Some thoughts on the Proto-#Semitic word for 'woman, wife' on this #InternationalWomensDay.

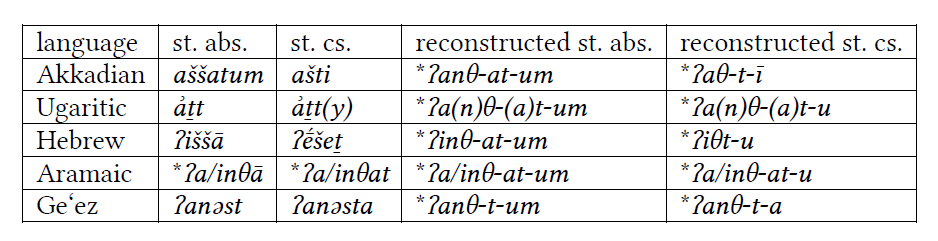

The broad outlines of the reconstruction are clear, since many different languages have pretty similar forms. The stem must be something like *ʔV(n)θ-(a)t-. 1/11

The broad outlines of the reconstruction are clear, since many different languages have pretty similar forms. The stem must be something like *ʔV(n)θ-(a)t-. 1/11

This *-(a)t- is the feminine suffix. From the same consonantal root, we also find some other words: #Arabic ʔunθā 'feminine', #Amorite(!) /taʔnīθ-um/, predictably bizarre Modern South Arabian forms like #Jibbali teθ, etc. (for Ancient South Arabian, see below). 2/11

Reconstructing the main word runs into three problems. From right to left:

1) *-at- or *-t- in the suffix?

2) *n or no *n?

3) *a or *i in the first syllable? 3/11

1) *-at- or *-t- in the suffix?

2) *n or no *n?

3) *a or *i in the first syllable? 3/11

Different languages do different things with the two forms of the feminine suffix, *-at- and *-t-. #Akkadian and #Hebrew both show *-at- in the absolute state (Akk: status rectus) and *-t- in the construct. That interchange happens in other words too, so: let's choose that. 4/11

The other languages have then generalized their preferred form of the suffix: *-at- in #Aramaic and *-t- in #Geez. So far, so good. 5/11

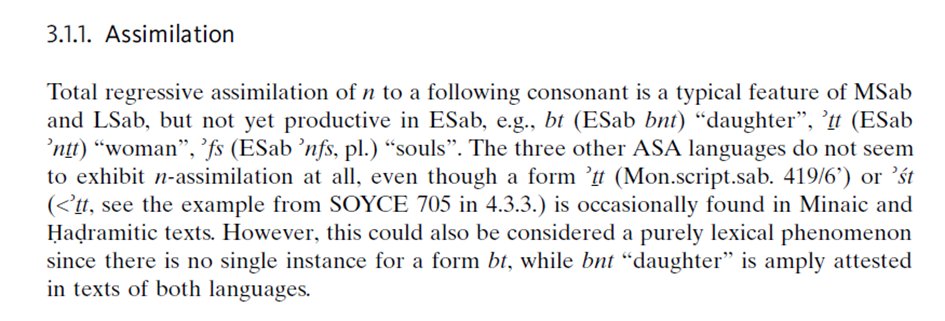

Next: wherever it's visible, the absolute state shows *n (assimilated in some languages). But #Akkadian and #Hebrew seem to be missing the *n in the construct state, 'woman/wife of'. What gives? 6/11

It's awfully coincidental that the *n is only missing in languages where it assimilates to following consonants. Based on our reconstruction of *-t- for the suffix in the construct, maybe the apparent loss of *n results from geminate simplification: 7/11

Something like *ʔanθ-t- (cf. the Ge'ez reflex) > *ʔaθθ-t- > *ʔaθ-t- (giving the Akkadian construct stem). Similar processes eliminate unwieldy geminates in other construct states: Akkadian šar 'king of' < *šarr, kak 'weapon of' < *kakk; Hebrew šḗšeṯ '6 (m.)' < *šišš-t. 8/11

I like this explanation because it relies on two processes we already know instead of inventing something new, maybe involving syllabic nasals. Data from #Minaic and #Hadramitic suggests something more complex is going on but I don't know what to make of it. 9/11

Finally: *a in the first syllable like most languages or *i like Hebrew and some forms of Aramaic? It would be nice to connect this to the not-quite-explained behaviour of the nasal, but I don't see how, so I'm going to invoke contamination with *ʔīs- (< *ʔins-) 'man'. 10/11

So that leaves us with a Proto-Semitic paradigm of absolute *ʔanθ-at-, construct *ʔanθ-t-, with the usual triptotic case endings. Normally, we don't reconstruct consonant clusters like the one in the construct, so that's interesting. But I think I like it. 11/11

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh