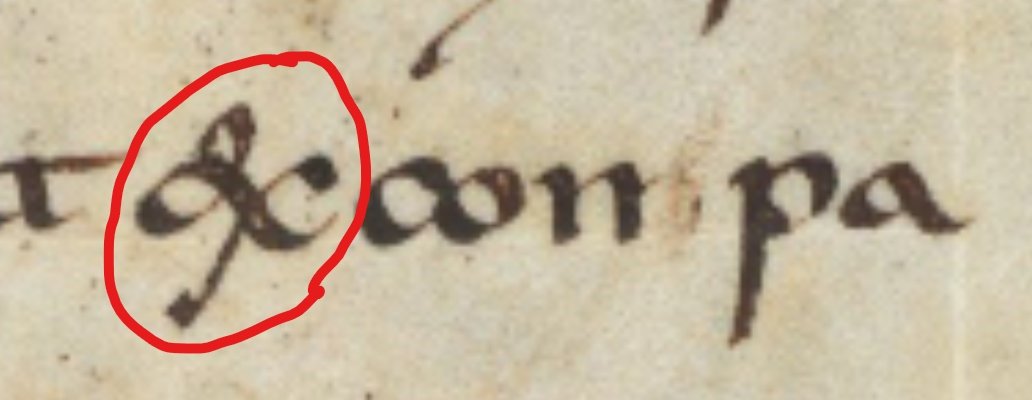

Today is the feast day of St. Thomas Aquinas, who is absolutely definitely and for real the patron saint of illegible handwriting. Here's his script in Vatican Library, Vat. Lat. 9850, written 1260-1265.

A note in this manuscript added by Aquinas' secretary Reginald of Piperno basically says that you could read this text too, if only you could find someone who could make sense out of Thomas' handwriting!

His handwriting is literally known as "littera inintelligibilis"!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh