The Siege of Dorostolon was the savage conclusion to the Rus-Byzantine struggle over the wealthy lands of the now broken Bulgarian Tsardom.

Sviatoslav’s army had been reduced from 60,000 to 30,000 men. No longer able to dictate the course of the campaign, stinging from the loss of Pereyaslavets, and the departure of his now unaffordable Pecheneg mercenaries, Sviatoslav reorganized at the impressive fortress.

Tzimiskes arrived at the fortress with an army of equivalent strength. (15,000 infantry & 13,000 cavalry) Sviatoslav gave battle on a field 12 miles from the fortress, Rus and Byzantine infantry traded blows into the evening. The Cataphracts charged & won a costly victory.

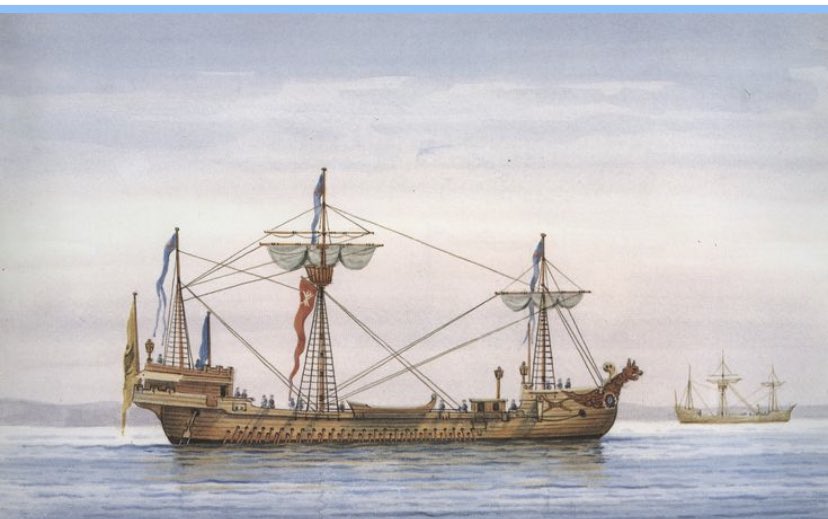

The Rus shield wall broke and many were cut down in the pursuit, but most reached safety. Unable to break the Rus in open battle, Tzimiskes settled in for a siege. A Byzantine flotilla of 300 ships, equipped with Greek Fire, sailed down the Danube and completed the encirclement.

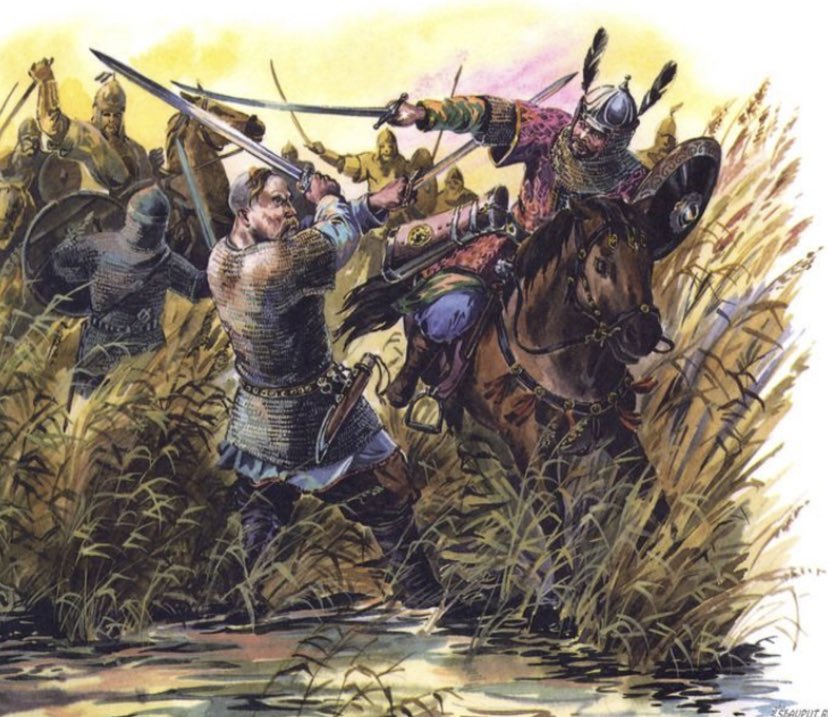

Feeling the effects of starvation, the Rus had to act, and a series of bloody engagements unfolded on the fields surrounding the fortress. The fighting was fierce as the Byzantines sought to break Sviatoslav below the walls and the Rus tried to claw their way to safety.

Desperate to regain the support of their gods, the Rus drowned children and prisoners in the Danube. This did not improve their situation. At one point in the siege a group of 2,000 Rus warriors successfully slipped past the Byzantine naval blockade in their monoxylon.

After finding food and supplies the Rus returned to Dorostolon. On the way back they chanced upon some Byzantine cavalry watering their horses and ambushed them, killing many. The Rus were buoyed by this small victory and Tzimiskes was livid with his soldiers for their laziness.

The fighting claimed Tzimiskes’s relative, Ionnes Kourkouas. The Rus hung his severed head from the walls. Anemas, son of the recently conquered Cretan Emir, returned the favor. When a Rus detachment sallied from the fortress Anemas cut down Ikmor, the Rus second-in-command.

Byzantine sources claim Ikmor assassinated Anemas’s father during the siege of Chandax, where he served as a mercenary. Apocryphal or not, the tale demonstrates the already deep connections between the Rus and Byzantine worlds in the 10th century.

The next day Sviatoslav led an assault at sunset, hoping to overwhelm the Byzantines and make a break for safety. Anemas rode forth and slashed Sviatoslav on the neck. Sviatoslav was thrown from his horse by the powerful sword-stroke, his armor saved his life.

The Druzhina came to the aid of their king and swarmed Anemas. Anemas killed several of Sviatoslav’s elite warriors before falling under a hail of axes and swords. The Rus then continued with their attack but were repulsed with heavy losses.

Sviatoslav’s army was broken, starving, bloodied, and surrounded. After 65 days of fighting, Sviatoslav met with Tzimiskes to discuss the terms of his surrender. Leo the Deacon was present for the meeting between the legendary leaders and wrote down his recollections.

Sviatoslav rowed to the meeting in a monoxyla with his retinue. He wore the same white clothes as them, although his were cleaner. The only clue to his rank was the large gold earring studded with a gem and two pearls.

Leo remembered Sviatoslav as a blue-eyed man of average height and muscular build. Sviatoslav had a wispy beard, large mustache, and a bald head save a long lock on the side of his head. The terms of Sviatoslav’s surrender were lenient considering his dire circumstances.

Sviatoslav renounced his claims on the Balkans and Southern Crimea, agreeing to stay west of the Dnieper River. In return, Tzimiskes provided food and supplies to the Rus. Sviatoslav blamed his failure on the Pechenegs who abandoned him as his campaign unraveled.

After Sviatoslav withdrew, his army wintered on Berezen Island at the mouth of the Dnieper. Conditions were bleak and famine stalked his warriors. Fearing the ambitious Sviatoslav would break this treaty too, Tzimiskes suggested the Pecheneg khan Kurya attack him at the rapids.

Sviatoslav, ignoring the warnings of warlord, Sveneld, pushed to the Dnieper Rapids in early 972. Kurya fell on the weakened Rus and Sviatoslav was killed with many of his remaining warriors. The Primary Chronicle says that Kurya made Sviatoslav’s skull into a chalice.

Sviatoslav’s early death and disaster in the Balkans marred his legacy. Although his conquests broke the arch rival of the Rus, the Khazars, most of his best warriors died in the Balkans or on the Dnieper. The regencies he set up for his three young sons also led to trouble.

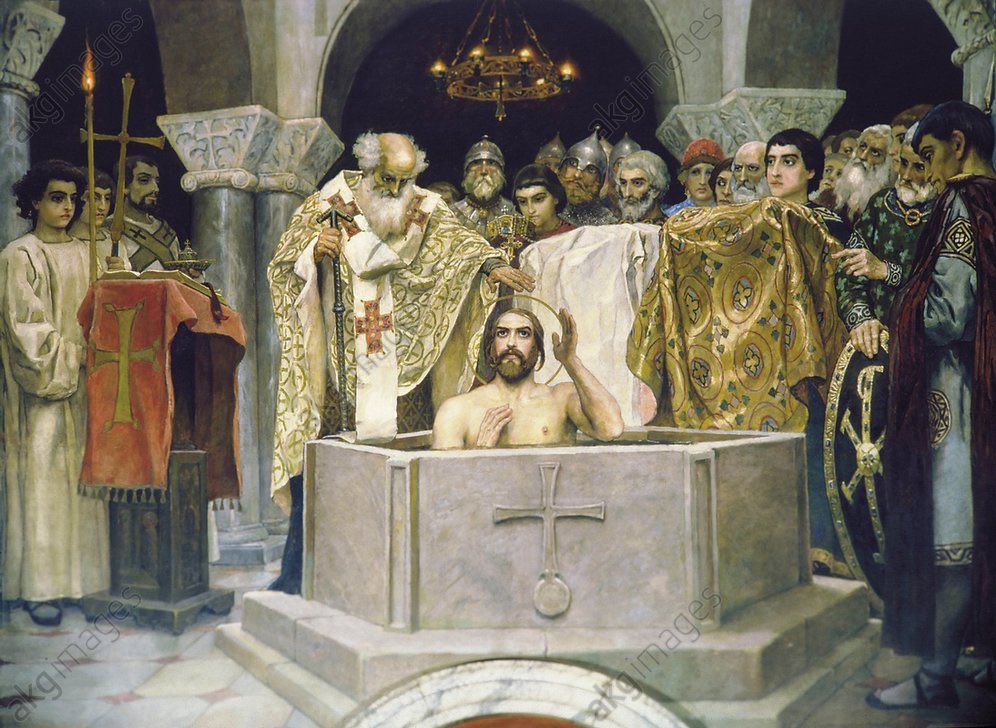

The fractured political landscape of the Rus after Sviatoslav’s death would lead to devastating civil war and only with the victory of Vladimir the Great would the Rus once again return to the world stage.

Our last thread on the Rus will cover the civil wars of Sviatoslav’s sons and the rise of Vladimir, godfather of the Varangian Guard.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh