Thread: New England, Crimea. How Anglo-Saxon migration transformed Byzantium and created the first English colony.

955 years ago today, William of Normandy defeated Harold Godwinson’s army at Hastings and became the King of England. William’s regime was slow to eliminate Anglo-Saxon influence in England, but Anglo-Saxon uprisings in the north of the country drew his wrath.

Over the winter of 1069-1070 William prosecuted the “Harrying of the North,” killing his way through Northumbria. Records from the Domesday Book estimate 75% of the population fled or was killed. The last Æthling, Edgar, submitted to William in 1074, making his rule uncontested.

Dispossessed nobles and Anglo-Saxon refugees unwilling to bow to William’s new regime began seeking a new home, “The English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off that what was so intolerable and unaccustomed.”

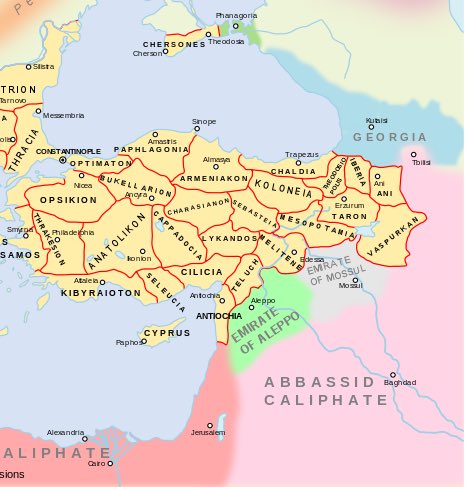

Sources mention that a fleet of between 235 and 350 ships set off from England and into the Mediterranean in 1074. While in Sardinia or Sicily, they received word that Constantinople was under attack. The leaders of the fleet came to the relief of the city and defeated the Turks.

The Emperor, Michael VII, was grateful and “offered them to abide there and guard his body as was wont of the Varangians who went into his pay.” 4,350 of the English took up the Emperor’s offer, but most “begged the king to give them some towns or cities which they might own.”

Michael VII offered them rule over Crimea which had recently been overrun by steppe tribes from the north. After many battles the English secured this new homeland. They named it Nova Anglia, building cities and towns, two of the most prominent being named London and York.

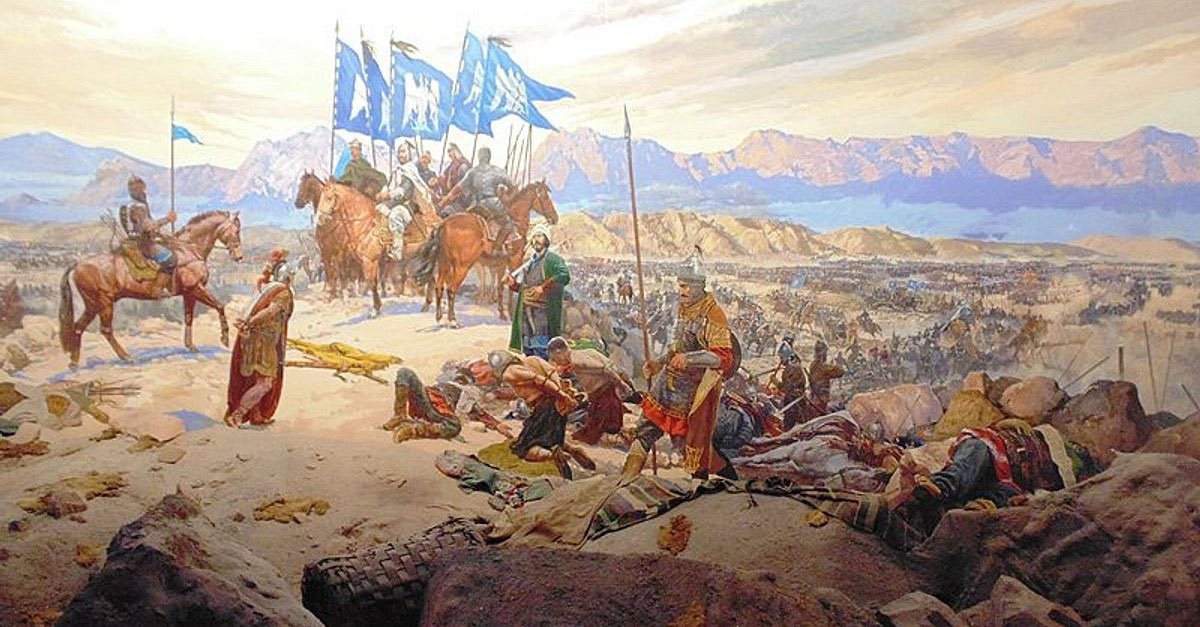

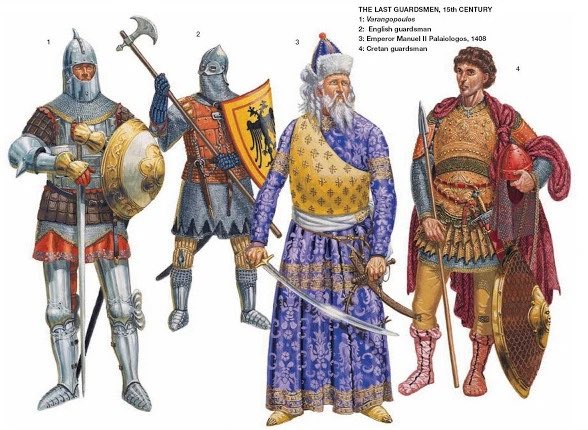

The Varangian Guard had been devastated at the Battle of Manzikert several years before and the influx of thousands of Anglo-Saxon warriors permanently changed its character from largely Slavic and Nordic to Saxon.

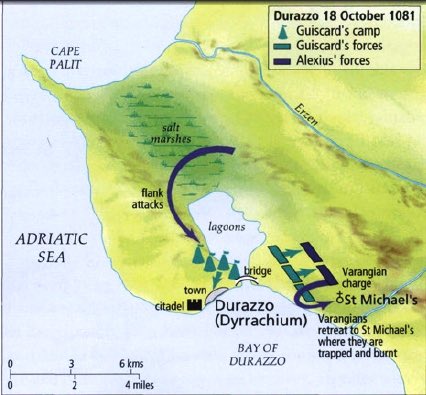

Contemporary sources began to use the word Englinbarrangoi (Anglo-Varangians) to describe them. This revamped force played a prominent role in the Battle of Dyrrhachium in 1081.

The hated Normans had invaded the Balkans and were besieging the fortress of Dyrrhachium. Emperor Alexios I Komnenos led an army to relieve the city. The Varangians were deployed in front of the main army, absorbing many Norman cavalry charges.

The outnumbered Varangians broke the Norman right flank and pursued their bitter foes to the sea. In a repeat of Hastings, they became separated from the main army and were flanked. The exhausted Saxons fled to the Church of Saint Michael.

The Normans lit the church on fire and many of the Varangians died fighting or burned in the flames. The Varangians exacted heavy casualties on the Normans, but the Byzantine lines broke and the Normans won the day.

More Anglo-Saxons would flee England for Byzantium in the coming years. Siward Barn, a prominent resistance figure to Norman rule, was freed from prison in 1087 and made his way to Constantinople in 1091. Siward defeated the Turkish pirate, Tzachas, who was attacking the city.

When John II Komnenos failed to break through the Pecheneg wagon-circle at the Battle of Beroia in 1122, he reluctantly committed his precious ‘wine-skins,’ the heavy-drinking Varangians. The ax-wielding Varangians hacked their way in and slaughtered the Pechenegs.

The Varangian Guard were among the most stalwart defenders of Constantinople during the siege of 1204, retaking sections of the sea walls overrun by the Venetians. When the Crusaders took the city, the Varangians were the last to lay down their arms.

The Varangians survived the fall of the city and detachments existed in the Desporate of Epirus and the Empire of Nicea. The Varangians were present with Michael VII when he recapture Constantinople in 1261.

The Varangians in Byzantine service retained their English culture, language, and Catholic faith. The Guardsmen built the Church of St. Nicholas and St. Augustine of Canterbury, now known as Bogdan Serai, and staffed it with Hungarian Catholic priests.

Varangians in the 14th c. retained their Christmas tradition of wishing the emperor a long life in English. In 1404, Byzantine envoys to Rome mention “Axe-bearing soldiers of the British race,” in Constantinople, serving the emperor. This is the last mention of the Varangians.

The continued Anglo-Saxon character of the Varangians can be explained by the continued survival of English Crimea within Byzantium’s political orbit. Warriors would come to seek employment in service of the emperor every generation, reinforcing its Englishness.

We have contemporary sources supporting this survival. In 1246, Pope Innocent IV sent Franciscan friars on a mission to the Mongols. The friars wrote of the “Saxi” people of Crimea who resisted the Tartars in fortified towns.

We also have maps of Crimea from the 14th-16th centuries that bear cities with names like “Londina” and “Porto di Susacho” (Port of Sussex).

By the end of the Medieval Period, conquest and assimilation would begin to erode the Anglo-Saxon character of the English Crimeans. However, they may have integrated with the Crimean Goths, influencing the language and possibly speaking it until 1945.

Although we have no records to prove it, it is likely the Varangians served the emperor faithfully until the end in 1453 and fell around Constantine XI, “loyal from the days of old to the Emperor of the Romans.”

This thread only scratched the surface of the fascinating history of Anglo-Saxons in the Byzantine Empire and I plan to make more exploring their history.

Go check out this excellent thread posted a few months ago about Anglo-Saxon Varangians and New England in Crimea.

https://twitter.com/femboy_swift/status/1421473863771299843?s=21

https://twitter.com/femboy_swift/status/1421473863771299843

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh