Amazing new paper by @amirrkermani @francisawong on the racial gap in housing returns.

Black and Hispanic households see their housing wealth grow less, contributing to the overall racial wealth gap substantially.

Black and Hispanic households see their housing wealth grow less, contributing to the overall racial wealth gap substantially.

The large raw differences are mostly about differences in borrower characteristics, particularly about *place* of purchase.

The returns gap is 1) amplified by high leverage and 2) entirely concentrated in distressed sales (foreclosures and other sales arising out of delinquency).

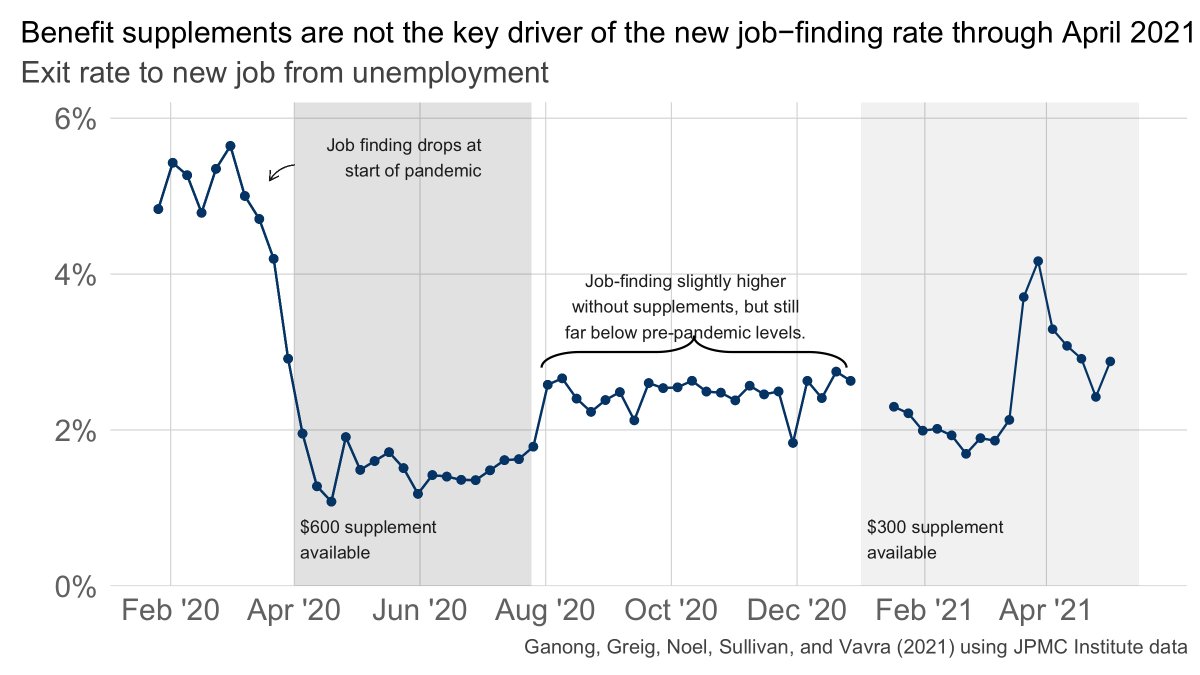

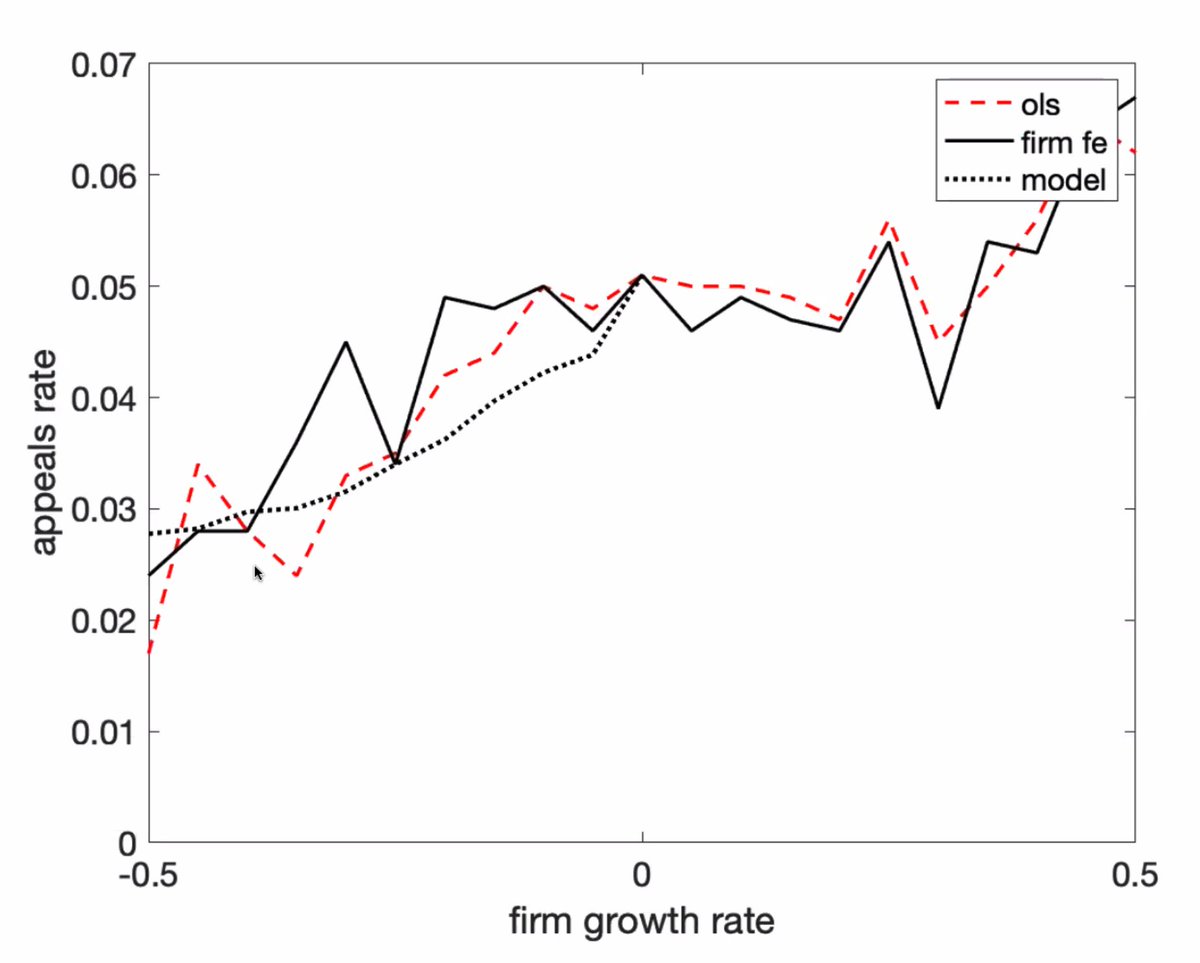

Because distress sales arise from liquidity / cash flow shocks, this means that more volatile labor income increases foreclosure risk.

The paper therefore shows how the labor market, fed through the mortgage market, makes it hard to use housing to close the racial wealth gap.

The paper therefore shows how the labor market, fed through the mortgage market, makes it hard to use housing to close the racial wealth gap.

The paper might therefore be called "the foreclosure crisis strikes back" because it's about how the foreclosure crisis, which hit black and brown communities particularly hard, also did long term damage by increasing the racial wealth gap.

Full paper here dropbox.com/s/8s9zvd39wk7g…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh