1/ Fascinating

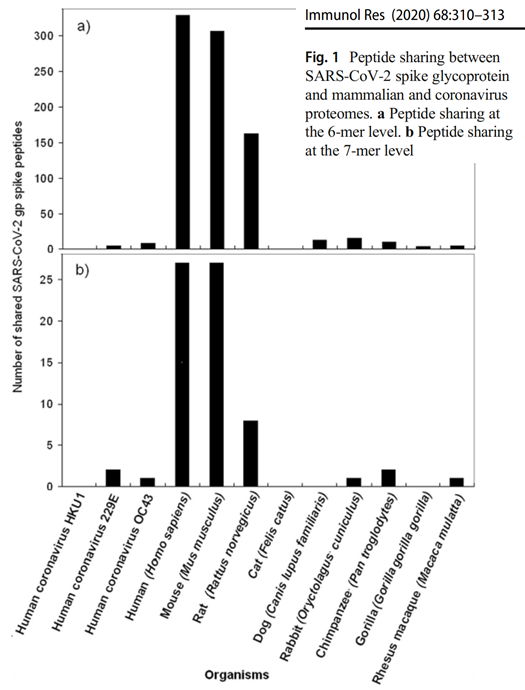

Fig 1 of Kanduc & Shoenfeld (2020) uses a very simple analysis: shows that CoV-2 shares many 6-chain amino acid sequences with human and mouse genomes, but not other genomes such as cow, pig, gorilla, chimp, rhesus monkey, fruit bat

doi.org/10.1007/s12026…

Fig 1 of Kanduc & Shoenfeld (2020) uses a very simple analysis: shows that CoV-2 shares many 6-chain amino acid sequences with human and mouse genomes, but not other genomes such as cow, pig, gorilla, chimp, rhesus monkey, fruit bat

doi.org/10.1007/s12026…

2/ The same applies to polio, measles, dengue, influenza H1N1, smallpox, HPV, and Ebola viruses. Also bacterial pathogens like anthrax, plague and toxoplasmosis; all overlap more with mouse (and rat) than other animals.

3/ This implies we have frequently swapped pathogens with rodents - which we live very closely with. (Apparently bat experts say bats have the most dangerous viruses. But rodent experts say THEY, rodents, harbour the worst viruses!)

4/ But CoV-2 doesn’t bind well to mouse ACE2

This strongly suggests

(a) CoV-2 has undergone many cycles of replication in humanized mice engineered to express human ACE2 (lab-leak)

Or

(b) CoV-2 has been in humans for years, & before that it was in mouse-like rodents, not bats

This strongly suggests

(a) CoV-2 has undergone many cycles of replication in humanized mice engineered to express human ACE2 (lab-leak)

Or

(b) CoV-2 has been in humans for years, & before that it was in mouse-like rodents, not bats

5/ Note that chimp doesn’t overlap much with us – presumably because our/their sequences have changed to avoid infection in the last 6.5 million years

This implies that fruit bats may also be rather different from eg horseshoe bat in their sequences

This implies that fruit bats may also be rather different from eg horseshoe bat in their sequences

6/ Kanduc & Shoenfeld don’t show us the CoV-2 overlap with horseshoe bat. We’d like to make the comparison of that overlap with the mouse one. Maybe they’ll publish that soon

7/ For those without biological backgrounds:

1. the most important defenses against viruses are T cells, not antibodies (since viruses spend most of their time INSIDE cells)

1. the most important defenses against viruses are T cells, not antibodies (since viruses spend most of their time INSIDE cells)

https://twitter.com/PatrickSSte/status/1320334959777882112

8/

2. The immune system chops up viral (& other) proteins in cells & “displays” the bits on the cell surface

3. T cells kill cells displaying foreign bits

4. Viruses have cottoned on to this. They use some of our sequences –because we don’t (can’t) recognize 'em as foreign

2. The immune system chops up viral (& other) proteins in cells & “displays” the bits on the cell surface

3. T cells kill cells displaying foreign bits

4. Viruses have cottoned on to this. They use some of our sequences –because we don’t (can’t) recognize 'em as foreign

Private communication: apparently we don't yet have enough well-reviewed proteomic data for horseshoe bat to make the comparison

You might think that was rather important

You might think that was rather important

Links to the three papers by Kanduk, and Kanduk & Shoenfeld:

CoV-2 doi.org/10.1007/s12026…

Bases thieme-connect.com/products/ejour…

Pathogens inc influenza thieme-connect.de/products/ejour…

CoV-2 doi.org/10.1007/s12026…

Bases thieme-connect.com/products/ejour…

Pathogens inc influenza thieme-connect.de/products/ejour…

Is something else going on? Didn't measles come from cattle about 1000 yrs ago? So why no strong cattle signal there?

My interpretation of this data is that sequences that exist in the human proteome are rapidly selected in viruses because we lack T cell receptors (equiv of antibodies) for them.

(I thought obvious but other interpretations exist eg viral sequences have invaded human proteome)

(I thought obvious but other interpretations exist eg viral sequences have invaded human proteome)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh