Been wondering a lot lately just how valuable ubiquitous dichotomies like developed/developing or developed market (DM) vs emerging market (EM) actually are (esp as they have become a very popular analytical framework in the Covid era).

These terms often conflate many different ideas/metrics, such that they take on different meanings to different people in different contexts. E.g. when we compare DMs to EMs, are we referring to the state of those countries’ financial markets OR their societies? Or both ?

Are these concepts useful for *financial as well as *political* analyses, or are they more useful for one than the other? Some markets may be “emerging” for financial or economic purposes but “developed” in a socio-political sense. Can these terms accommodate that complexity?

For example, I like this (social) definition from a friend of “development” as “progress toward a society that is able to solve problems of human existence and make life more meaningful and more prosperous.”

By this definition, China is developed; it has demonstrated the ability to make life more meaningful and prosperous for a large chunk of its society.

But China is still a middle-income country, with per capita GDP lower than Chile’s. Thus it is still an emerging economy.

But China is still a middle-income country, with per capita GDP lower than Chile’s. Thus it is still an emerging economy.

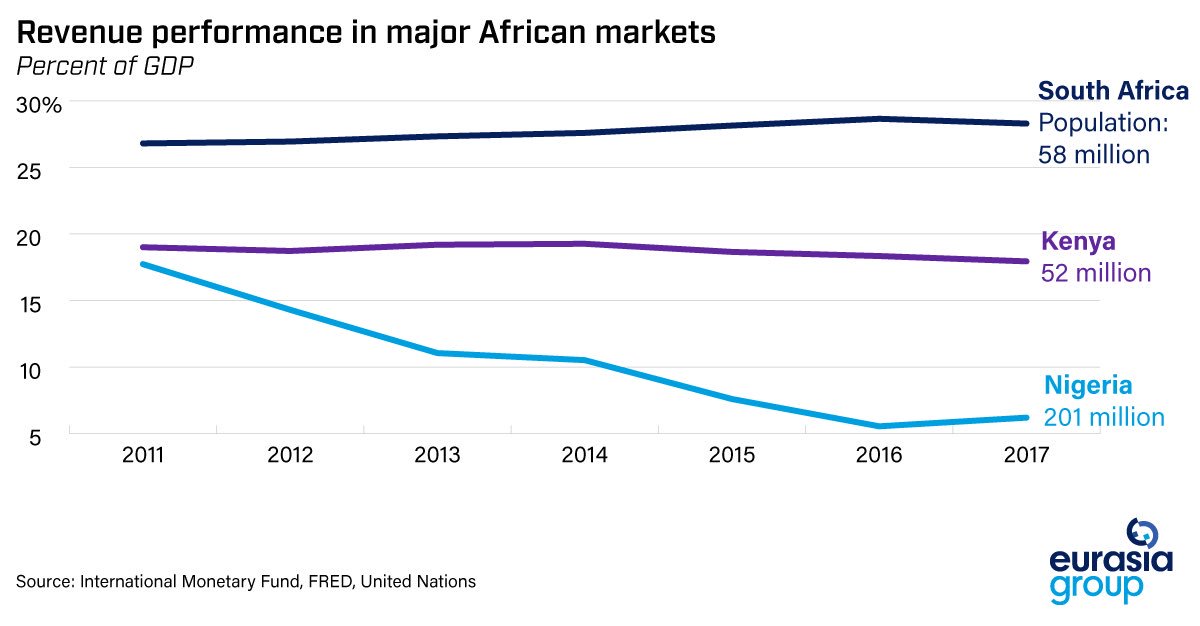

South Africa is also an emerging economy but it arguably has not demonstrated the ability to solve critical societal problems & make lives more prosperous. Do we not lose much of this complexity by always bunching these two countries into a simple “EM” or “developing” category?

Found this thread helpful. Probably best to refer to “most and least” industrialized countries and/or low, middle, and high income countries when referring to economic matters, then also make a clearer analytical distinction b/w economic/financial challenges and societal ones.

https://twitter.com/MssZeeUsman/status/1479810885308854274

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh