Both @Neil_Irwin and @ObsoleteDogma have highlighted the 2015-16 slowdown in the US economy in recent columns. 100% agree that there was an under-covered mini-recession then, one that hit manufacturing and commodity intensive regions hard.

(thread)

nytimes.com/2018/09/29/ups…

(thread)

nytimes.com/2018/09/29/ups…

. @Neil_Irwin starts his story in 2015, and focuses on the impact that the commodity slump (and China's slowdown) had on investment in key sectors.

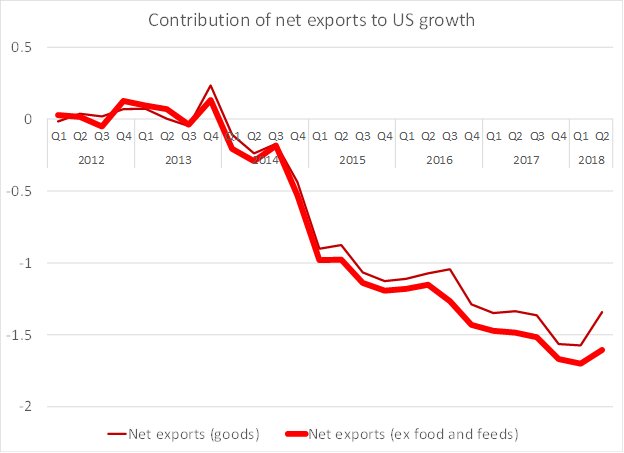

I would start in 2014, and put more emphasis on the dollar, and the impact of a stronger dollar on net exports.

I would start in 2014, and put more emphasis on the dollar, and the impact of a stronger dollar on net exports.

Dollar strength - which was primarily a function of monetary divergences among the G-3 (Fed signalling expected rate hikes, ECB doing QE, BoJ doing more QE) rather than commodity currency moves - knocked about a point off US growth in late 14 and early 15.

In broad terms the drag from net exports then was comparable to the drag at the peak of the China shock (a rise of around 1 pp in imports, not matched by a // rise in exports). but it got a lot less coverage and attention at the time.

and the impact on US trade from the stronger dollar then got far less attention that the "trade war" now - even though the drag on net exports from a stronger dollar is comparable to high end estimates of the impact of Trump's 2018/19 tariffs.

think there were a couple of reasons for this: the trade deficit didn't move, as falling oil prices led to a fall in nominal oil imports that offset the rise in the non-oil deficit, and the strong dollar impacted exports rather than imports, and that creates less drama.

But weakness in exports -and my own work has highlighted that the dollar contributed to this, as the US took more of the burden of weaker global demand than Europe and Japan - added to the shock on "real" goods from weakness in investment.

Caterpillar is an important exporter. It saw a fall in domestic demand for its equipment, but also a fall in external demand. That added the blue collar stress that @ObsoleteDogma highlighted.

washingtonpost.com/business/2018/…

washingtonpost.com/business/2018/…

B/c of the strong dollar, and b/c the US had a bigger oil sector and thus experienced a negative shock to investment when oil fell, by 16 if not before the gap between monetary policies among the G-3 was bigger than the gap in actual economic performance ...

The Fed was right to pause after China's August 2015 depreciation scared the world - US conditions called for it. But much of the damage had already been done. The 15 China scare was as much a part a function of the 14 rise in the dollar as domestic Chinese conditions ...

With global trade slowing (because of a fall in investment in commodities, and a necessary cutback in imports in the oil exporters when oil fell more than b/c of protectionism) China didn't think it could follow the dollar up when its own economy was weak, and choose to devalue

Consistent with Neil Irwin's argument, the 14-15 dollar appreciation and resulting mini recession is associated with a rather fundamental break in global financial flows as well.

cfr.org/blog/mapping-c…

cfr.org/blog/mapping-c…

That's when global reserve growth stalls/ reverses, and when foreign demand for treasuries dries up.

Paradoxically, the dollar's rally meant reduced foreign demand for Treasuries, as it was driven by private investors who preferred agencies and corporate bonds ...

Paradoxically, the dollar's rally meant reduced foreign demand for Treasuries, as it was driven by private investors who preferred agencies and corporate bonds ...

That's my take at least. Glad the impact of moves in the global economy in 14 and 15 on the US economy are getting more attention. I have long thought that the slump in exports and investment in 15-16 played a small role in the 16 election ...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh