#THREAD

Concerns are growing over TV impartiality on @BBC, #TalkTV, & GB "News".

A timely new study: 'Does the Political Context Shape How “Due Impartiality” is Interpreted? An Analysis of BBC Reporting of the 2019 UK & 2020 US Election Campaigns'.

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

Concerns are growing over TV impartiality on @BBC, #TalkTV, & GB "News".

A timely new study: 'Does the Political Context Shape How “Due Impartiality” is Interpreted? An Analysis of BBC Reporting of the 2019 UK & 2020 US Election Campaigns'.

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

Balance and impartiality are central principles in journalism, but this study argues their conceptual application in news reporting should be subject to more academic scrutiny.

In the UK, the way “due impartiality” has been applied and regulated by broadcasters has raised concerns about promoting a ‘she-said-he-said’ style of reporting, which constructs balance but not scrutiny of competing claims.

This study analysed how the UK’s “due impartiality” was applied by journalists in different political contexts by assessing how the @BBC dealt with competing party-political claims.

Researchers developed a nuanced quantitative analysis of @BBC journalist interactions (N = 967) with claims made by the four main party leaders during the 2019 UK and 2020 US elections.

Overall, the research found @BBC reporting robustly challenged claims by US politicians, whereas coverage of UK politicians often only conveyed claims & counterclaims with limited journalistic intervention, particularly on television @BBCNews.

The researchers argue that impartiality should be viewed more as a fluid than fixed concept given that the context shapes how it is applied.

As concerns about misinformation have grown over recent years, they conclude that more finely tuned studies are needed to understand how journalists apply concepts about balance and impartiality in political reporting.

Over time the ethos of impartiality and balance shaped @BBC output, whether, as argued by critics, in appearance only, or in genuine principle.

But whatever the rationale, the trope of covering "both sides" of an issue shaped much of twentieth-century journalism practice.

But whatever the rationale, the trope of covering "both sides" of an issue shaped much of twentieth-century journalism practice.

The continued dominance of this model was recognised by the 2007 Bridcut Review of @BBC output which suggested that the “seesaw” metaphor of reporting “both sides” (balance) might be replaced by a wagon wheel metaphor allowing more & greater nuance of opinion (impartiality).

The ethos of multiple “balanced” perspectives as a means of informing the public in an impartial manner has of course been extensively critiqued.

Work from the Glasgow University Media Group notably and consistently showed how the range of viewpoints aired was limited to a narrow and elite choice of sources rather than a full range of perspectives.

The @BBC acknowledged that concerns over balance were detrimental to its reporting of the #ClimateCrisis. A strict adherence to balance on climate change led to instances where the scientific consensus on Climate Change was incorrectly balanced with climate denialism.

To put this more succinctly, truth was balanced with untruth.

In this instance, balance allowed for consideration of the impartiality requirement by taking account of a full range of views, but not that the relative weight of opinion had changed over time.

In this instance, balance allowed for consideration of the impartiality requirement by taking account of a full range of views, but not that the relative weight of opinion had changed over time.

Despite criticism of both-sideism & its limitations in affording democratic norms, it is generally seen as a model which aims for impartiality. However, the "he-said-she-said" reporting style is premised on an understanding that both sides offer factually accurate positions.

In the current political landscape, increasingly characterised by #misinformation, the credibility of what politicians say has come under greater scrutiny. This study examines two actors—Trump &Johnson—that have well-documented records of making false or misleading statements.

The Washington Post Fact-Checker detailed over 30,000 statements from Trump during his presidency which they labelled as false.

Meanwhile, Oborne is one of many who have extensively detailed episodes of Johnson making deceitful statements.

books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr…

Meanwhile, Oborne is one of many who have extensively detailed episodes of Johnson making deceitful statements.

books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr…

A recent tool seen as an important buttress against misinformation, & increasingly employed by media organisations, are specific fact-checking Depts (eg Channel 4’s FactCheck or the Washington Post’s Fact Checker) or stand-alone organisations (such as PolitiFact or Full Fact).

While fact-checking is, of course, part and parcel of all news reporting, dedicated fact-checking services aim to examine in detail claims made by actors such as politicians and reach conclusions about the veracity of the claim.

Typical fact-checking articles use independent expert opinion, reliable sources of data & numerous triangulating sources to enable them to reach a conclusion.

In the UK, @BBCRealityCheck was established in 2017, and, according to the Head of @BBCNews at the time, the service would be “weighing in on the battle over lies, distortions and exaggerations”.

theguardian.com/media/2017/jan…

theguardian.com/media/2017/jan…

Birks examined the extent to which fact-checkers, including @BBCRealityCheck, weighed in during the 2017 & 2019 UK General Elections.

theconversation.com/uk-election-20…

theconversation.com/uk-election-20…

This work found a greater embedding of fact-checking journalism within main news coverage, yet also detailed the public’s concerns about what they perceived as a subjective form of reporting being inherently biased.

Nonetheless, recent studies suggest the public are receptive to greater fact-checking in routine journalism.

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.117…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.117…

Fact-checking as a form of explanatory journalism conforms well to the wagon wheel metaphor outlined in the Bridcut Review and is therefore an influencing style one might expect to now see in @BBCNews output beyond @BBCRealityCheck.

Yet, as noted by Graves, fact-checking takes time, and often does not finish at a deadline, leading to one interviewee remarking to Graves that, “[journalists] don’t have time or they’re on deadline and … so it becomes ‘he said, she said’.”

degruyter.com/document/doi/1…

degruyter.com/document/doi/1…

This new study examines the degree to which claims, and counterclaims are reported by @BBCRealityCheck, & consider how they interpreted “due impartiality.”

The hypothesis is that, despite @BBC guidelines, the operationalisation of impartiality may change dependent on the electoral context (domestic vs foreign), the specific politician being reported on, & the media platform (online, in a fact-checking article, or TV news bulletin).

Methodologically, a politician's claim was operationalised as any instance where one of the four politicians (Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Jeremy Corbyn, & Boris Johnson) made any politically relevant statement where the statement’s veracity could be challenged.

Manifesto pledges of future intentions were not included. Politically relevant statements encompassed all policy areas broadly conceived, electoral processes and personal statements with potential electoral influence.

Interactions were defined as instances where an element within the story explicitly or partially/implicitly challenged a politician’s claim (Corrective Interactions—CIs) or completely or partially validated the claim (Validating Interactions—VIs).

Null Interactions (NIs) were also recorded (instances where a claim was published but received neither a corrective nor validating interaction).

The research found journalists applied different levels of scrutiny when covering political leaders during the US & UK elections.

The research found journalists applied different levels of scrutiny when covering political leaders during the US & UK elections.

Researchers discovered the level of journalistic interactions varied when reporting different political leaders.

For Trump, 73% (Johnson 70%) of journalistic interactions with his claims were 'Corrective Interactions' (CIs) Corbyn (50%) & Biden (38%) had lower proportions CIs.

For Trump, 73% (Johnson 70%) of journalistic interactions with his claims were 'Corrective Interactions' (CIs) Corbyn (50%) & Biden (38%) had lower proportions CIs.

Of the CIs, 71% of Trump’s were explicit compared to 65% for Corbyn, 53% for Johnson and 50% for Biden.

An example of a typical Explicit Corrective Interaction appeared on Oct 27th when a @BBC Reality Check article covered a claim made by Trump about Covid-19 that “[the US has] one of the lowest mortality rates.”

It was immediately followed by the journalist stating: “Verdict: That’s not right. The US ranks high globally in terms of covid deaths per person.”

This form of abrupt correcting by a journalist was reserved almost exclusively for Trump.

This form of abrupt correcting by a journalist was reserved almost exclusively for Trump.

When UK politicians were explicitly corrected, even on @BBC Reality Check, such an abrupt form was not utilised, & strong rebuttals were usually delivered by quoting other political operatives—invariably a Labour politician countering a Conservative claim or vice-versa.

Overall, Trump made 187 unique claims, which received 315 CIs - for every claim he made, he was corrected on average 1.7 times. Several of Trump’s statements, eg to have 'built the greatest economy in the history of the US', received detailed rebuttals with numerous CIs.

For Boris Johnson, his 168 unique claims received 213 CIs, meaning the average corrective was 1.3 for every claim.

Although extensive correcting of Trump did occur, there were still instances where unsubstantiated claims were not challenged.

Although extensive correcting of Trump did occur, there were still instances where unsubstantiated claims were not challenged.

Following his stay in hospital with Covid-19, for instance, Trump’s return to the campaign trail was covered by @BBCNews at Ten on 13th October. The anchor introduced the item with “The president told his supporters that he was now ‘immune’, and that he felt ‘powerful’.”

The claim of immunity went unchallenged. Yet, official World Health Organisation guidance and the National Health Service position at that time was that it was unknown whether having Covid-19 granted natural immunity to further incidence of catching the virus.

In the same @BBCNews item, Trump also made false statements against Joe Biden, saying, “We have somebody running that’s not 100%. He’s not 80%. He’s not 60%.”

This unsubstantiated claim that Biden was mentally unfit to hold the office of president was also reported on @BBCNews online on 14th October, with Trump saying, “He's shot, folks. I hate to tell you, he's shot… can you imagine if I lose to a guy like this? It's unbelievable.”

Again, this falsehood went unchallenged. How far journalists should challenge or even ignore false claims has been subject to fierce debate over recent years.

While it could be argued that repeating falsehoods may help promote and spread misinformation, research has suggested that reporting falsehoods in the context of a corrective can correct misunderstanding.

cambridge.org/core/elements/…

cambridge.org/core/elements/…

However, reporting it is still an editorial choice, a choice which, without rebuttal, likely adds a layer of legitimacy to the claim - see 'Think Tanks, Television News & Impartiality: The ideological balance of sources in @BBC programming' (2019).

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.108…

The researchers found a high level of journalistic interacting with, and scrutiny of, political claims made by all four leaders.

However, as illustrated in Table 2, there were clear differences in the way that @BBC journalists applied them in US & UK election campaign coverage.

However, as illustrated in Table 2, there were clear differences in the way that @BBC journalists applied them in US & UK election campaign coverage.

On stories related to the US election, @BBC journalists were the source of just over half of CIs with claims by Trump (51%) & Biden (52%) but far fewer for Corbyn (21%) & Johnson (27%) in UK election coverage.

Rather than issuing personal correctives, in UK election coverage journalists typically edited coverage so other politicians or parties corrected the claims for them—a classic "she-said-he-said" style of reporting.

On closer inspection, researchers found it was far more common for journalists to draw on direct quotes as correctives in UK election coverage than in US election coverage.

Conversely, US coverage contained much higher correctives with journalist’s own intervention into a claim being the main type of interaction.

They also found correctives of Trump & Biden were more likely to appear immediately following a claim than those for Johnson & Corbyn.

They also found correctives of Trump & Biden were more likely to appear immediately following a claim than those for Johnson & Corbyn.

Overall, the data suggests that @BBC journalists were far more reluctant to directly correct UK politicians than US politicians despite, in theory, applying the same “due impartiality” to news output.

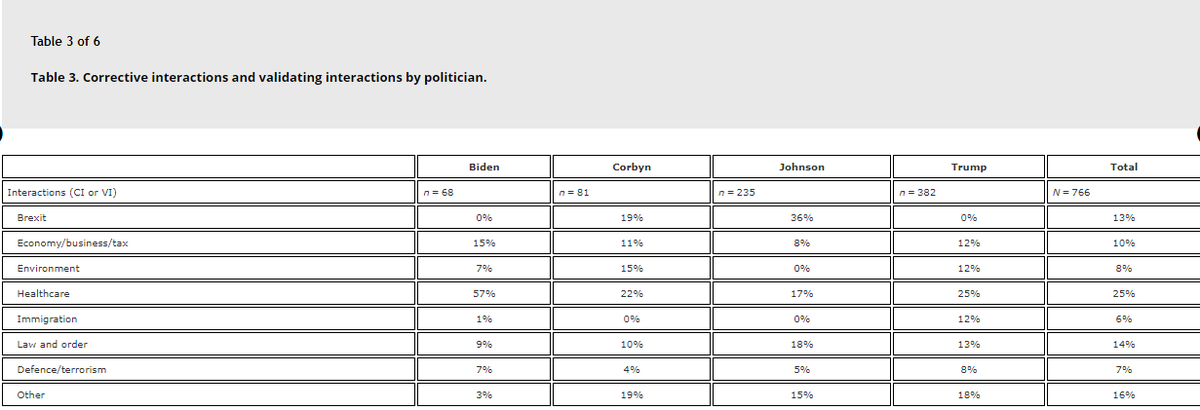

Table 3 shows policy topics on claims interacted with by journalists. For the UK, they broadly fall in line with the issues both leaders were championing. For Johnson, it was his claims on Brexit (almost all being correctives) & crime & law & order issues.

By contrast, most interactions with claims made by Corbyn were on healthcare, Brexit (illustrative of this issue’s dominance in the campaign), & the environment.

In the US election, Covid-19 understandably dominated the coverage, but more so in the reporting of Biden, with coverage of Trump more balanced across topics. However, it was notable that Trump’s statements about immigration were frequently covered and corrected.

Table 4 illustrates the different ways journalists interacted with claims according to the @BBC platform: either the @BBCNews at Ten broadcast, BBC online or the BBC Reality Check pages of the website.

All 134 Reality Check interactions were either correctives (76%) or validations (24%).

Of course, since Reality Check aims to provide a fact-checking service, this degree of scrutiny of claims and holding politicians to account is perhaps to be expected.

Of course, since Reality Check aims to provide a fact-checking service, this degree of scrutiny of claims and holding politicians to account is perhaps to be expected.

But it does confirm the @BBC’s fact-checking services deliver a more robust approach to challenging claims than TV & online reporting.

Many online stories provided a link to a Reality Check fact-check, allowing readers to check the veracity of claims.

Many online stories provided a link to a Reality Check fact-check, allowing readers to check the veracity of claims.

However, on television news, @BBC Reality Check was not mentioned even once. It is worth pointing out of course that viewers for the BBC News at Ten on television are vastly greater than the number who would be exposed to a Reality Check article.

While Reality Check corrected or validated all claims, the non-null interactions (no guidance about the veracity of a claim) with claims online (80%) were notably greater than in broadcast (59%).

The 40% null interaction figure for broadcast meant that many statements made by the politicians were broadcast without any guidance to viewers about the veracity of a claim, or even exposure to a counterclaim by an opposition politician.

Researchers did note instances where a claim was met with a counterclaim which though related and on topic did not directly address the original claim—a "he-said-she-said-something-related" style.

BBC Reality Check applied “due impartiality” differently with a far more robust approach to challenging claims & counterclaims. Most Reality Check correctives were in the form of journalist’s own interpretation. frequently these were clear-cut verdicts such as “that’s not right”.

This compared to the far greater use of sources providing quotes as correctives in other online stories & on broadcast eg an item on the leader’s debate included the claim the @Conservatives were building 40 new hospitals, balanced by Corbyn saying the true figure was six.

To help illustrate the differences between reporting across BBC platforms, it is worth reflecting on how this specific claim about building forty new hospitals was comparatively dealt with by @BBC television news, online news, & Reality Check.

Prior to, & during the election period, Conservative politicians repeatedly claimed that the Conservative government was building 40 new hospitals. This claim was covered in the 6th December @BBNews at Ten item.

Here, apparently responding to previous criticism of the claim, Johnson explained in more detail and ended with a diluted claim of, “there will be forty new hospitals.” Corbyn then argued that the claim of building 40 hospitals became twenty and later six.

It was presented as a “he-said-he-said” story. It is pertinent that government documents, available at the time, showed that over half of the planned builds were to existing facilities, & therefore not “new” hospitals by any reasonable interpretation of the term.

The original claim of 40 hospitals was extensively rebutted on Reality Check & was clearly labelled as misleading & inaccurate. Amongst other correctives, many #NHS Trust sources were quoted as stating that there were no plans for, let alone active construction of, new hospitals.

The detailed contradiction concludes with, “so it's not correct to suggest that 40 new hospitals are currently being built.”

It is a well-formed fact-checking article which may be summarised as “he-said-he’s-wrong.”

It is a well-formed fact-checking article which may be summarised as “he-said-he’s-wrong.”

BBC online featured a story on December 3rd with the following claim: “Boris Johnson is constantly championing the 40 new hospitals he wants to see built” hyperlinked to a Reality Check page which summarises the full Reality Check article, including the same blunt conclusion.

The journalist here uses the hyperlink facility as a form of corrective rather than including a judgment within text, thus effectively outsourcing the corrective to a @BBC colleague.

In contrast, @BBC television news coverage, simply balanced competing claims by first featuring the claim by Johnson about 40 new hospitals & then offering a rebuttal from Corbyn - highlighting the dangers of 'false equivalence'.

The potential dangers of giving false equivalence to competing claims when the weight of evidence significantly supports only one claim has been widely discussed.

The weight of evidence here, provided by one part of @BBCNews, was that 40 new hospitals were not being built, but perhaps due to concerns of appearing impartial in the more high-profile flagship TV News bulletin meant that this conclusive judgement was not conveyed to audiences.

The conclusive judgement about the forty new hospitals claim was limited to those either directly reading @BBC Reality Check or those motivated enough to click through to the online story to find the fact-check.

The researchers focus on this claim to illustrate how @BBC television news simply balanced soundbites on an issue, whereas BBC online news provided a far more robust & nuanced examination of this policy commitment because of the fact-checking role played by BBC Reality Check.

In the UK government's Health Infrastructure Plan, then Health Secretary Matt Hancock wrote, “We’re giving the green light to more than 40 new hospital projects across the country, six getting the go-ahead immediately, & over 30 that could be built over the next decade.”

A claim of “40 new hospital projects… that could be built” is different to “will be 40 new hospitals,” & very different to “we are building 40 new hospitals.” But only the @BBC Reality Check's service provided a necessary degree of scrutiny to challenge a key manifesto promise.

It is perhaps to be expected that online news has a greater level of journalistic interaction with claims than broadcast news given limited TV airtime. To investigate this assumption, they worked out the comparable length of time it took to read broadcast & online coverage.

They found the average duration of broadcast items was 130 seconds, with online items on average taking around 2.5 times that duration to read. On average, 1.3 claims were made per online item and 0.9 per broadcast item.

This meant that, standardising for duration, approximately double the rate of claims were made in broadcast news than online. Yet, each inaccurate claim in broadcast was corrected half as frequently as online.

This meant that after controlling for the different formats of television & online platforms, politicians were allowed to make far more claims on television that were far less likely to be contested.

In other words, & importantly, the medium is the message: online @BBC reporting applied “due impartiality” far more robustly than television coverage.

Different story archetypes perhaps provide a neat, if imperfect, summation of these findings.

Different story archetypes perhaps provide a neat, if imperfect, summation of these findings.

On broadcast, the stories are typically “he-said-she-said.” Online they are more akin to, “he-said-she-says-he’s-wrong,” whereas Reality Check has a model closer to “he-said-he’s-wrong.”

This study developed a new systematic research design and conceptual understanding of how impartiality was interpreted and applied across different political contexts and media platforms.

The UK case study examined @BBCNews output which is required to be duly impartial when reporting all election campaigns, whether domestic or foreign.

Yet the findings illustrated clear differences in how impartiality was applied in the UK & the US context.

Yet the findings illustrated clear differences in how impartiality was applied in the UK & the US context.

When covering UK elections, @BBC journalists tended to resort to a more 'she-said-he-said' style of reporting compared to the reporting of the US election where political claims were more directly challenged.

Nossek’s work has suggested there are differences in how journalists report foreign and national issues—and the case study about election reporting in the UK and US has reinforced this perspective.

However, the research has added more empirical weight & detail to precisely how journalists' apply impartiality when reporting a "foreign" (US) & "national" (UK) election campaign.

Put simply, @BBC journalists were more emboldened when reporting a foreign than domestic election, directly questioning statements by Donald Trump.

In the UK election campaign, however, journalists appeared more concerned with constructing balance when interpreting rules about impartiality, drawing on other parties to challenge the claims of political leaders.

Without interviewing journalists or editors, researchers cannot establish whether this was due to external influences, such as the greater party-political pressure they may receive when reporting domestic rather than foreign news issues.

In the researchers' view, the differences between the @BBC’s domestic & foreign coverage of elections were not *only* influenced by the greater scrutiny they would have received in their UK coverage.

The editorial construction of US and UK coverage articles would have been influenced by the closer relationships which journalists have with domestic rather than foreign political actors.

For example, UK journalists would have more frequent contact & access to better-established relationships with UK party communications teams than US counterparts.

This would facilitate a greater supply of “information subsidies” which help shape the construction of stories and perhaps explains why more UK than US leaders and parties were quoted in domestic election coverage.

This sociological influence and the domestic pressure to report impartially also helps explain specific instances where US and UK election coverage was different. For example, Trump’s egregious claims about Biden’s mental acuity were reported without any journalistic challenge.

It may be the case that the sheer volume of correctives required of Trump carried concerns of an appearance of bias and therefore ignoring claims of lower perceived importance, or perhaps credibility, was perceived as restoring some balance.

The @BBC's editorial guidelines state that due impartiality should be employed throughout the organisation, but they acknowledge how it is achieved may vary, “depending on the format, output and platform”.

This study has revealed such variation.

This study has revealed such variation.

In broadcast news, a limited conception of the range of views (i.e. he-said-she-said) was given primacy.

This reinforces Wahl-Jorgensen et al.’s analysis of @BBCNews that argued an “impartiality-as-balance” approach shaped coverage.

journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.117…

This reinforces Wahl-Jorgensen et al.’s analysis of @BBCNews that argued an “impartiality-as-balance” approach shaped coverage.

journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.117…

The @BBC’s Reality Check meanwhile drew on a far greater range of perspectives and offered an evaluation of the weight of those range of views. BBC news online coverage was typically somewhere in-between—offering a range of views with less consideration of their relative weight.

The pull towards the perhaps perceived safety of "she-said-he-said" in broadcast reporting particularly is possibly a reflection of its more prominent status, with coverage scrutinised more closely by the public and politicians.

"He-said-she-said" is a long-established and comfortable form stretching back to the Reithian ideal discussed earlier. It is therefore more embedded in the construction of broadcast news than in newer digital platforms.

Reality Check was specifically designed to produce a form of news that would help to counter #misinformation.

It is a style of journalism which considers both the range & relative weight of opinions & thus a closer embodiment to the wagon wheel envisioned by Bridcut.

It is a style of journalism which considers both the range & relative weight of opinions & thus a closer embodiment to the wagon wheel envisioned by Bridcut.

Yet, reporting in other parts of the BBC is still more accurately encapsulated by the seesaw.

The relevance of the research findings goes beyond our case study of the @BBC.

The relevance of the research findings goes beyond our case study of the @BBC.

Fact-checking journalism has risen in prominence in recent years, an implicit acknowledgement that the "he-said-she-said" approach to reporting does not work effectively if one, or perhaps both sides, regularly make dubious or false claims (Cushion et al. Citation, 2022).

The previously reliable employment of opinion balance is perhaps now an impartiality marker mitigated by the (un)reliability of the sources of information.

Moreover, recent research about how audiences believe #misinformation should be countered by broadcasters has demonstrated there is strong support in favour of more fact-checking style journalism.

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.108…

More finely tuned studies are needed to understand how journalists apply concepts about balance & impartiality in political reporting.

This study went beyond analysing coverage at a macro level (story) by assessing reporting on a micro level (political claim), establishing whether a claim was present, if it was challenged or not, and how explicitly it was corrected within a news item.

The authors of this research encourage journalism scholars to more creatively fine tune studies that empirically reveal editorial choices in how impartiality is constructed across different media platforms and online sites.

A follow-up qualitative analysis, in this respect, would likely reveal more nuanced differences than those which could be captured at the scale of data here.

There were several instances in the sample where the same claim covered across the different media was coded as an Explicit Corrective Interaction, yet the language used in broadcast seemed much softer than that online, which in turn was softer than that used on Reality Check.

The study was deliberately designed to capture data at election periods as these are the periods of perhaps greatest importance in terms of possible

democratic consequence, and the time when media receive extra scrutiny for impartiality and balance.

democratic consequence, and the time when media receive extra scrutiny for impartiality and balance.

There is no strong reason to believe that findings for a non-election period would be much different, but it is acknowledged that the strength of findings could differ; lesser scrutiny may embolden more @BBC journalists to embed greater & stronger fact-checking practices.

This case study questioned how the concept of impartiality was operationalised by the @BBC, finding efforts to achieve due impartiality altered depending on the domestic or international context of the story, the politician involved in the story, & the platform producing it.

Viewed from this perspective, impartiality appears to be a fluid rather than fixed concept and applied differently according to the political context.

Impartiality was even interpreted differently between and within departments of the same (@BBC) News organisation.

Impartiality was even interpreted differently between and within departments of the same (@BBC) News organisation.

More empirical inquiries about how impartiality is interpreted are required.

The paradigm of “impartiality-as-balance” is still often the default position of journalism, evidenced here as being employed particularly in broadcast, & more in a domestic than international setting.

The paradigm of “impartiality-as-balance” is still often the default position of journalism, evidenced here as being employed particularly in broadcast, & more in a domestic than international setting.

At a time characterised by misinformation, rather than simply reporting what "she-said" & what "he-said", journalists must reflect the relative weight of evidence when reporting political claims, & apply more robust scrutiny & interrogation about what "she said" & what "he said".

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh