*Caution non-peer reviewed preprint* There have been many anecdotes about prolonged #COVID19 symptoms but little systematic data collection. Here, results from prospective study of 152 patients @nyulangone hospitalized with #COVID19. /1 medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

tl;dr results: 113/152 (74%) reported persistent shortness of breath 30-40 days after discharge. 13.5% still needed oxygen. Overall physical health was rated 44/100 after vs 54 before - full standard deviation drop vs national norms. Mental health score dropped from 54 to 47.

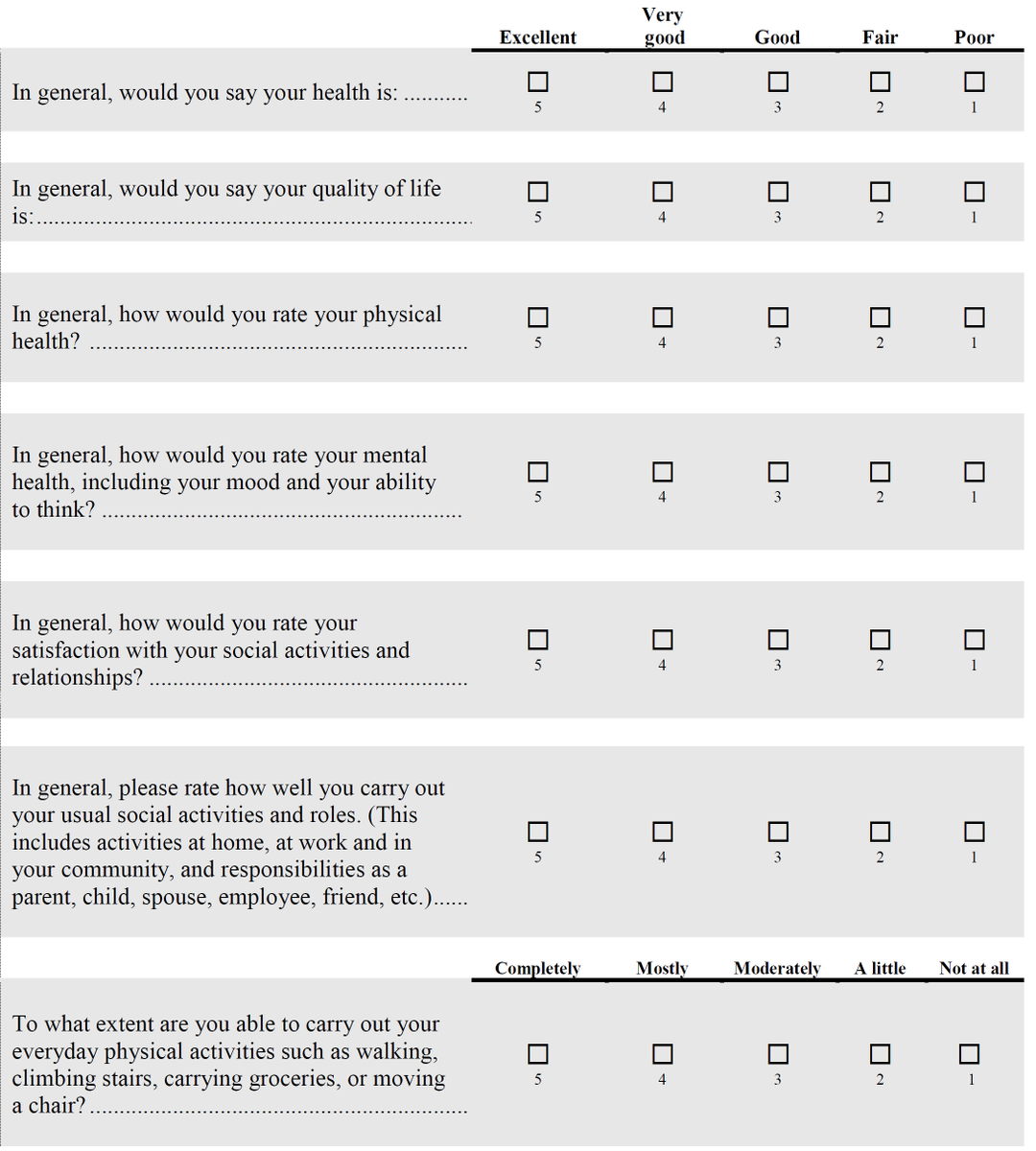

Details: We enrolled 152 (38% of eligible) patients; all had lab confirmed #COVID19 & needed at least 6L oxygen during hospitalization; each completed the PROMIS 10 global health questionnaire and the PROMIS dyspnea scale, answering for current and pre-COVID state.

Patients were median age 62, 44% white, 77% English speaking, 83% with at least one chronic condition. Median length of stay 18 days: so, interviewed at ~7-10 weeks after symptom onset. Here's the dyspnea scale.

Note that we included only people who were quite sick during hospitalization, BUT, we also excluded those too frail to answer, those rehospitalized, those with cognitive impairment etc, all of whom likely had even worse symptoms.

A recent report from Italy of discharged patients at a similar time frame in disease course shows similar results, through focused on somatic symptoms not function. jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/…

By contrast this preprint of non-hospitalized patients in Atlanta shows lower symptom severity 30 days after symptom onset medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

And there have been non-systematic assessments of persistent symptoms like this preprint, but of course skewed towards those who choose to self report. medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

Also, tagging those of our stellar team who are on twitter @KHochmanMD @CBlaumMD @JChodoshMD @kira_garry

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh