It’s one thing for an insurer to DENY a claim. But why do so many insurers expend such effort to DELAY payment, even for justified claims they know they have to pay?

If you didn’t know already, let me teach you about “float.”

(thread)

If you didn’t know already, let me teach you about “float.”

(thread)

https://twitter.com/acepsteve/status/1445398181894934528

Ten years ago, I was a pediatric nephrology fellow.

One of the the most tedious parts of my job was working on insurance denials.

We’d prescribe an expensive but clearly indicated/necessary medication - say, ESAs or growth hormone for kids with CKD - and it would be denied.

One of the the most tedious parts of my job was working on insurance denials.

We’d prescribe an expensive but clearly indicated/necessary medication - say, ESAs or growth hormone for kids with CKD - and it would be denied.

So I’d call the company.

I’d work my way through the computerized phone tree.

Then I’d talk to a representative.

The representative would nice me up; make me recite policy numbers they already had; maybe ask for a new a lab value or two.

Then the medication would be approved.

I’d work my way through the computerized phone tree.

Then I’d talk to a representative.

The representative would nice me up; make me recite policy numbers they already had; maybe ask for a new a lab value or two.

Then the medication would be approved.

I also spent a lot of time on hold, which gave me time to think.

I wondered: why do they do this?

Was it *really* cost effective?

How much did it cost them to have their representatives staff the phone and nice me up?

Wasn’t that wasted money if they had to pay the claim?

I wondered: why do they do this?

Was it *really* cost effective?

How much did it cost them to have their representatives staff the phone and nice me up?

Wasn’t that wasted money if they had to pay the claim?

After all, the meds we were fighting over were clearly indicated. No pediatric nephrologist is going to back down after a denial of, say, Epogen and just let their patients become transfusion-dependent or die.

If they know they have to pay eventually, why not pay immediately?

If they know they have to pay eventually, why not pay immediately?

Part of the answer is obvious.

Some delayed approvals won’t ultimately have to be paid. Maybe the insured will lose or change their insurance. Or maybe they’ll die.

But part of the answer is less obvious - and more insidious.

Some delayed approvals won’t ultimately have to be paid. Maybe the insured will lose or change their insurance. Or maybe they’ll die.

But part of the answer is less obvious - and more insidious.

When you pay your insurance premium, that money doesn’t just sit around idly, waiting to be forked out the minute you make a claim.

It’s invested in interest-bearing accounts.

And the longer it sits in those accounts, the more interest it generates.

This is the “float.”

It’s invested in interest-bearing accounts.

And the longer it sits in those accounts, the more interest it generates.

This is the “float.”

When you pay your insurance premium, you’re essentially giving your insurer a zero-interest loan.

And a corporation with hundreds of millions of dollars of “floated” cash can create serious revenue when they systematically hang onto those dollars for even a little bit longer.

And a corporation with hundreds of millions of dollars of “floated” cash can create serious revenue when they systematically hang onto those dollars for even a little bit longer.

For instance, Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway has long used this technique to great success:

wsj.com/articles/SB100…

wsj.com/articles/SB100…

Bottom line:

These delays in payment shouldn’t surprise anyone.

It’s all part of the grand financial cat-and-mouse game that our health care system has become.

These delays in payment shouldn’t surprise anyone.

It’s all part of the grand financial cat-and-mouse game that our health care system has become.

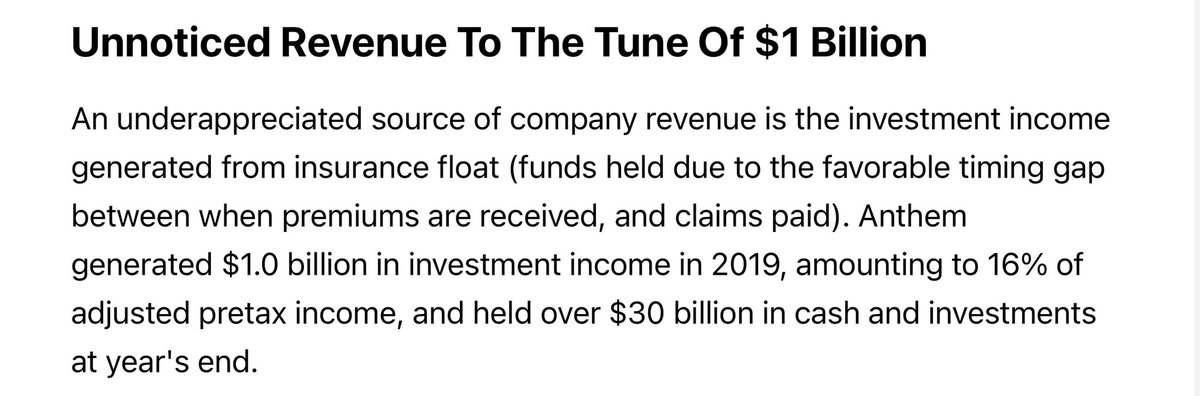

An addendum for those DM’ing me to say this is untrue, the math doesn’t work out, prior auths are *only* to prevent insurance fraud, etc.

Some real numbers, from Anthem in 2019.

16% of their revenue came from investment income… $1 billion total.

seekingalpha.com/article/432364…

Some real numbers, from Anthem in 2019.

16% of their revenue came from investment income… $1 billion total.

seekingalpha.com/article/432364…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh