Here is an indispensable piece of work to understand the global dynamics of environmental pressures. Thomas Wiedmann & Manfred Lenzen in @NatureGeosci.

🧵

🧵

In a globalised economy, many processes of production scatter through complex, international supply chains. To calculate the footprint of one single country, one must keep track of all the impacts its consumption has abroad.

This article is a review of the empirical literature that has looked at the environmental and social impacts embodied in international trade.

I often hear that high-income countries have clean air because of technology and environmental awareness. In fact, they do mostly because they outsource their most pollutive productions abroad.

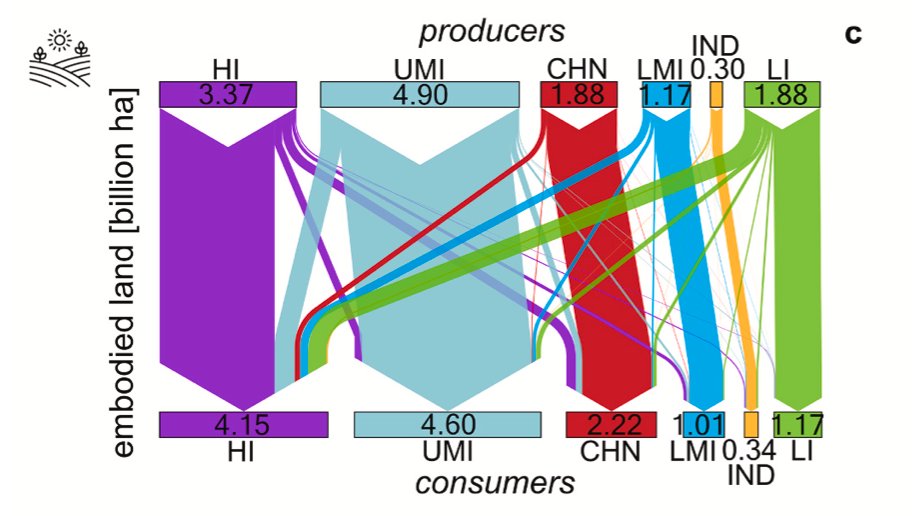

This pattern repeats itself for other environmental impacts. For example, 50% of the biodiversity footprint of developed economies happens outside of their borders.

If it looks like the EU has a sustainable use of water, it's because 80% of the water scarcity situations its consumption creates happen in other countries.

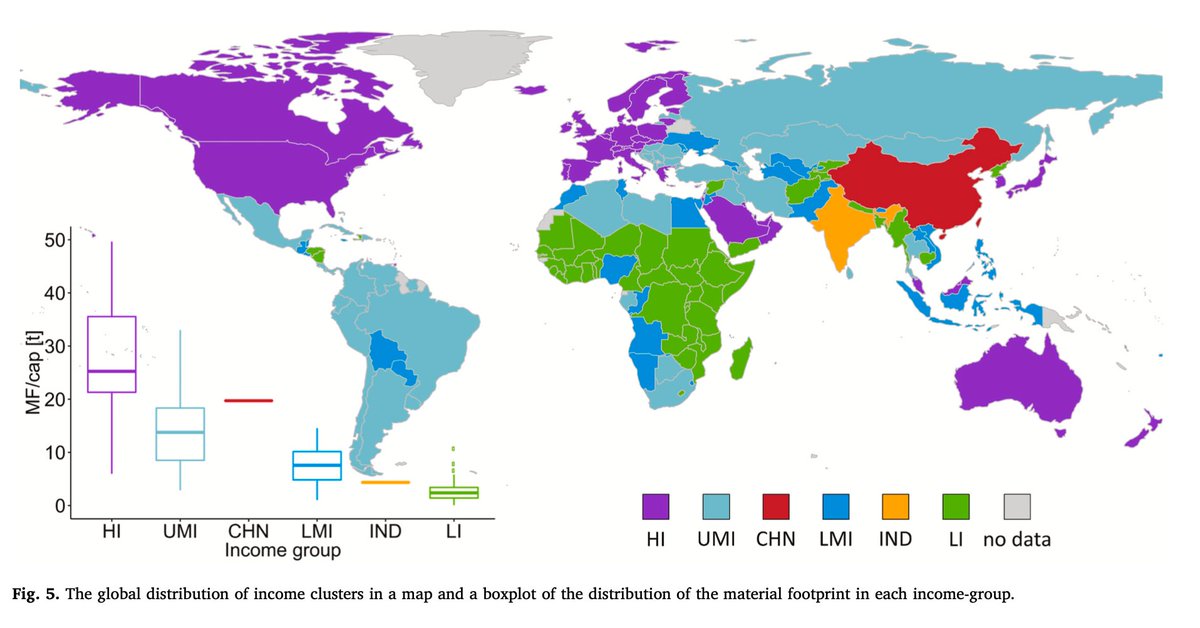

Here is a case of 'decoupling through burden shifting': high-income nations pride themselves in using less materials domestically, but this happens at the expense of using more materials in countries who export products to the global North.

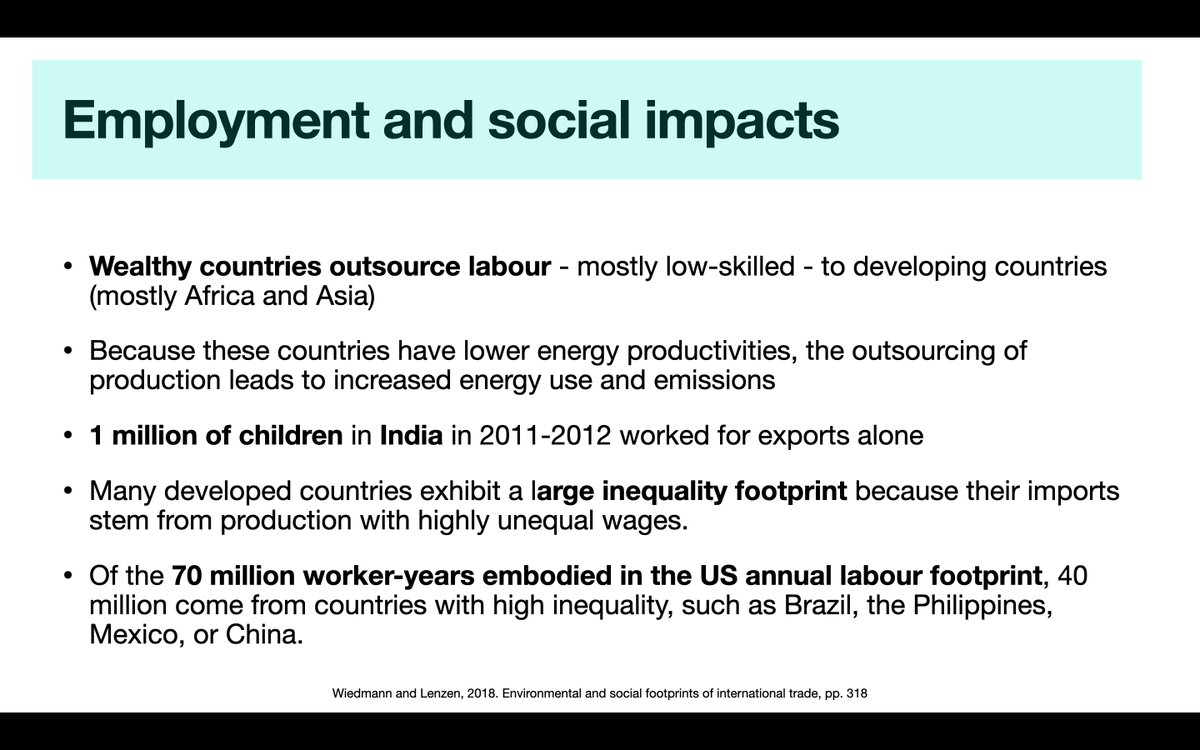

Similar patterns also exist for social impacts. For exemple, many rich nations have a high 'inequality footprint' because they import products from countries with very low wages.

One way of visualising these patterns is to look at the average physical distance of a national footprint, which becomes a measure of how much of the national social-environmental burden is shifted to other countries.

Take-home message: the green growth of rich nations is often a mirage caused by narrow indicators. When looking at the global picture, the illusion of decoupling disappears.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh