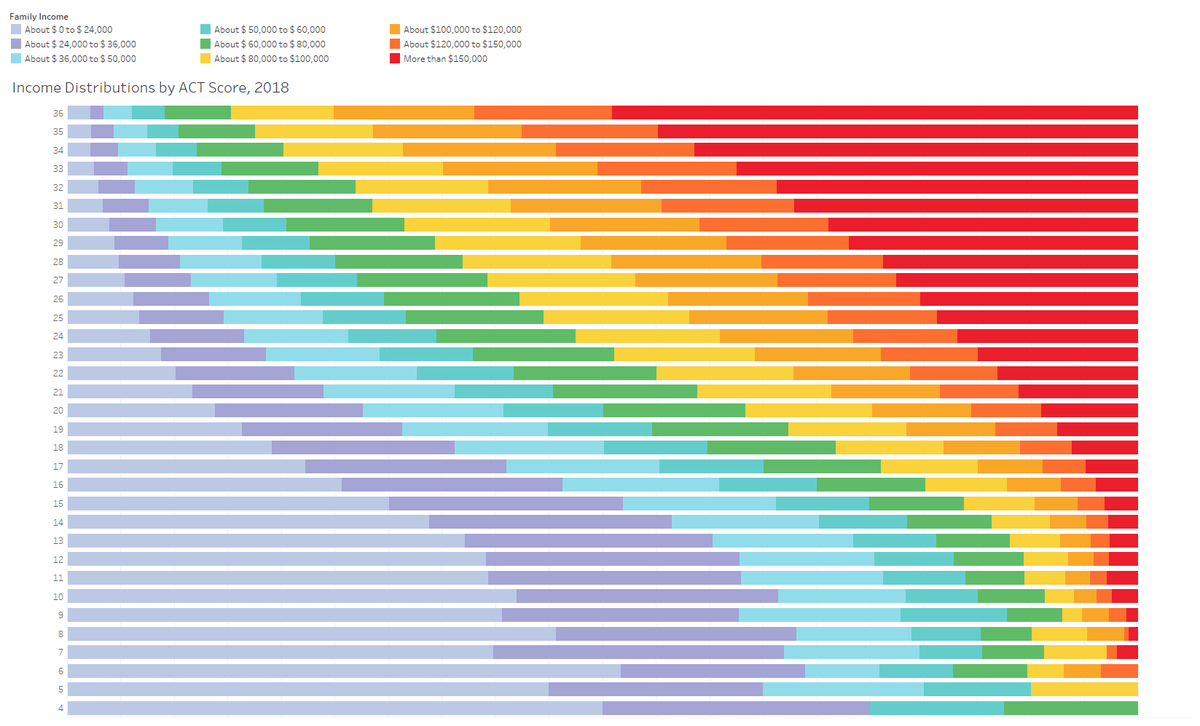

Thread: A slow weekend turned interesting when a student at Columbia, in response to a tweet suggesting the SAT and ACT were "good, actually" posted this chart.

It's a chart I've used several times before, and I explain the way I got the data (I even told people at ACT how I got the data from the tool they provide colleges), and I explain how to read it on a long post here. jonboeckenstedt.net/2020/01/10/som…

The responses are typical, of course, and offer nothing new by way of explanation. My favorite is always that the data make sense because "wealthy people are smarter."

Of course.

Of course.

But for as long as I've been doing this, and for as long as I've looked at the ACT and SAT, something about my point has seemed odd to me. It's like the IKEA desk you assemble and find you have some pieces left over at the end. It was always in the back of my mind.

And then during discussions at the UC Board of Regents meeting, comments by @rothstein_jesse and Lark Park made everything come together: I'd been swayed by the arguments of College Board and ACT into thinking that admissions was just a prediction function.

I knew better.

I knew better.

In fact, at one of my first conferences as a young admissions officer, I listened to a DOA at one of the largest public universities in America say they only admitted applicants with predicted GPAs of 2.8 and above.

I asked him what the mean freshman GPA was.

He said 2.9.

I asked him what the mean freshman GPA was.

He said 2.9.

So I knew, but I sort of got lost there.

Here's the deal: If you use tests where one group always comes out on top based on their opportunity, you're going to select people who are likely to come out on top based on their birth.

That probably suits some people just fine.

Here's the deal: If you use tests where one group always comes out on top based on their opportunity, you're going to select people who are likely to come out on top based on their birth.

That probably suits some people just fine.

But is that what education should do? Just sort people into classes based on their level of opportunity and then perpetuate that level of opportunity?

I don't think so. But that's just me.

I don't think so. But that's just me.

Perhaps my favorite blog post of all time is this one, where I show the ramp up in educational attainment since 1940, and suggest that America's post WWII economic expansion was directly tied to it highereddatastories.com/2019/08/change…

What changed after WWII was the GI Bill that made it possible for many people who were not destined to go to college to get that opportunity. And they didn't all go to the Ivy League, of course.

College made the difference. And I think it could again.

College made the difference. And I think it could again.

So, I picked up a lot of followers over the weekend based on that student's tweet and friends alerting me to it. Glad to have you on board.

The link in my pinned tweet will tell you what you're in for. Come for the higher ed, stay for the IPA bashing.

The link in my pinned tweet will tell you what you're in for. Come for the higher ed, stay for the IPA bashing.

Oh, and #EMTalk

OK, everyone. Thanks (I think) for the discussion, but I'm muting this one, so I won't see any more replies.

I'm gratified that this was so well received, and, as always, puzzled by the misinformation that props up some other "opinions."

Good night!

I'm gratified that this was so well received, and, as always, puzzled by the misinformation that props up some other "opinions."

Good night!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh