When Oleg died in 912, he left Igor with a successful state. Lucrative trade flowed up and down the rivers and the Slavic tribes were subdued. We have few sources from the first 30 years of his reign, only an unsuccessful raid down the Caspian Sea is recorded in 913.

It is possible Igor did not rule during that time, or the Rus experienced a period of civil war and instability until Igor solidified control sometime before 940.

By 941, Igor was ready to strike further afield for plunder and trade. The massive raids Rus lords and rulers organized served a dual purpose; they secured massive wealth in loot, ransoms, and protection money, and gave the Rus bargaining power in new trade agreements.

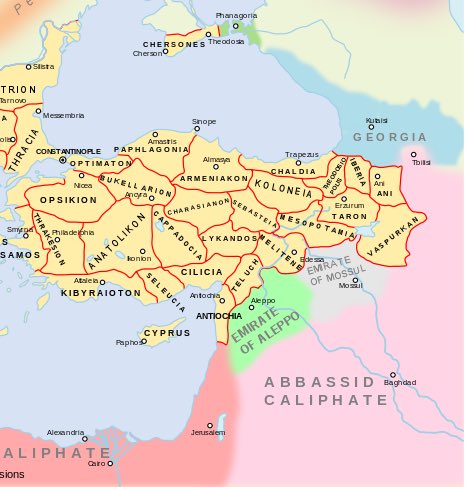

Igor’s first raid major was on Constantinople. Like Oleg before him, he amassed a large fleet and struck when the Imperial Army and Navy were away in the East fighting the Arabs. Rus traders from the St. Mamas colony likely tipped him off that the city was vulnerable.

The Rus disembarked with some Pecheneg allies in Bithynia and began plundering the wealthy region unchallenged. Rumors of atrocities spread; people crucified, others nailed through their heads.

As the Rus closed in on Constantinople, Theophanes, a leading palace official, organized the defense. Liudprand of Cremona related his step-father’s experience of the siege. As 1,000 Rus ships closed in on the capital, Theophanes could only find 15 retired ships to oppose them.

Igor, wanting to capture the ships, attacked. However, Theophanes had outfitted the ships with Greek Fire and “the Rus', seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire.”

This prevented the Rus from seriously pressing Constantinople, but their raid continued as far south as Nicomedia. In September, John Kourkouas and Bardas Phokas returned at the head of the Imperial Army, prompting the Rus to begin pillaging Thrace.

At the close of the campaign season, the Rus made preparations to return to Kiev. However, Theophanes ambushed them with the Imperial Navy, annihilating the force. Few Rus returned to Kiev.

Igor’s next raid was down the Volga and into the Caspian Sea. The Rus attacked Arran, capturing the capital of Bardha’a. The Rus intended to stay and rule much like in Russia. However, conflict broke out with the local people. The Rus were weakened by fighting and dysentery.

The Rus “left by night the fortress in which they had established their quarters, carrying on their backs all they could of their treasure, gems…boys and girls as they wanted, and made for the Kura River, where the ships in which they had issued from their home.”

The Rus returned home with great wealth. This successful raid lead to the Khazars closing Rus access to the Volga. The Khazars, allies of the Byzantines and defenders of the Muslims of the Caspian, jockeyed constantly with the Rus over the lucrative trade routes to the South.

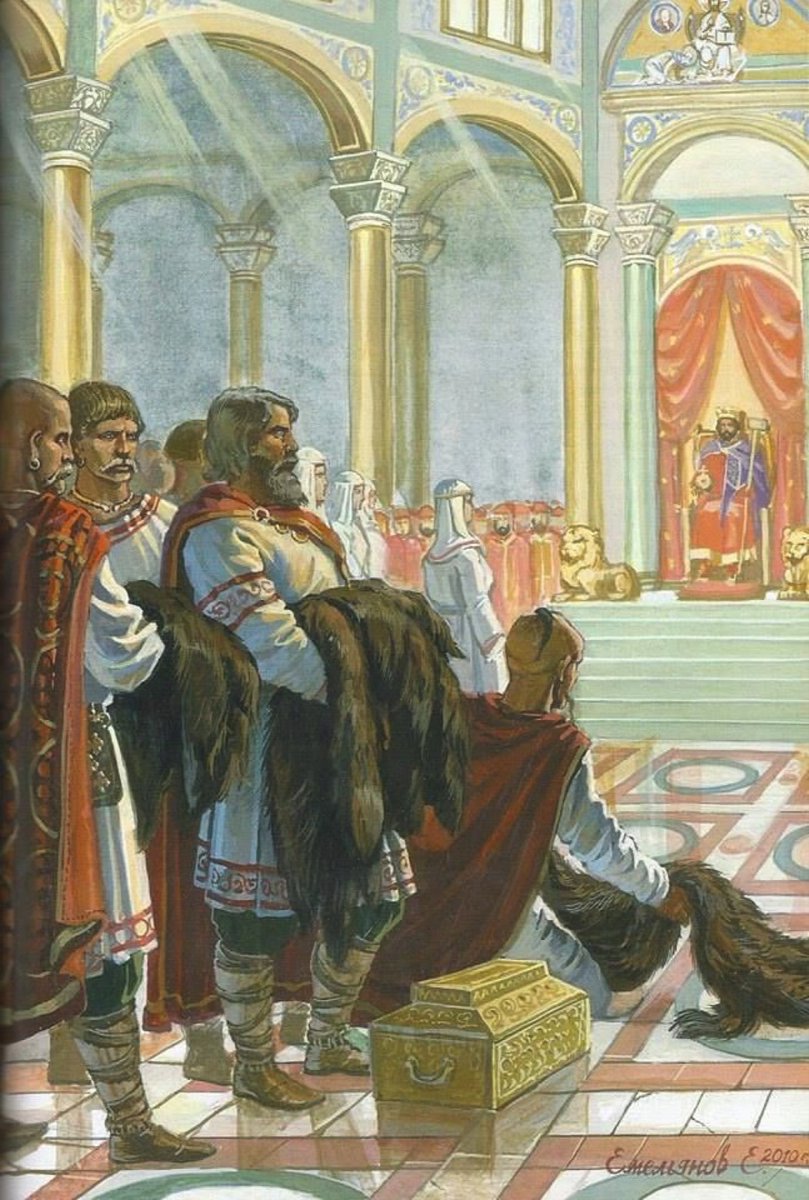

Igor’s final raid returned to Constantinople in 944, larger and prepared to avenge the disaster three years earlier. Instead of fighting off this larger force, the Byzantines negotiated a new treaty with the Rus. Igor accepted despite it being worse than the treaty in 911.

The treaty recognized the joint administration of the mouth of the Dnieper (Rus were not allowed to winter there), the protection of Byzantine fishermen in the Black Sea, the Rus promising not to attack Cherson, and Rus merchants needing to carry charters from the Prince of Kiev.

These charters were to explain the number of ships and people sailing to Constantinople, without which they were liable to be apprehended by Byzantine authorities as raiders. The treaty also reveals social changes occurring within the Kievan Rus.

The Kievan officials, merchants, and nobles swore to uphold the treaty to their pagan gods or Jesus Christ, indicating christianization was underway, at least among the elite. Some signatories also bore Slavic and Finnic names, although the vast majority are still Norse.

Although Igor certainly supported or even commissioned these raids, we have no sources that indicate he personally led the expeditions in 943 or 944, letting powerful warlords command in his stead. Igor may have been busy with unrest in his own lands.

Slavic tribes often chaffed under the harsh rule and tribute payments of their Varangian overlords and rebellions were frequent. In 945, Igor went to the land of the Drevlians outside Kiev to collect the tribute. The Primary Chronicle reports the event.

Igor, in his greed, demanded a second payment in the same month. Enraged, the Drevlians attacked Igor and “bent down two birch trees to the prince's feet and tied them to his legs; then they let the trees straighten again, thus tearing the prince's body apart."

With Igor’s death his widow, Olga, and their 3 year-old son, Sviatoslav, were thrust into a precarious situation. Sandwiched between power-hungry nobles and Slavic rebels, Olga must fight for her survival and that of her son.

Olga’s desperate struggle and ruthlessness to secure her rule is one of my favorite stories in Rus history and will be the subject of the next thread.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh