One of my favourite papers of 2021: "The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations" by @AndrewLFanning, @DrDanONeill, @jasonhickel, and Nicolas Roux.

🧵

🧵

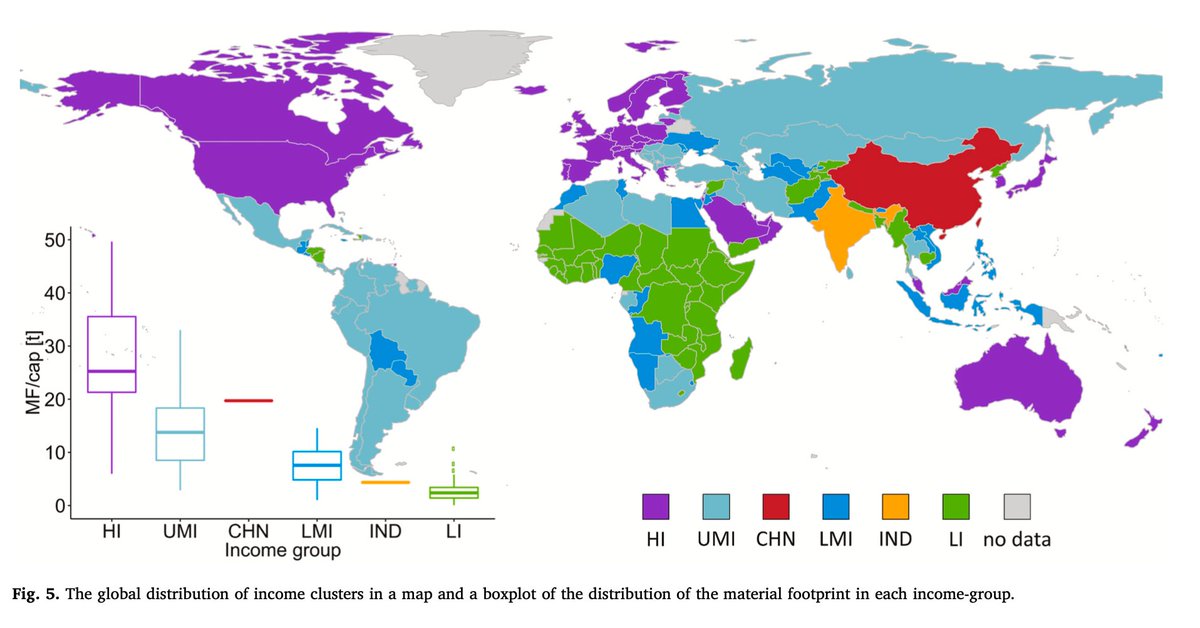

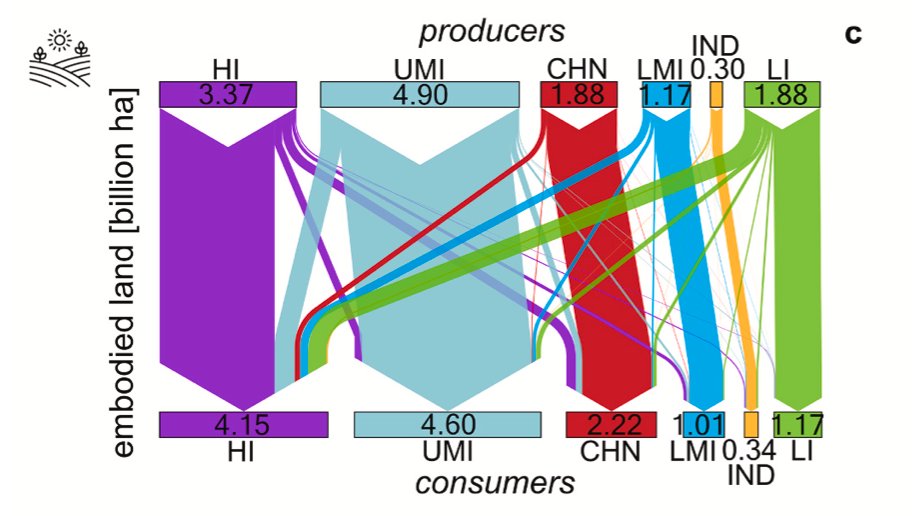

The paper looks at 11 social and 6 environmental indicators for 140 countries between 1992 and 2015. It also models 'business-as-usual' projections up to 2050.

This donut-shaped figure shows which ecological boundaries are transgressed: the 'OVERSHOOT' (the red bits outward), and which social foundations are unreached: the 'SHORTFALL" (the red bits inward).

Findings: countries who reach their social foundations overshoot their ecological boundaries; and countries who do not overshoot them usually shortfall their social indicators.

Here is the main figure: it shows (on the left) that countries who reduce their shortfalls usually increase their footprint. It also shows (on the right) that countries achieve similar levels of social performance at varying levels of resource use.

Costa Rica is interesting outlier: it manages to increase its social performance without too much environmental pressures. One could say that, the 'ecological intensity of its wellbeing' is relatively low.

Now here comes to the projection to 2050. Following a business-as-usual scenario, there will be less social shortfalls in 2050 but more countries will have transgressed their ecological boundaries.

Here is how it looks for Germany, China, and Nepal, three countries with radically different challenges: degrowth, selective (de)growth, and green growth.

In order for countries in social shortfalls to be able to increase their resource use, high-income countries must lower their footprints, which implies a reduction of their production and consumption. #degrowth

Unlike the (dull and narrow) literature that looks at the decoupling of GDP and carbon, this paper offers a new way to think about sustainability: What is the most ecologically efficient way to secure wellbeing?

End thread/

nature.com/articles/s4189…

End thread/

nature.com/articles/s4189…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh