For today’s daily dose of women mystics in medieval Islam, we’ll be looking at marriage, sex, and inter-gender relations between pious Sufi men and women. Let’s see what Hasan al-Basri has to say about his religious sessions with the famous woman mystic Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya 🧵~mq

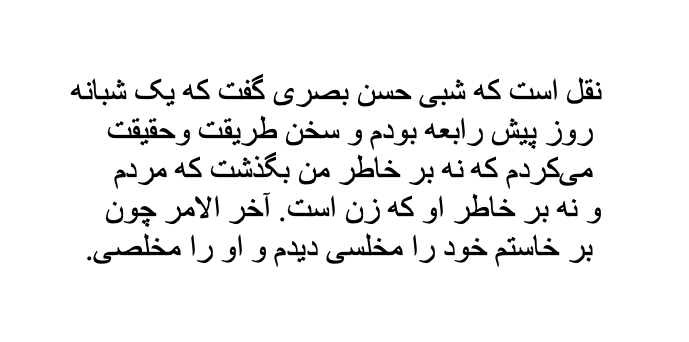

‘I was with Rābi‘a for one full day and night. I was talking about the Path and the Truth in such a way that the thought ‘I am a man’ never crossed my mind, nor did ‘I am a woman’ ever cross hers. In the end when I got up, I considered myself a pauper and her a devotee.’

It is often posited that Sufi women lacked access to all-male religious spaces because of anxieties over interactions between genders. But to what extent is that really true?

The idea that Sufi men and women could not always interact freely is certainly supported by the source material. However, our biographers are often able to circumvent concerns over mixed-gender spaces. The key is that the women, in particular, must be seen as genderless.

Once that happens, we find evidence of permissible or beneficial contact between the genders. Ibn al-Jawzī also includes one such tale, related by Dhū al-Nūn, as he listens to a woman praying in the Ka‘ba, momentarily forgetting the distinction between the sexes (tr. Lewisohn):

By transcending the body and its desires, Rābi‘a and other female saints are able to interact more freely with men, attend mixed gatherings with them, and function as either masters or disciples.

At the same time, pious women like Rābi’a were aware that marriage could represent a threat to their ability to worship freely, or even to their perceived status in the religious community. To a marriage request from Ḥasan al-Baṣrī, Rābi'a responded:

‘Matrimony is predicated upon existence. Here, existence has vanished and I have become nothing. Being is through Him, and I am made up entirely of Him. I am in the shadow of His command. The marriage request must be made of Him, not of me.’

(tr. Losensky)

(tr. Losensky)

Again, corporeal existence must be negated for mystics of opposite genders to interact without reserve.

Not all women mystics were able to remain unmarried, however. To reconcile the perceived conflict between her duty to God and her duty to her husband, the female saint is valorised for her apparent ability to compartmentalise her commitments.

In the case of the wife of Aḥmad b. Abī al-Ḥawārī, there are reports from her husband describing her dedication to celibacy:

"She said to me: ‘It is not lawful for me to forbid you from myself or to forbid you from another. Go ahead and get married to another woman.’ So I married three times. She would feed me meat and say: ‘Go with strength to your wives!’ [...]

"If I wanted to have sex with her during the day, she would say: ‘I implore you in the name of God to not make me break my fast today.’ And if I wanted her during the night, she would say: ‘I implore you in the name of God to grant me this night for God’s sake.’"

We see what you did there, girl😉 The conflict of expectations placed on the Sufi wife–both to serve her husband and to serve God by her ascetic practice–come to a head here. By satisfying both requirements, but putting the Lord above her husband, she acquits herself nicely.

There’s a lottttt more I could say about this but we’ll leave it there for now. Join me tomorrow for more details on the biographers themselves as they tackle that all-important question: why should we be writing women’s histories at all?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh