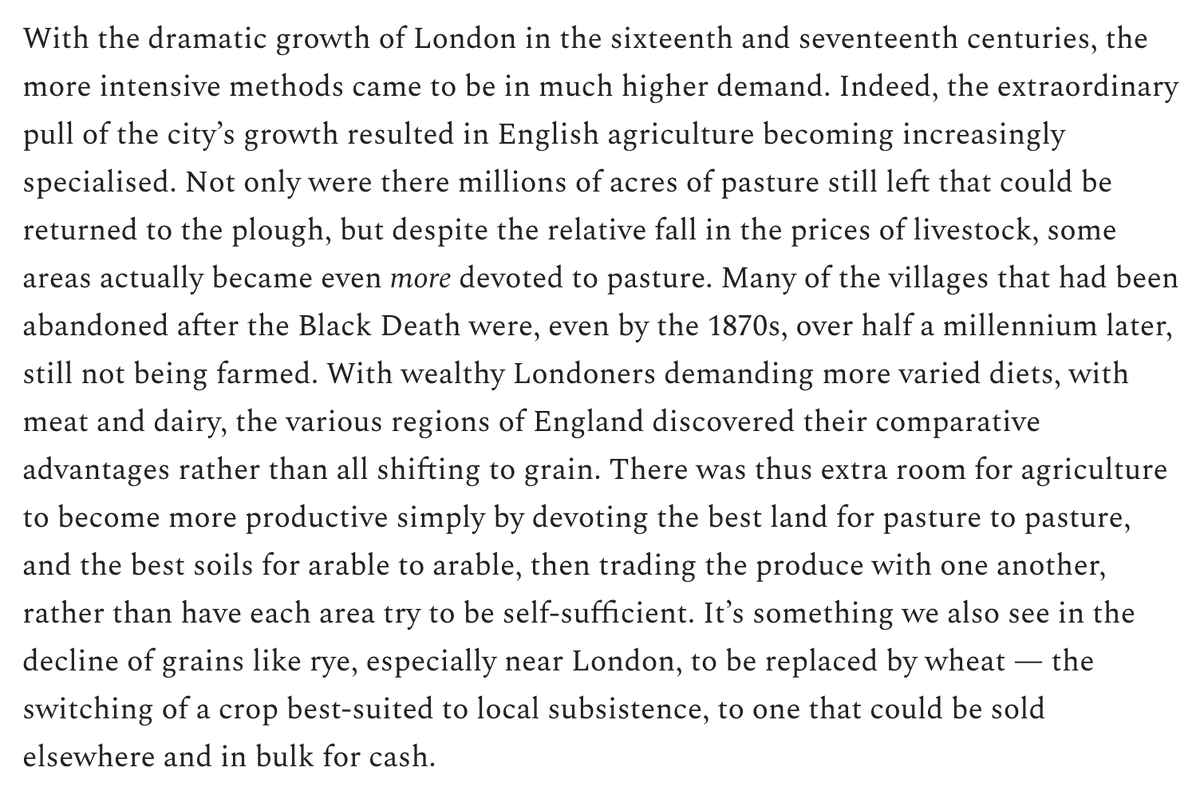

Anton has made similar arguments in his blog, emphasizing the role of a growing London in promoting specialization by comparative advantage in the English countryside. 3/7 antonhowes.substack.com/p/age-of-inven…

I try to synthesize elements of this discussion against the contrary view (of O'Brien, Crafts, and Harley) that independent organizational/technical changes in agriculture (e.g. enclosure) were necessary to provide fuel and manpower for the cities. 4/7

I also argue that growing English towns, particularly London, drove up the prices of farm products relative to manufactured goods, encouraging farmers to make improvements and cultivate their lands more intensively. 5/7

Since slack labor, often employed in handicrafts, was common in the British countryside, resources already "within" agriculture could be redeployed to feed the cities, allowing the rural share of the population to decline (a la Weisdorf 2006). 6/7

This contribution is not at all definitive, but rather an attempt to put together a few thoughts in defense of their compelling and—in my view—quite probably correct theory of British development. 7/7

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh