THREAD+NEWSLETTER: Urban demand, NOT agrarian capitalism, drove city growth in early modern Britain. 1/

If you enjoy this, please share! I rely primarily on word of mouth for spreading the good word. daviskedrosky.substack.com/p/london-calli… #EconTwitter #econhist

If you enjoy this, please share! I rely primarily on word of mouth for spreading the good word. daviskedrosky.substack.com/p/london-calli… #EconTwitter #econhist

A classic view of British industrialization, dating back to Marx, holds that autonomous change in agriculture—enclosures, private property, large farms—increased worker productivity, supplying the growing cities with labor, food, and raw materials 2/

Crafts and Harley (2004), for example, find that French-style peasant farming would have had a significant "deindustrializing" effect by lowering urban employment.

The implication: capitalist farming permits city growth and explains British structural transformation. 3/

The implication: capitalist farming permits city growth and explains British structural transformation. 3/

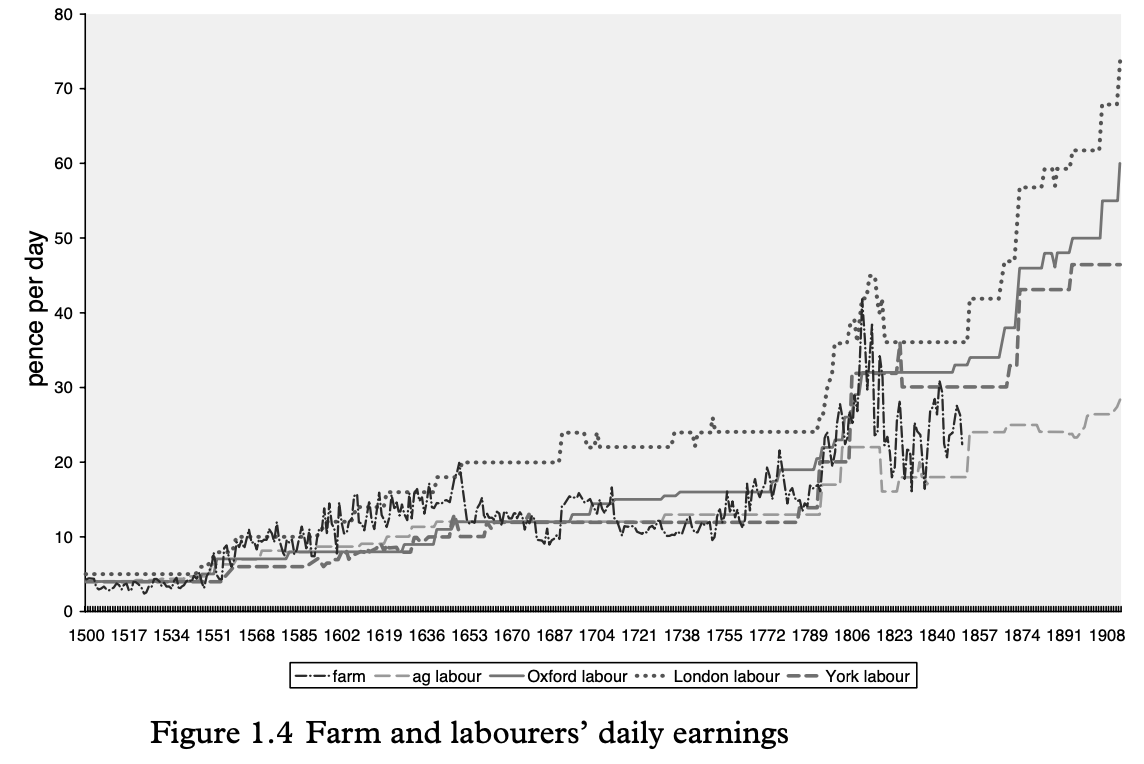

But the evidence is lacking. Enclosures barely increased farm output, especially when turning arable to pasture, and many workers—as evidenced by a widening rural-urban wage gap—were not released, but rather remained unemployed in the countryside. 4/

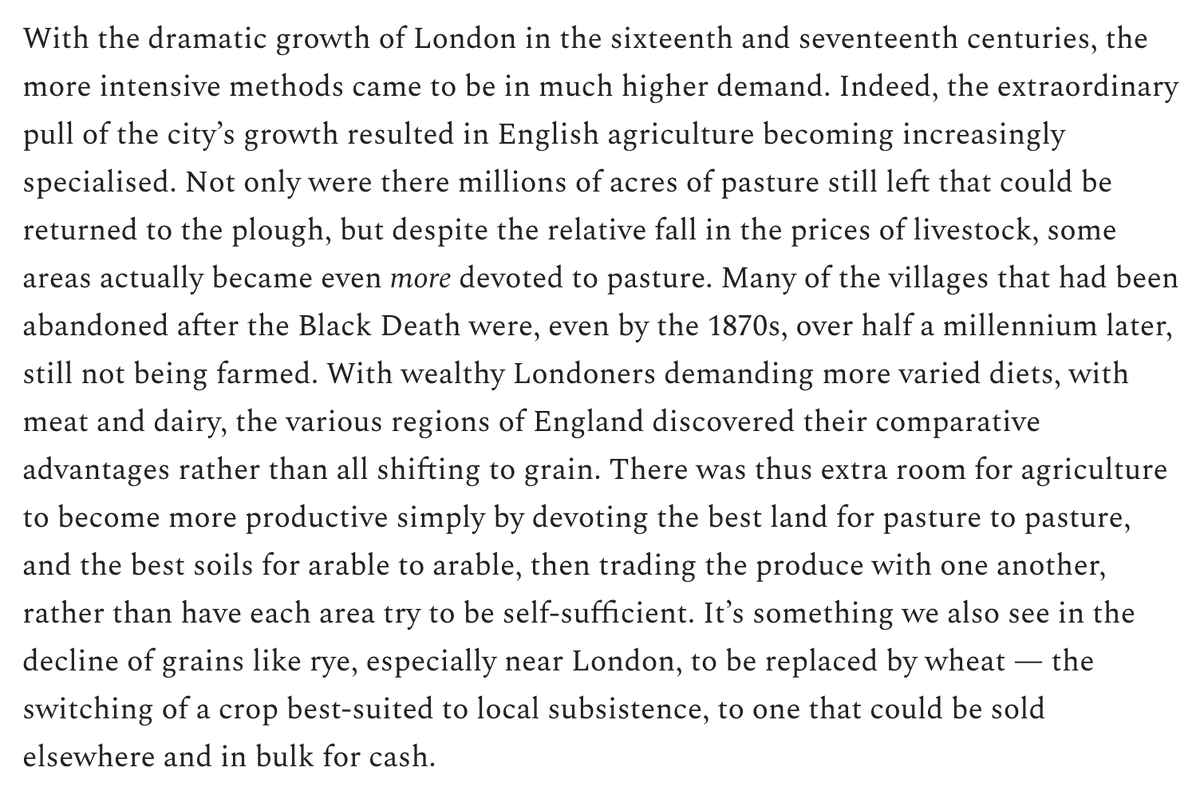

Causation ran the other way. Urban demand from Britain's high-wage cities raised agricultural goods prices. Favorable terms of trade led farmers to cultivate intensively and specialize by comparative advantage (a la @antonhowes), buying manufactures rather than making them. 5/

Simulations by Allen (2003) show that enclosures had next to no effect on urbanization and that external trade and manufacturing productivity drove most British city growth up to 1800. 6/

To explain why Britain moved out of agriculture so early, then, we must explain her exceptional success in trade and various urban industries, viewing agricultural change as generally a response to these developments. 7/

Once again, if you find this newsletter valuable, please do send it to anyone who might be interested (and subscribe yourself!). You are collectively my sole means of getting this before a wide audience. #econhist #EconTwitter

daviskedrosky.substack.com/p/london-calli…

And, as ever, thanks! 8/

daviskedrosky.substack.com/p/london-calli…

And, as ever, thanks! 8/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh