China's digital manhunt goes global: The final piece in our series on China's outbound propaganda and censorship shows how police use ever more sophisticated tech to find and silence those overseas. They target Chinese students and Chinese Americans alike. nytimes.com/2021/12/31/bus…

For a sense of what that looks like, here's a video of Chinese police harassing a Chinese student living in Australia. They summoned her father in China to the station, called her on his phone, and demanded she delete a Twitter account that mocked Xi Jinping.

One contractor who unmasks critics in the US for security authorities uses open-source investigation tools, databases leaked on the dark web, and other records, like voting and license registries. He has been assigned journalists and Chinese-American policy analysts.

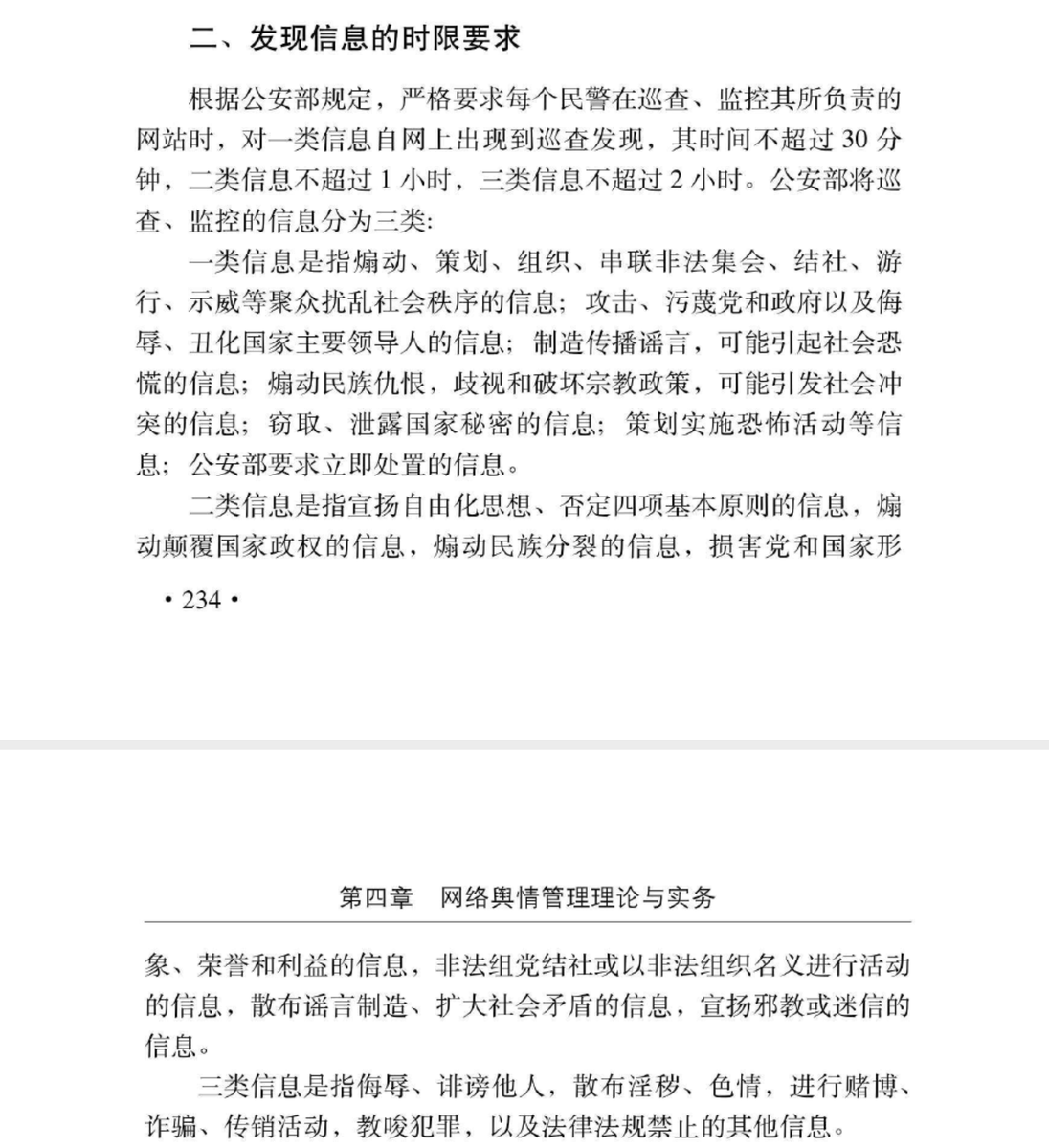

The goal is to find China connections and leverage them to enforce self censorship. His reports label speech on a numerical system 1: criticizing leaders/planning political action 2: broader criticisms that harm China's image and ethnic separatism 3: libel, gambling etc.

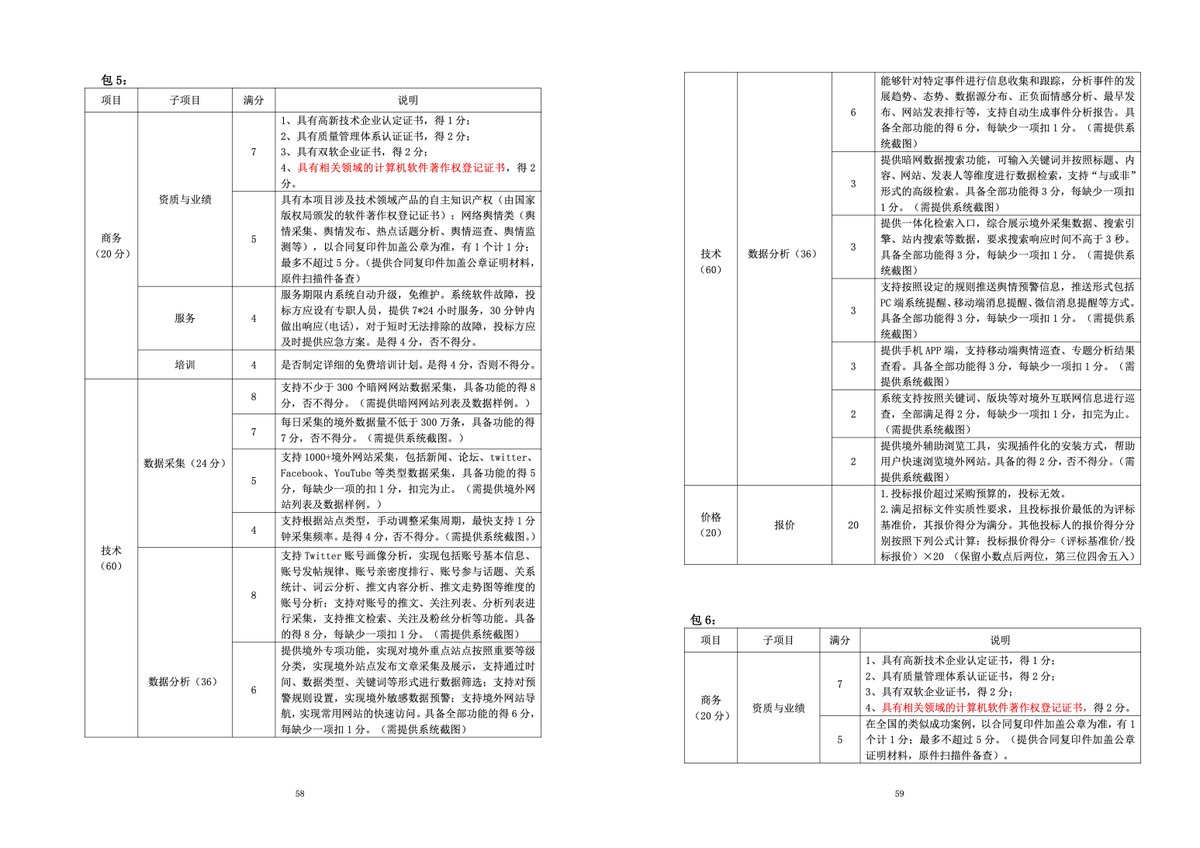

Procurement documents bear out the trend. There are more appearances of police across China spending on the practice. This, from Shanghai police, uses the term “touching the ground” to refer to finding overseas critics and identifying their connections to China.

They have other means too. After the Chinese student in Australia was contacted by police, she left up her account. Yet Twitter took it down, coincidentally on China's National Day. They restored it when we asked, but didn't say why it was removed. My theory is mass reporting.

@YaxueCao told us, the logic is that of an overactive lawn mower: “They cut down the things that look spindly and tall — the most outspoken. Then...the taller pieces of grass no longer cover the lower ones. They say, ‘Oh these are problematic too, let’s mow them down again.’”

That means the digital dragnet and campaign to police speech overseas has targeted increasingly obscure critics. Many Chinese students who have no more than 100s of followers have been contacted. Many are mystified how they were connected to accounts they thought anonymous.

Some Chinese have been incredibly brave in the face of this, one woman told us: “Even though it is still dangerous, I have to move forward step by step...I can’t just keep censoring myself. I have to stop cowering.” Yet many others calculate it's not worth the risk.

This is the punitive side of a sweeping, well-resourced effort to change the tenor of global discussions on China. Increasingly Chinese propaganda campaigns are being blasted out via bots, officials, and state media on platforms like Twitter and Facebook. nytimes.com/interactive/20…

In other cases, authorities set up a reward structure to encourage foreign friends to parrot propaganda talking points. They have successfully seeded a fast-growing group of influencers with money, official and bot amplification, and access. nytimes.com/interactive/20…

As with Peng Shuai, it doesn't always work. Authoritarian propaganda rings hollow on overseas social media. Yet there is every indication China is committed and its strategies are improving. It is already changing the online debates, it will continue to. nytimes.com/interactive/20…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh