Bans now limit Western access to Putin's propaganda.

Most of us have no interest in propaganda. But there is reason to pause.

Not only are bans out of sync with the science of misinformation. They may also be detrimental to our fight for democracy.

An evidence-based 🧵 (1/16)

Most of us have no interest in propaganda. But there is reason to pause.

Not only are bans out of sync with the science of misinformation. They may also be detrimental to our fight for democracy.

An evidence-based 🧵 (1/16)

Since the 2016 US presidential election a myth has been created: People easily fall prey to misinformation.

Myth-busting is harder than myth-creation.

But the science is now clear, as this review shows: doi.org/10.1017/S13582…

Propaganda have little effects (2/16)

Myth-busting is harder than myth-creation.

But the science is now clear, as this review shows: doi.org/10.1017/S13582…

Propaganda have little effects (2/16)

A couple of examples may suffice.

A study did a meta-analysis of 40 studies on campaign effects on candidate preferences in the US and conclude that "the best estimate of the effects...is zero": doi.org/10.1017/S00030…

(3/16)

A study did a meta-analysis of 40 studies on campaign effects on candidate preferences in the US and conclude that "the best estimate of the effects...is zero": doi.org/10.1017/S00030…

(3/16)

Of course, US campaigns are not *real* propaganda.

So, let us look at Hitler.

There are quite a few studies on the effects of Nazi propaganda:

nber.org/system/files/w…

doi.org/10.1017/S00220…

doi.org/10.1093/qje/qj…

doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1…

doi.org/10.1017/S00030…

(4/16)

So, let us look at Hitler.

There are quite a few studies on the effects of Nazi propaganda:

nber.org/system/files/w…

doi.org/10.1017/S00220…

doi.org/10.1093/qje/qj…

doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1…

doi.org/10.1017/S00030…

(4/16)

The conclusion? Hitler's propaganda didn't have much effect on Nazi support. It likely increased support among the anti-semitic, but backfired among others.

What may have had effects were concrete problem-solving (roads) & indoctrination in schools, not radio propaganda.

(5/16)

What may have had effects were concrete problem-solving (roads) & indoctrination in schools, not radio propaganda.

(5/16)

Turning to Russian propaganda, we already know someting.

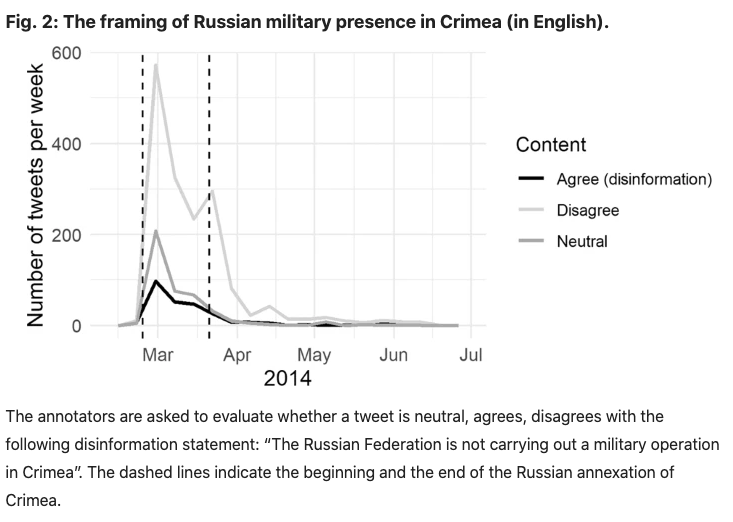

For example, most interactions with Russian disinfo during the Crimea invasion were countering it (nature.com/articles/s4159…) 👇 & Russian bots generally fail to reach new audiences: ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc…

(6/16)

For example, most interactions with Russian disinfo during the Crimea invasion were countering it (nature.com/articles/s4159…) 👇 & Russian bots generally fail to reach new audiences: ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc…

(6/16)

But why is propaganda not effective?

Because our psychology prioritizes prior beliefs. This makes us resistant to new information. We ignore inconvenient facts. But we also ignore misinformation.

Because Russian disinfo doesn't fit Western world views, it likely fails.

(7/16)

Because our psychology prioritizes prior beliefs. This makes us resistant to new information. We ignore inconvenient facts. But we also ignore misinformation.

Because Russian disinfo doesn't fit Western world views, it likely fails.

(7/16)

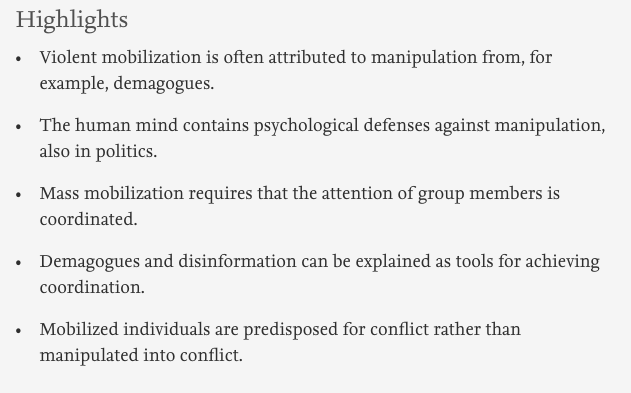

That doesn't mean that propaganda doesn't have effects on the already devoted ingroup. As argued in my own research, propaganda helps the already devoted coordinate their response against the enemy: doi.org/10.1016/j.cops… 👇

But that is an effect on *them*, not on *us*

(8/16)

But that is an effect on *them*, not on *us*

(8/16)

Let us say we agree that we aren't harmed by Russian propaganda. Does that mean that we shouldn't ban it?

It does.

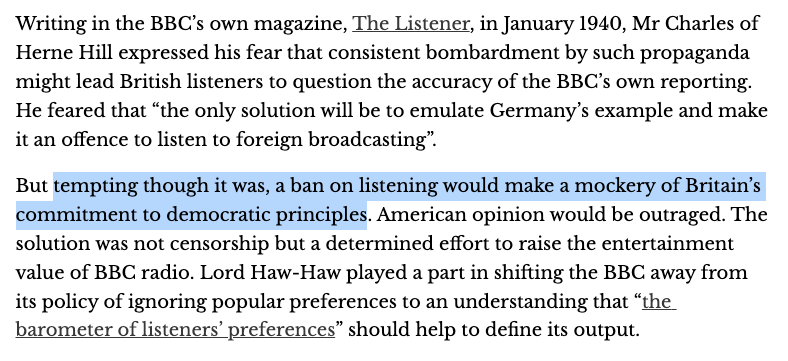

(A) It is antithetical to the values of an open society. This was recognized during WW2, where Nazi propaganda was *not* banned: theconversation.com/lord-haw-haw-p… 👇

(9/16)

It does.

(A) It is antithetical to the values of an open society. This was recognized during WW2, where Nazi propaganda was *not* banned: theconversation.com/lord-haw-haw-p… 👇

(9/16)

(B) Having opportunities to explore Russian propaganda may help citizens understand what we are finding *against*.

My bet is that the claim that Putin seeks to "denazify" a country run by a president with Jewish background is a motivating factor rather than the opposite (10/16)

My bet is that the claim that Putin seeks to "denazify" a country run by a president with Jewish background is a motivating factor rather than the opposite (10/16)

(C) If people want propaganda, they'll find it. For a tour of some of this, see this thread:

This also means that propaganda may reach you in all cases, even with a ban. (11/16)

https://twitter.com/Golovchenko_Yev/status/1498967275474456577?s=20&t=Jd7HktN-DGRxrV1w-W3w5w

This also means that propaganda may reach you in all cases, even with a ban. (11/16)

There are many alternative solutions, which do not involve bans. Again, ask those doing research on misinformation.

(A) Invest in media fact-checkers. It works (doi.org/10.1080/105846…), at least in the short run (nature.com/articles/s4156…). (12/16)

(A) Invest in media fact-checkers. It works (doi.org/10.1080/105846…), at least in the short run (nature.com/articles/s4156…). (12/16)

It can be difficult for fact-checkers to keep up with the de-bunking.

(B) Invest also in *pre-bunking*, i.e., empower people to be their own fact-checkers. People can learn to spot "fake news" with little instruction: doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1… (13/16)

(B) Invest also in *pre-bunking*, i.e., empower people to be their own fact-checkers. People can learn to spot "fake news" with little instruction: doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1… (13/16)

(C) Rather than turning the power to platforms, turn the power to individual users.

People should be allowed to avoid propaganda during war. Platforms should enable users to purge their feed of problematic propaganda sites with a click in "Settings".

(14/16)

People should be allowed to avoid propaganda during war. Platforms should enable users to purge their feed of problematic propaganda sites with a click in "Settings".

(14/16)

(D) The notion of an open society rests on the idea that the best antidote to conspiracy and falsehood is transparency. We have investigated this is the context of vaccine conspiracy: pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pn…. Transparency increases trust & decreases conspiracy beliefs. (15/16)

All in all, democratic principles & scientific evidence are aligned against banning information.

Disinformation is not so much a threat to democracy. It is the other way around: Democracy - the open flow of information - is the best weapon against disinformation. (16/16)

Disinformation is not so much a threat to democracy. It is the other way around: Democracy - the open flow of information - is the best weapon against disinformation. (16/16)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh