Oh, Rome, the eternal city, the magnificent place, the capital of the mighty #RomanEmpire. Right?

Wrong. Ok, right, but only partially.

The capital (s) of the Roman Empire (as there was more than one) and the shift to the East.

A thread 🧵

Wrong. Ok, right, but only partially.

The capital (s) of the Roman Empire (as there was more than one) and the shift to the East.

A thread 🧵

A town founded in 753 BC at the banks of Tiber, by the first century BC, Rome turned into the most important city in the Mediterranean. Its optimal location, in the middle of #Italy, right in the centre of the Mediterranean basin, resulted in the rapid growth of the city. /1

It also helped that #Rome was the capital of the rising power, the Roman Republic, which by the end of the first century BC, defeated all its major rivals, including Carthage and the Hellenistic Kingdoms in the East. /2

Rome's influence and power further increased after the emperor #Augustus commissioned an ambitious building program that reshaped the cityscape. Augustus did not make a "city of brick into a city of marble," but he added a lot of that marble. /3

More importantly, under Augustus, Rome became the capital of the probably most powerful Empire in the ancient world. Also, the conquest of #Egypt allowed Augustus and his successors to provide the citizens of Rome with free grain, further increasing the city's population. /4

By the second century, Rome had one million people, becoming the largest city in the ancient world. Or at least in Europe.

However, its time of glory was nearing its end. And that was, ironically, the result of the immense power and size of the Roman Empire. /5

However, its time of glory was nearing its end. And that was, ironically, the result of the immense power and size of the Roman Empire. /5

Simply put, by the second century AD, Roman Empire became too big to be controlled from Rome. Hadrian was first to realize this, halting the expansion and fortifying the borders.

However, it would be a so-called crisis of the third century that would bring a major change.../6

However, it would be a so-called crisis of the third century that would bring a major change.../6

The increased pressure at the borders required an immediate emperor's presence in the area. Don't forget where the emperor was, there was the court, there was the army, and there was money, power, and influence. /7

And if the emperor was absent for too long, the local aristocrats and army would choose their own. No wonder the usurpation became endemic during the third century. As did the civil wars.

Thus, the center of the Empire moved from Rome to the towns closer to the border. /8

Thus, the center of the Empire moved from Rome to the towns closer to the border. /8

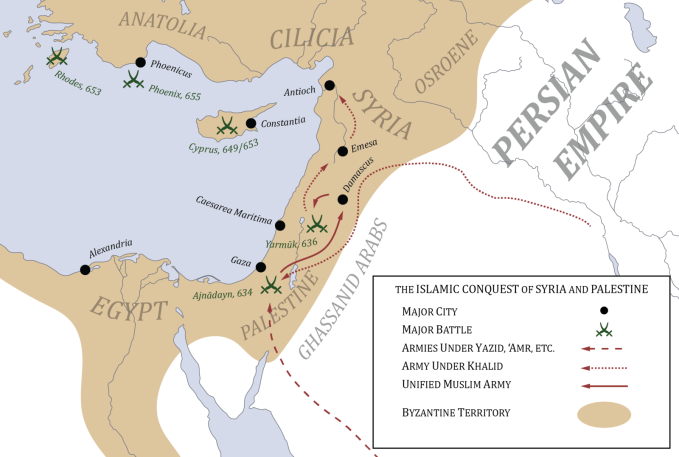

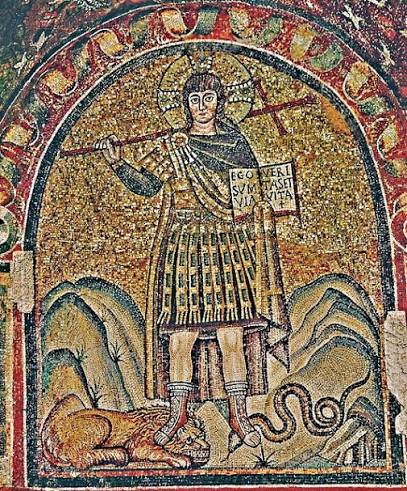

And once the center shifted from Rome, it began losing its political importance, retaining the symbolic one. The new (temporary) capitals were better suited to control the vast Empire. Trier on the Rhine (pictured), Antioch near the Persian border, or Milan in northern Italy. /9

At the very end of the third century, during Diocletian's Tetrarchy, four emperors ruled the Empire from four capitals. Not a single one of them was Rome. In fact, for most of the century, no emperor even visited the old capital. /10

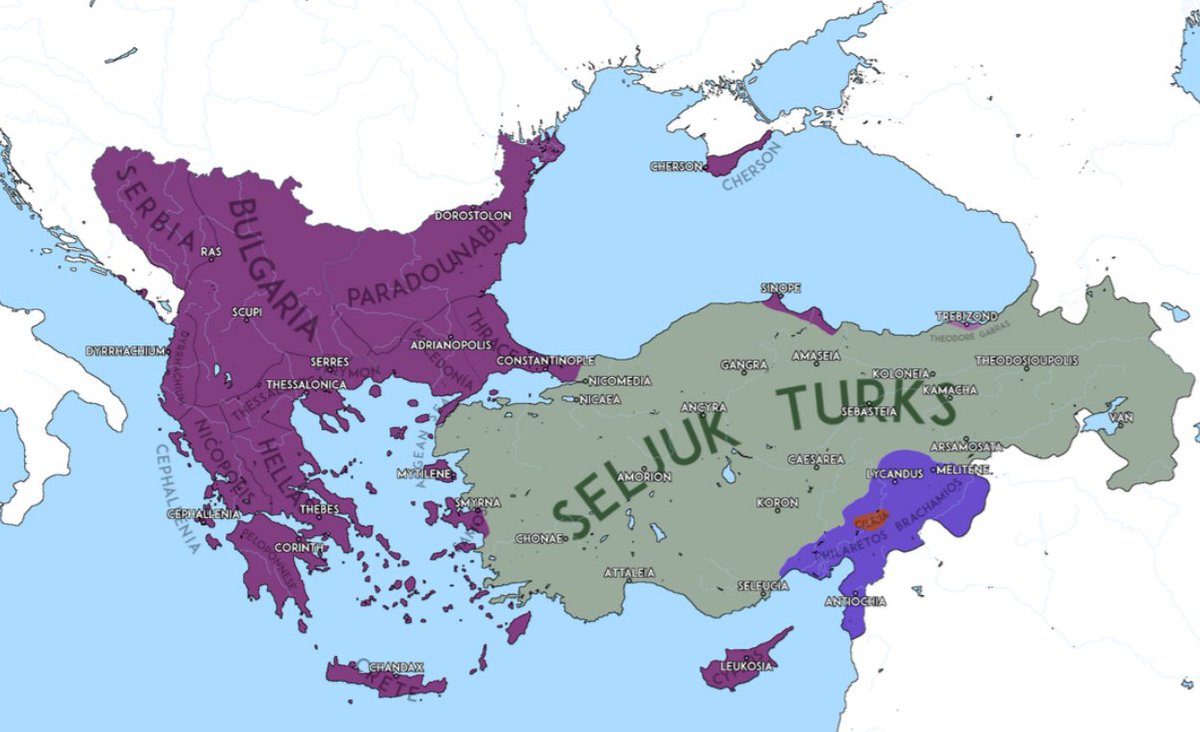

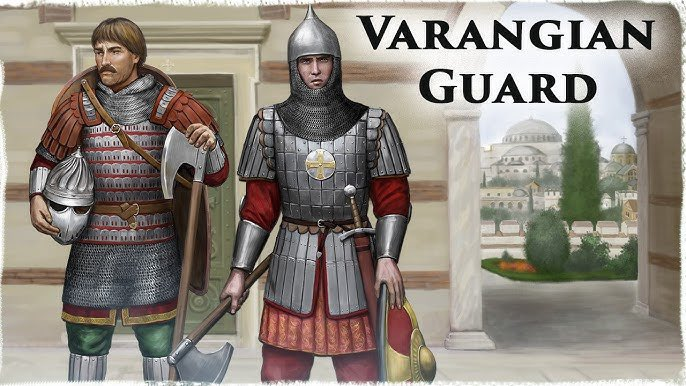

And after Tetrarchy collapsed, #Constantine the Great sealed the deal, moving the capital to Constantinople. A great choice, as Constantinople was close to both Persian and Danubian frontier, and more importantly, it was easily defensible. /11

However, even Constantine was aware that the Empire was too big to be ruled by one man only. The Empire required at least two emperors, or even three augusti, to be ruled effectively.

And each of them had its own capital, and Rome was not one of them. /12

And each of them had its own capital, and Rome was not one of them. /12

When the Roman West began falling apart in the fifth century, the capital moved to Ravenna, a city in northern Italy, which, again, was well protected by the surrounding marshes and fortified by the strong bulwark. Truly a seat for the Roman emperor. /13

Thus, when Rome was sacked first time by Alaric, and then by the #Vandals, the Empire continued to function as usual. Truly, it was a shock to see the eternal city plundered. But again, it was not a political, but a symbolic loss. Ravenna was safe. /14

More importantly, Constantinople was hardly affected. By that time, however, Roman West was at its last gasp. Thus when the last Roman emperor in the West was deposed, no one cared.

The true center of the Empire was in the East, and it will remain so for thousand more years /15

The true center of the Empire was in the East, and it will remain so for thousand more years /15

In fact, already in the last years of the Republic, Mark Antony wanted to move the capital eastwards to Alexandria. And it was not a bad idea, as the East was always better urbanized, wealthier and more developed than the West (except perhaps Italy). /16

And Antony was not the only one. Caligula, too wanted to move the capital to Alexandria. Some would say that this was another case for his madness, but taking into consideration Roman obsession with Parthian Empire and later Sassanids, Caligula's plans had some merit. /17

However, both in the case of Antony and Caligula, the Roman traditional elite - the Senate - had considerable power. That allowed Octavian (future emperor Augustus) to declare war on Antony, or in Caligula's case, result in his violent death. /18

But in the end, as we could see, the Eastern option prevailed.

Rome, however, retained its importance as the seat of the Pope, which remains to be up to the present day. But as the imperial center, its role ended as soon as the Empire reached its apex. /19

Rome, however, retained its importance as the seat of the Pope, which remains to be up to the present day. But as the imperial center, its role ended as soon as the Empire reached its apex. /19

It is hard to say what would happen to Rome if Antony managed to win the Parthian campaign. #History would certainly be different. But this topic, the lure of the East, the Roman obsession with Parthia and the Sassanids is for another time. /20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh