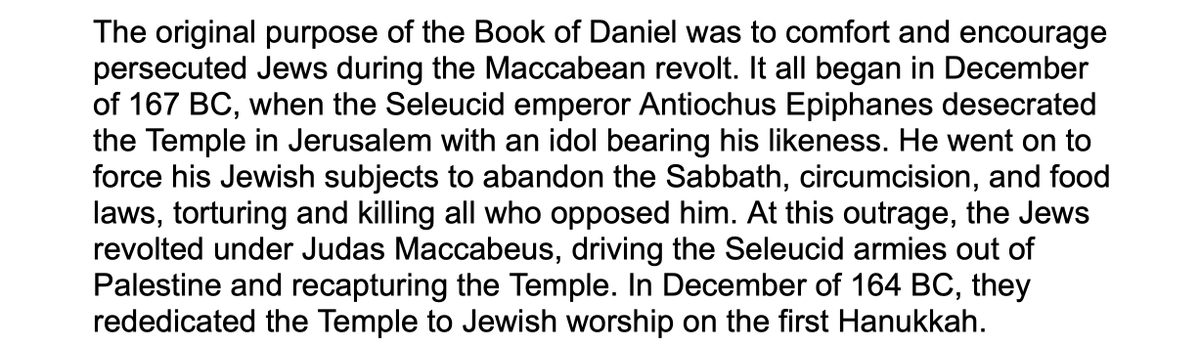

Until recent times, the majority of Biblical commentators took the book of Daniel to represent the memoirs of a 6th cent. exiled prophet (named Daniel).

In recent times, however, that situation has more or less reversed.

First though, a word or two on what the Maccabean Hypothesis (hereafter ‘the MH’) actually asserts.

It is not in fact a collection of visions/prophecies revealed to a 6th cent. exile; it is the work of a 2nd cent. Israelite...

Daniel is decidedly inaccurate when he writes about the 6th cent. BC,

becomes progressively more accurate as time goes on,

all of which is neatly explained by the Macc. Hypothesis.

Advocates of the MH also advance other lines of evidence for their view. These include:

🔹 after-the-event ‘prophecies’ and four-empire schemas elsewhere in the ANE,

🔹 Daniel-like documents in the Dead Sea Scrolls (e.g., Pseudo-Daniel), and

As such, advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis are able to mount a persuasive cumulative case in favour of their view.

yet is exactly the kind of book a 2nd cent. author would write.

So then, what can be said by way of response to the Maccabean Hypothesis?

Many things.

…and how the Maccabean Daniel came to be referred to as ‘Daniel the Prophet’ at Qumran (cp. Koch 1985:122).

a] Antiochus will conquer Egypt (11.42–43),

b] Antiochus will perish soon afterwards somewhere in Israel (11.44–45), and

c] finally, the Messianic era will begin (12.1ff.).

Antiochus never conquered Egypt,

nor did he die in Israel.

Advocates of the Macc. Hypothesis are, of course, aware of these facts, but their responses strike me as rather weak.

‘That Daniel’s expectation does not correspond to the known data of history’, Hartman says, ‘in no way detracts from his confident faith and sure hope in God’s control over tyrants such as Antiochus Epiphanes’ (Hartman 1979:303).

But the test of a prophet is not his level of confidence; it is the accuracy of his prophecies (Deut. 18.20–22)—a test which the Maccabean Daniel dramatically failed.

Daniel was, in the words of H. H. Rowley, ‘a man with an imperfect knowledge of past history and exaggerated hopes for the future’ (Rowley 1959:180–182).

Ch. 2’s theology is simple, explicit, and profound.

God’s people can know with certainty what is hidden to the world’s wisest men.

Why? Because the God of Israel controls the future and speaks to his people (2.10–11, 27–28).

They ‘do not reside with flesh and blood’ and hence cannot help their followers (2.11).

As a result, the wise men are unaware of the contents of the king’s dream, as they are of Babylon’s imminent fall.

That the Maccabean ‘Daniel’ would have had the nerve to append his ‘prophecies’ to such stories is hard to imagine.

After all, the Maccabean Daniel was in the same boat as Babylon’s wise men.

God had not revealed the future to any of Judah’s 6th cent. exiles (hence Daniel 2–6’s material had to be taken from legends),

As such, the theology of Daniel 2–6 would hardly have sat comfortably alongside the Maccabean Daniel’s.

Indeed, it would have invalidated his status as a prophet,

To explain Daniel’s canonisation, we would need to posit the existence of a (2nd cent.?) community of people who viewed Daniel as Scripture and yet disagreed with its theology.

On the Macc. Hypothesis, Daniel was not a ‘prophet’ in the traditional sense of the word,

Daniel was merely a ‘sage’ who had sought to guess what would happen in the near future on the basis of his (rather hazy) knowledge of history.

That Antiochus would conquer Egypt (let alone Libya and Ethiopia) was practically unthinkable in 165 BC.

Antiochus was a spent force.

Meanwhile, Egypt was a fully paid-up member of the protectorate of Rome (the day’s undisputed superpower).

Antiochus was about as likely to conquer Egypt as Syria are to conquer Russia next year.

#NotAPrediction

Consider, for instance, Daniel’s reference to Belshazzar (Babylon’s vice-regent) as /malkā/ = ‘the king’.

Consider, for instance, the text of Dan. 9.27.

which is generally thought to have been inaugurated at some time between Sep. 175 BC and Apr. 172 BC (cp. Schwartz 2008:231 on 2 Macc. 4)

Similar issues surround 9.26’s reference to the death of ‘an anointed one’ (Messiah).

It seems to depend more on one’s presuppositions than on the evidence involved.

As we’ve seen, the Maccabean Hypothesis isn’t merely a statement about when Daniel was composed;

On the Macc. Hypothesis, the reason why Daniel puts pen to paper is to bolster the faithful in the days of the Maccabees.

Towner (another MH-advocate) concurs.

Below, I’ll outline two of them.

(1). Daniel has no reason to include an independent Median empire in his four-empire schema.

It’s a depiction of the major influences on Judah’s history over the years—a category to which ‘Media’ doesn’t belong.

To depict Judah’s history in terms of Babylon, Media, and Persia would, therefore, be an unusual course of action,

As E. Lucas says, ‘The inclusion of Media (among Daniel’s empires) is odd since the Medes never gained control of Babylon or Judah’ (Lucas 1989:192).

Every time ‘Media’ is mentioned in the book of Daniel, it is mentioned in the context of *Medo-Persia* (5.28, 6.8, 12, 15, 8.20).

Of course, advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis are not insensitive to these considerations, and have sought to account for them in various ways.

But such ‘explanations’ do not explain a great deal.

The two-armed torso aligns with the two-sided bear and the two-horned ram;

the four-headed leopard aligns with the four-horned goat;

and the ten-toed feet align with the ten-horned beast.

The Medo-Persian empire was composed of two sub-empires (the Medes and the Persians),

and the Greek empire splintered into four sub-empires.

The two-sided bear is no longer aligned with the two-horned ram;

the four-headed leopard is no longer aligned with the four-horned goat;

Daniel’s visions are also out of sync with *history*.

The independent Median empire didn’t consist of two distinct parts;

and the Greek empire was never ruled by ten co-regents.

What’s gone wrong isn’t hard to see.

and the four-headed leopard has been shifted out of alignment with the four-horned goat.

It’s clearly not the way Daniel’s visions are supposed to be understood.

In sum, then, the Maccabean Hypothesis fails (at least in my view) to explain what we find before us in the book of Daniel.

In historical terms, it struggles to explain Daniel’s status as Scripture (as well as Daniel’s wild prediction of Egypt’s fall).

In theological terms, it leads to incoherence.

Indeed, the traditional view of Daniel has difficulties of its own.

Ultimately, the book of Daniel invites us to approach it with a particular attitude of heart.

THE END

Note: The pdf might not immediately be viewable, but should be downloadable.

academia.edu/41459263/