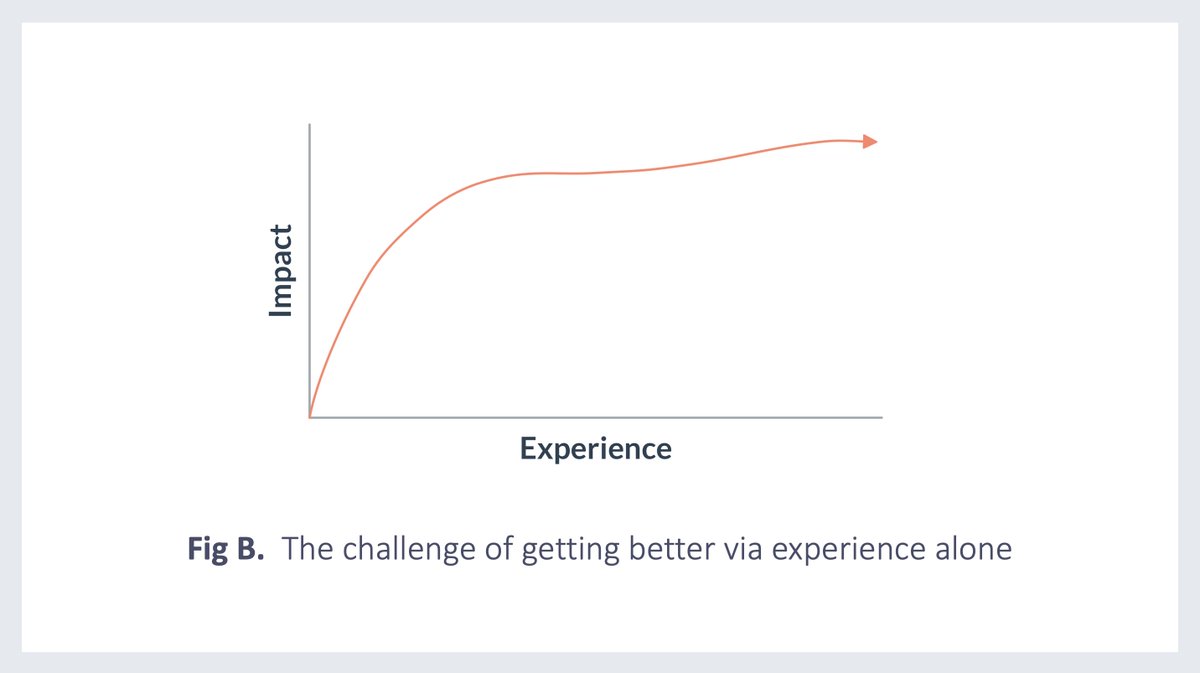

Routines offer serious value for learning.

However, they take time and effort to establish, and often come with an initial dip in performance. During this phase, it can be tempting to give up.

→ This is what @JamesClear calls the 'Valley of Latent Potential'.

🧵...

However, they take time and effort to establish, and often come with an initial dip in performance. During this phase, it can be tempting to give up.

→ This is what @JamesClear calls the 'Valley of Latent Potential'.

🧵...

At their best, routines can:

→ Redeploy attention

→ Reduce behaviour management

→ Increase student motivation, confidence and safety

→ Free up of teacher mental capacity to monitor learning and be more responsive

→ Redeploy attention

→ Reduce behaviour management

→ Increase student motivation, confidence and safety

→ Free up of teacher mental capacity to monitor learning and be more responsive

https://twitter.com/PepsMccrea/status/1411746645348397060

However, these benefits only come once routines become automated.

The amount of time it takes for a routine to automate depends on its complexity and how frequently we run it. Simple routines can take 20 repetitions. More complex ones can take up to 200.

The amount of time it takes for a routine to automate depends on its complexity and how frequently we run it. Simple routines can take 20 repetitions. More complex ones can take up to 200.

https://twitter.com/PepsMccrea/status/140160858865374413

5

During this automating phase, routines require higher levels of energy to maintain, and their 'actual' value often falls short of their 'anticipation' value. Routines can feel like they are a waste of effort.

However, this effort is not being wasted, it is being stored.🔋

However, this effort is not being wasted, it is being stored.🔋

If you play the long game and stick with it, you will eventually reach a tipping point where the benefits begin to outweigh the investment. From then on, your routine will pay back handsomely.

You will have crossed the Valley of Latent Potential.

You will have crossed the Valley of Latent Potential.

Obvious caveat: automating a rubbish routine won't bring you value for learning.

Nuance: sometimes it's important to give up.

Another tricky professional judgment call. Another reason why teaching is hard.

Nuance: sometimes it's important to give up.

Another tricky professional judgment call. Another reason why teaching is hard.

Big thanks to @JamesClear for the 'Valley' and his clear thinking in general. If you haven't read 📚Atomic Habits yet, you're missing out.

NOTE: Some of the original terminology has been adapted to better suit an educational context.

NOTE: Some of the original terminology has been adapted to better suit an educational context.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh