Are people who moralize facts, data & analytical thinking less likely to share false information?

No, in fact, they are *more* likely to do so.

New preprint with @A_Marie_sci: osf.io/k7u68/

A 🧵 on our counterintuitive finding, why it occurs & why it matters (1/10)

No, in fact, they are *more* likely to do so.

New preprint with @A_Marie_sci: osf.io/k7u68/

A 🧵 on our counterintuitive finding, why it occurs & why it matters (1/10)

Enter any conspiracy environment. All the focus is on facts, evidence & data. The rest of us are sheep. They are - in their own views - free-thinkers.

Here are a few studies:

doi.org/10.1177/174997…

link.springer.com/article/10.100…

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

(2/10)

Here are a few studies:

doi.org/10.1177/174997…

link.springer.com/article/10.100…

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

(2/10)

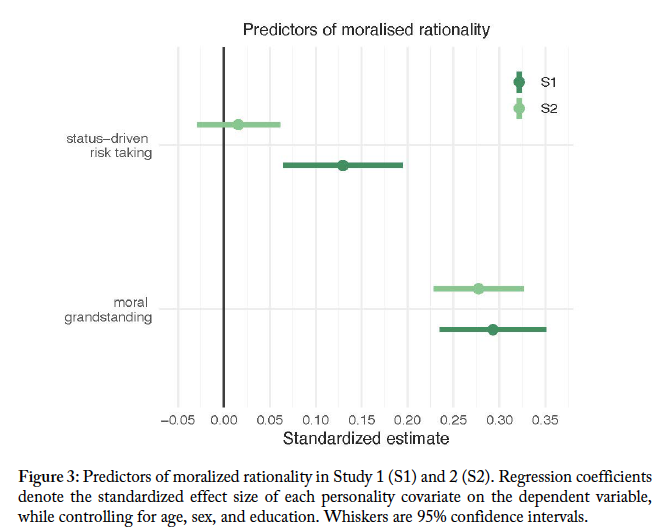

Essentially, conspiracy theorists are engaging in moral grandstanding when it comes to rationality. Moral grandstanding has been linked to status motivations (journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…), which again predict the sharing of false, hostile rumors (psyarxiv.com/6m4ts/). (3/10)

While moralization of rationality is often believed to be an antidote to misinformation (journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…), this entails that it may be significantly more complicated. (4/10)

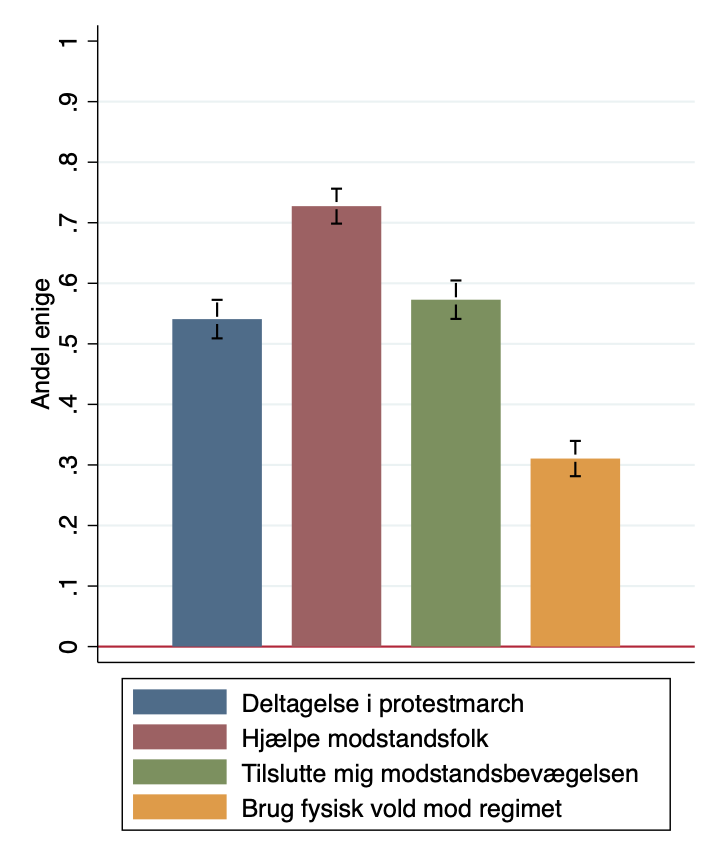

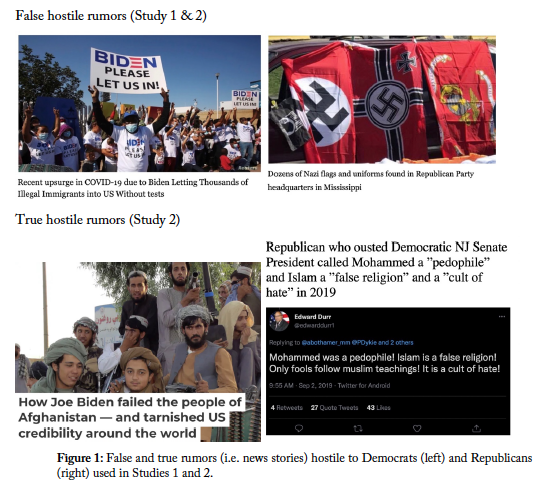

To examine this, we conducted two studies, 1 exploratory & 1 preregistered. Participants were exposed to hostile, denigrating & false news stories (as well as some true in Study 2) and provided self-reported sharing motivations (as well as accuracy judgements in Study 2). (5/10)

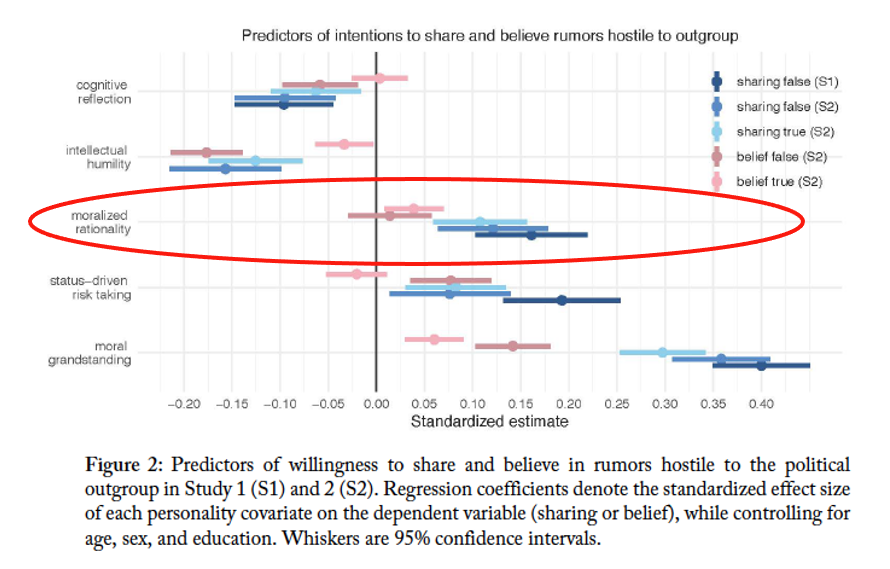

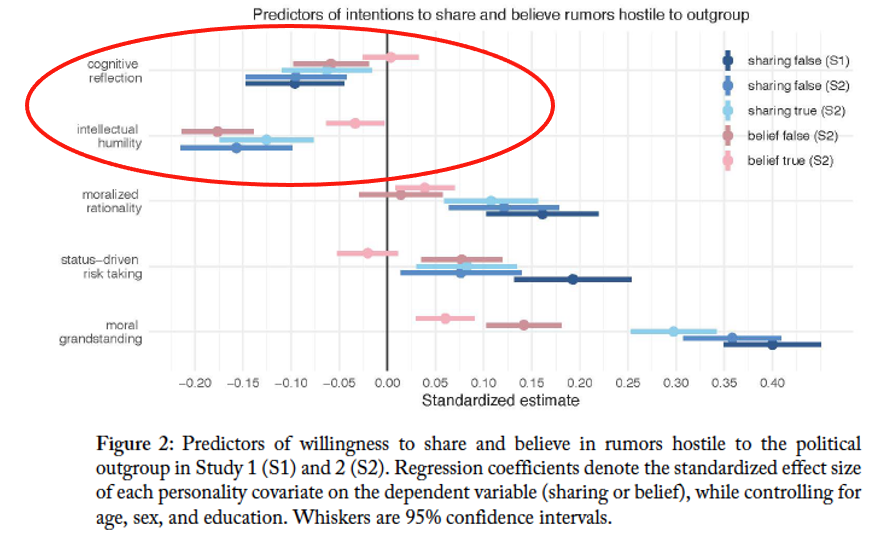

Moralized rationality (measured as here: journals.plos.org/plosone/articl…) *positively* predicts sharing of both true and false hostile news - as well as belief in true hostile news. (6/10)

Why? As predicted from the moralization literature, moralized rationality tracks status-traits related to grandstanding, which again predict sharing motivations. ~65 % of the association between moralized rationality & sharing is explained by status-oriented traits. (7/10)

Does that mean that data & evidence has no bearing on the circulation of false information? No. Shifting focus from moralized *motivations* to actual *abilities* to inhibit impulsive thinking, we find that such abilities lower sharing. (8/10)

To track this ability to inhibit impulsive thinking, we focus on the cognitive reflection task (nature.com/articles/s4146…) and intellectual humility (doi.org/10.1080/002238…). One feature of intellectual humility may be key: Knowing what you don't know & who knows better. (9/10)

All in all, we provide evidence that you shouldn't take expressed preferences for evidence, data & thinking at face-value. Those engaging most in such grandstanding may, in fact, be most susceptible to false information. Instead, we should value - and foster - humility. (10/10)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh