Personally, I don’t agree with a lot of this by @julianHjessop. There is a whole question that has to be answered with regard the state of the transport industry going into the pandemic, and so far I have not seen it asked or answered.

(Thread: Part 1).

(Thread: Part 1).

https://twitter.com/jdportes/status/1431376740287451144

Please take note, Julian is my favourite Brexit economist who makes his arguments on proper economic principles, and therefore, please do not abuse him. I am, as he has done at other times before to other people, simply scrutinising his work.

Firstly, the article asks if Remainers can say they were right, and so I looked into what we actually said.

Remainers didn’t say that in a deal scenario there would be empty shelves, but what they did say was that Brexit would be additional pressure on the already weak freight industry, and it looks to me like they were 100% correct.

With the straw man aside, Julian’s next claim is that the US, the UK and the EU are all facing similar problems, and there is a source showing the US delivery times are more affected.

This is true, it does say that, but it also says that the Eurozone is proving more resilient, the US is suffering from the Deta variant, and it does not address the question of how much more resilient the UK economy would, or would not, have been in the EU.

In the next point, Julian highlights the fact the IRU have said that these shortages, which are global, would “soar” and that the pandemic was exacerbating long standing problems of poor pay, poor working conditions, and an ageing labour force.

It's important to note that the IRU were making the point that when the economy shut down, the logistics sector was under strain, and now the economy is reopening things are set to see demand “soar” back to their 2019 levels, an effect which would strain the sector further.

It’s a very good point and the economy will suffer because of it, but we’re not restarting the food and drink supply chains and supermarkets have historically been quick to point out how much of the chain is based on their own personal fleet management.

And any additional stress from the hospitality industry, it’s main rival, is just as likely to be seen at the farm, or the processing plants, due to shortages exacerbated by: Brexit.

With the supply chain weakened, the supermarkets did not experience empty shelves when their main supply chain rival “soared” into action in June, and there was no similar "soar" in July.

Julian has raised an great point, but it’s not necessarily applicable in this case.

Julian has raised an great point, but it’s not necessarily applicable in this case.

It is, however, true that the US is suffering shortages and their solution today is to make it simpler to recruit from other countries.

Germany is also having difficulties and is also responding by making it easier to recruit from other countries.

Brexit has made it harder to recruit from other countries and specifically the countries that were contributing to a large number of our recent recruits.

And that takes us to the “long standing problems” theory that I really want to focus on in this thread.

The free market never knowingly over paid and all industries have weaknesses, but it had been previously recognised by the government that the UK had a serious shortage of drivers as the result of a specific shock.

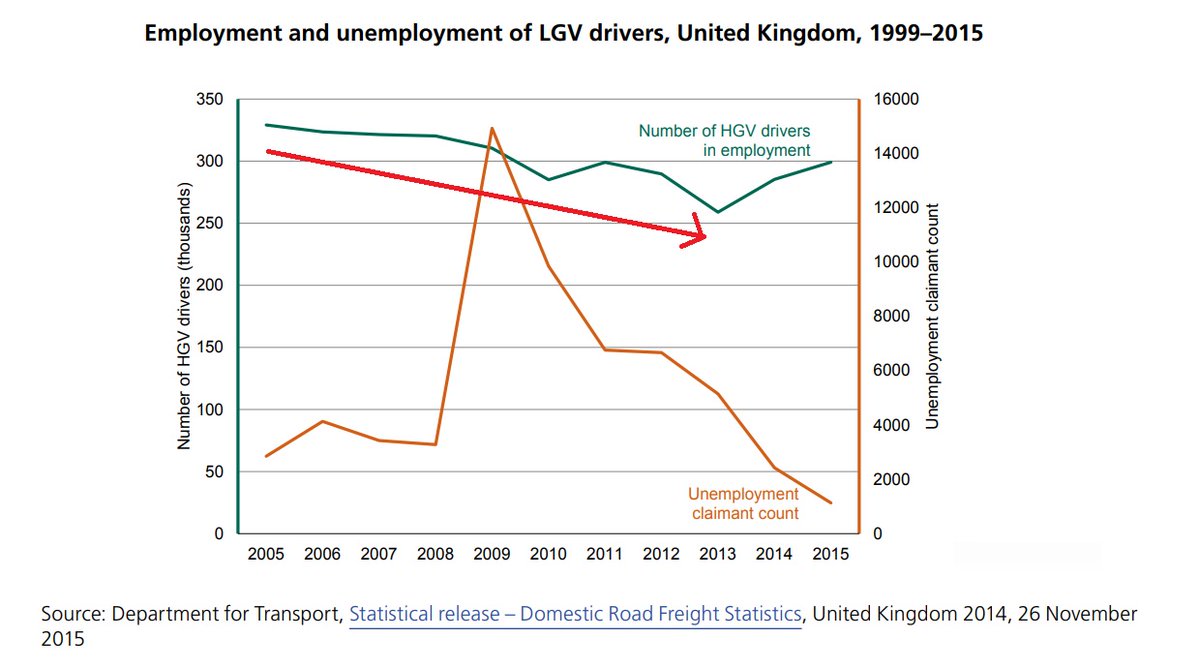

The shock in question was the introduction of the EU’s, driver Certificate of Professional Competence (CPC) which saw drivers across Europe question why they were having to qualify for a job they had been doing all their lives, and opting for retirement.

This effect can be seen in the data with a slow reduction up to the point when the certificate comes into force.

Leaving the industry at apparently tipping point with suggestions that failures are actually happening.

As Julian writes in this article, the free market adapts, and that’s why this, and any other analysis highlighting long term conditions, are off the mark.

As a result of both the government and the industry getting involved in this crisis, apprenticeship schemes or driving academies were run.

Along with trying to get young people in, they seek to recruit older people looking for career changes too.

And, of course, the industry look to Europe to recruit additional drivers and rely more on agencies.

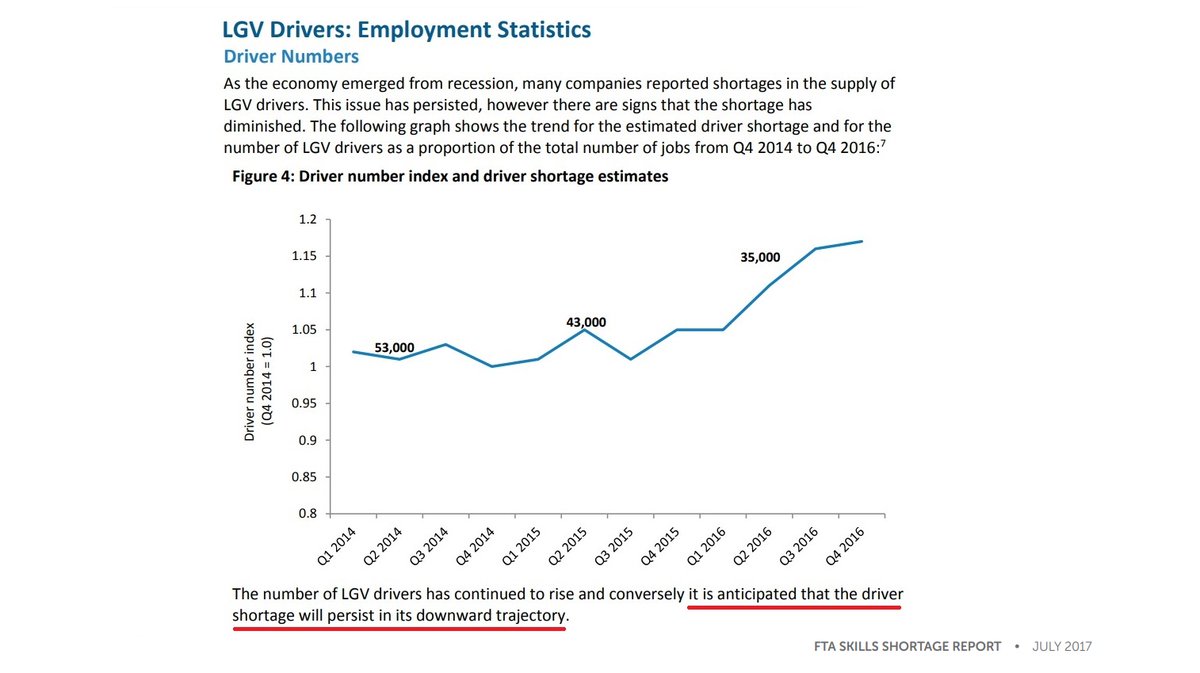

The initiatives are successful, and consequently, the Freight Transport Association (FTA) begin 2016 celebrating a significant dent in the LGV driver shortage.

Amazingly the FTA figures suggest that the number of people in the industry between the ages of 17-34 increased by a massive 14,492, which had also brought the average age down.

In a statement to the Chancellor, later in 2016, the FTA announced that, while the industry had become dependent on European workers, it was back to “pre-driver crisis levels” with a shortage of just 34,567.

And they go on to report in 2017 that they anticipate that the “driver shortage will persist in its downward trajectory.”

The “long standing problems” were not seen as big sticking point in 2017, it would seem.

The “long standing problems” were not seen as big sticking point in 2017, it would seem.

And suddenly there are reports that less people are applying to work in the UK.

One recruiter claimed they had received five times fewer applications for driver jobs since the vote for Brexit.

One recruiter claimed they had received five times fewer applications for driver jobs since the vote for Brexit.

And at the end of 2016, the FTA report that the recovery had stopped in the period Q2-2016 to Q2 2017, with growth failing to outstrip demand for the first time in three years.

It is the same period that sees the previous increase of 14,492 in the 17-34 age band almost completely “wiped out”.

And it manages to make a small dent in the age level, but nothing that recovers what the FTA refer to as the “sudden exodus” seen after 2016.

The only thing that had really changed was the availability of one of the resources the government had identified as driving the recovery:

European immigration.

European immigration.

After just three years the driver shortage hit crisis levels again. Going from 60,000 to 35,000, and then back up to 59,000 after a reversal that began between 2016 and 2017.

Either it was Brexit, an unidentified economic force, or the free market just stopped working and went to sleep for 4 years, but the industry indicators really just point to one thing.

And not just the vote, because the Brexit deal friction added another pay cut to drivers being paid based on their mileage, regardless of where they came from.

So, not only did Brexit take the opposite position on immigration that the US policy to solve their driver shortage, its trade policy introduced a new problem the US would like to overcome.

Yes, the industry had problems, but it didn’t see those problens as fundamental to solving the driver shortage in 2016, so it would be better to understand what specifically took the driver shortage back into its crisis levels after 2016.

/End

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh