How did Jesus pronounce his own name? Hint: it wasn’t Jesus. Or even Yeshua. Or anything at all like Yahashawa or the many variants diligently documented by @arabic_bad. 1/14

The pronunciations like Yahawashi etc. come from the idea that in the #Hebrew alphabet (especially the Paleo-Hebrew one), every letter represents a syllable. You can then read the original form of the name, יהושע (Paleo 𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤔𐤏) ‘Joshua’, as Ya-ha-wa-sha-i. Or something. 2/14

Other than pictures you see on the Internet, there is no basis for this way of reading Hebrew. It contradicts everything we know about how Hebrew was preserved, from how Hebrew names were spelled in Assyrian clay tablets to the reading traditions still used by Jews today. 3/14

So how do these reading traditions pronounce the name? Ignoring regional variation, there’s two versions. יהושע (mostly used for Joshua son of Nun) is read as yǝhōšūaʿ. The variant form ישוע (mostly used for Joshua the High Priest) is read as yēšūaʿ. 4/14

The second form developed from the first one. *yahōšūʿ, which is how I’d reconstruct the name in pre-Exilic pronunciation, contracted to *yōšūʿ. Then the rounded vowel *ō became an unrounded *ē before the following rounded *ū vowel, giving *yēšūʿ. 5/14

Basically, *yahōšūʿ is the Classical Biblical Hebrew form of the name and *yēšūʿ is the Late Biblical Hebrew form, used in the Second Temple Period. (Classical-ish) Zechariah uses *yahōšūʿ for Joshua the High Priest while (Late) Nehemiah uses *yēšūʿ for Joshua son of Nun. 6/14

You may have noticed that I’m not writing the a in the last syllable of *yahōšū(a)ʿ and *yēšū(a)ʿ. It wasn’t there historically and was added at a certain point to ease the pronunciation before the guttural ʿ sound (like so: ) at the end of the word. 7/14

We know from Greek transcriptions of Hebrew that this a (called patah furtivum/patach gnuva, ‘sneaky a’) wasn’t there yet in the early centuries CE. A word like mǝnaṣṣēaḥ ‘choir leader’, which also has it, was pronounced *mǝnaṣṣēḥ and transcribed in Greek as manassē. 8/14

In the same way, the #Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Septuagint) calls all the Joshuas iēsous. That’s *yēšūʿ (iēsou-) with -s added in the nominative case—that’s just a Greek thing. But no sneaky a: iēsous, not iēsouas. 9/14

The New Testament uses the same form as the Septuagint. By way of #Latin iēsūs (borrowed straight from iēsous), this gives us English Jesus. 10/14

In Rabbinic texts, Jesus of Nazareth is called יֵשׁוּ yēšū. This looks like *yēšūʿ with the guttural ʿ left off, something that Galileans were known to do. (The explanation from the phrase ימח שמו וזכרו ‘may his name and memory be erased’, is a backronym.) No sneaky a. 11/14

#Syriac, a major language of Middle-Eastern Christianity, has two versions. West Syriac ܝܶܫܘܽܥ yešuʿ looks like it’s straight from *yēšūʿ. East Syriac ܝܼܫܘܿܥ išoʿ looks like it goes back to *yešuʿ with short vowels… 12/14

… which is cool, because shortening long vowels seems to be another thing that was typical of Galilean Aramaic. So *yešuʿ may have been how Jesus of Nazareth & friends pronounced *yēšūʿ themselves. Again: no sneaky a in Syriac. 13/14

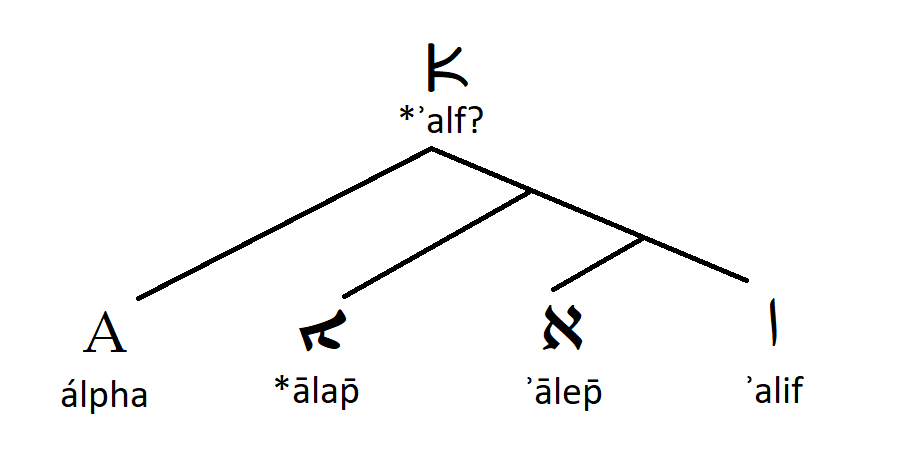

In #Arabic, Christians say yasūʿ, which could be from Syriac if it wasn’t borrowed directly from Hebrew. How the Qur’an turned the name into عِيسَى ʿīsā̈ is a longstanding problem (personally I suspect influence from مُوسَى mūsā̈ ‘Moses’). And I’ll leave you with a diagram. 14/14

d'oh, how Hebrew was *pronounced

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh