Since covid-19, we are often told that austerity is a thing of the past and that countries will use public spending for a just recovery

Is this actually likely? No: austerity in store for 83 countries

✅New open access article w @thomstubbs

doi.org/10.1111/1758-5…

Short thread

Is this actually likely? No: austerity in store for 83 countries

✅New open access article w @thomstubbs

doi.org/10.1111/1758-5…

Short thread

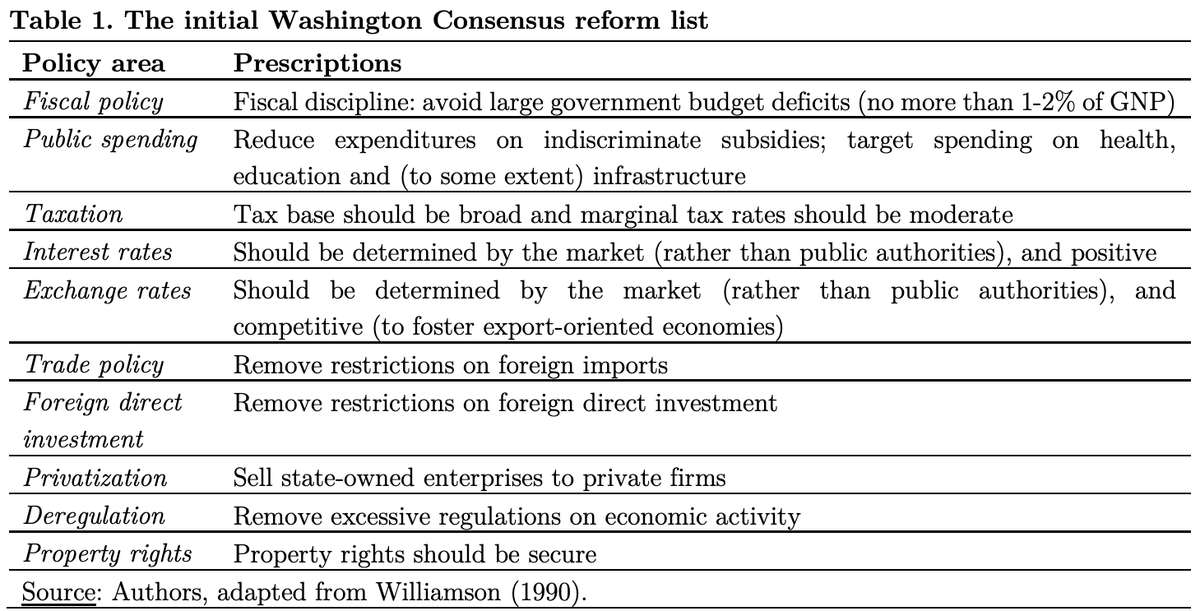

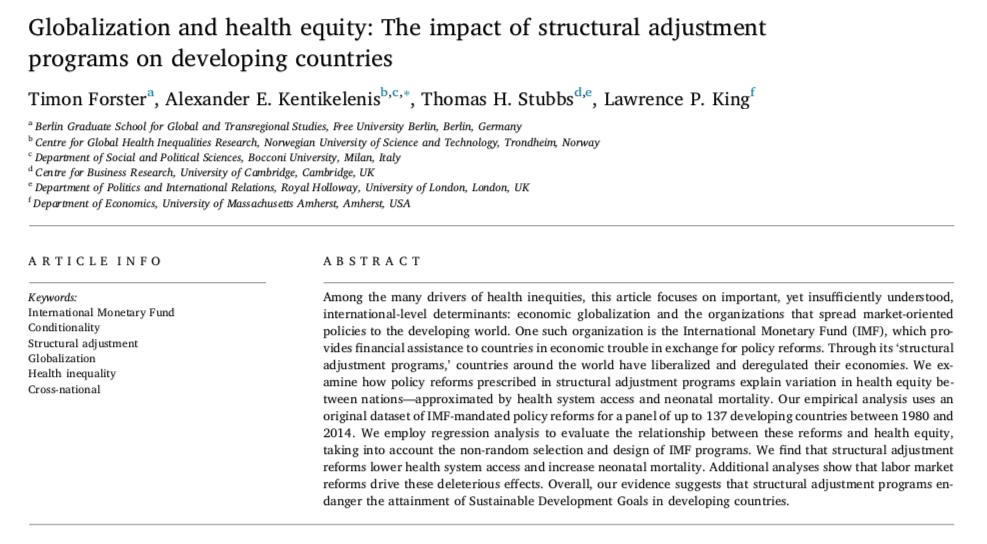

According to luminaries of global economic governance, fiscal policy will not be the same in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Even Carmen Reinhardt has turned austerity-skeptic.

Even Carmen Reinhardt has turned austerity-skeptic.

Some, like @MESandbu of the FT, think that there is now a 'New Washington Consensus':

"fiscal probity is no longer about reining in public spending but about getting value for money – and spending more where the value can be found"

ft.com/content/3d8d22…

"fiscal probity is no longer about reining in public spending but about getting value for money – and spending more where the value can be found"

ft.com/content/3d8d22…

But is this time really different, and is austerity a thing of the past?

We looked at the IMF's public spending projections, and compared them to the average of the 2010-19 period.

Two headline findings:

We looked at the IMF's public spending projections, and compared them to the average of the 2010-19 period.

Two headline findings:

Rich countries will gradually phase out covid-related spending increases: by 2023, they will be still spending more than the 2010s

Middle income countries are expected to rapidly scale back *below* 2010s avg

Poor countries will soon revert to their very low spending levels

Middle income countries are expected to rapidly scale back *below* 2010s avg

Poor countries will soon revert to their very low spending levels

83 countries will still face aggressive austerity in the near term: by 2023, their public spending in 2023 will be at least 1 percentage point less than the 2010s avg.

This heavily limits ability to pursue a 'just recovery' (let alone a green and inclusive transition)

This heavily limits ability to pursue a 'just recovery' (let alone a green and inclusive transition)

Overall, austerity will expose 2.3bn to budget cuts.

What does this mean for countries in crisis, and for the future of global public health?

Read the paper! Open access too. ✅

doi.org/10.1111/1758-5…

What does this mean for countries in crisis, and for the future of global public health?

Read the paper! Open access too. ✅

doi.org/10.1111/1758-5…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh