THREAD: ‘If they do these things in a green tree…’ (Revised)

I’ve recently become quite fascinated by Jesus’ trio of riddles/statements in Luke 23.27–31.

If you feel inclined, please join me for a brief consideration of them.

I’ve recently become quite fascinated by Jesus’ trio of riddles/statements in Luke 23.27–31.

If you feel inclined, please join me for a brief consideration of them.

As Jesus is led away to be crucified, he speaks to the people around him about what will soon come to pass in Jerusalem (23.27–31).

Jesus’ speech consists of a mere 62 words. Interwoven within it, however, are allusions to at least Song of Solomon 3, Ezekiel 17, and Hosea 10.

Jesus’ speech consists of a mere 62 words. Interwoven within it, however, are allusions to at least Song of Solomon 3, Ezekiel 17, and Hosea 10.

That Jesus has these particular texts in mind isn’t too hard to demonstrate.

Only one book in the OT mentions ‘the daughters of Jerusalem’, which is the Song of Solomon;

Jesus’ allusion to Hosea is (almost) a direct quotation;

Only one book in the OT mentions ‘the daughters of Jerusalem’, which is the Song of Solomon;

Jesus’ allusion to Hosea is (almost) a direct quotation;

and only one book in the OT juxtaposes the images of green and dry trees, which is Ezekiel.

Furthermore: all three texts are connected by common imagery—in particular, their descriptions of vines and marriages;

Furthermore: all three texts are connected by common imagery—in particular, their descriptions of vines and marriages;

Jesus doesn’t allude to any of these texts elsewhere (indeed, the entirety of 23.27–31 is unique to Luke);

and, as we’ll see, the texts in question together form a rich interpretative backdrop for Luke’s passion narrative,

and, as we’ll see, the texts in question together form a rich interpretative backdrop for Luke’s passion narrative,

...which is roughly schematised below (to be explained below with the aid of sentences).

First, however, let’s briefly zoom out.

First, however, let’s briefly zoom out.

THE SHAPE OF LUKE’S GOSPEL.

That the bookends of Luke’s Gospel resonate with one another is well known.

For instance, in both bookends, we encounter a Messiah who disappears for three days at the time of the Passover,

That the bookends of Luke’s Gospel resonate with one another is well known.

For instance, in both bookends, we encounter a Messiah who disappears for three days at the time of the Passover,

a surprised couple on the road who suddenly (and unexpectedly) become aware of their Messiah’s presence/absence,

and a priestly figure who lifts his hands heavenwards, blesses those present, and departs in peace (cp. 2.27–29, 24.50ff. w. 2.38).

and a priestly figure who lifts his hands heavenwards, blesses those present, and departs in peace (cp. 2.27–29, 24.50ff. w. 2.38).

These resonances have caused some people, like a well-known Shulamite woman, to run around Luke’s Gospel in search of a grand chiasmus,

if possible with the Mount of Transfiguration at its centre.

But while such people have sought, they have not, to my knowledge, found.

if possible with the Mount of Transfiguration at its centre.

But while such people have sought, they have not, to my knowledge, found.

What can be found, I submit, are further contact-points with the aforementioned Shulamite’s story.

THE SONG OF SOLOMON

Certain features of Luke’s bookends are curiously resonant of the Song of Solomon. Among other things, we read about:

Certain features of Luke’s bookends are curiously resonant of the Song of Solomon. Among other things, we read about:

These images flicker in the background of Luke’s narrative as Jesus closes in on Jerusalem,

and, in 23.28, Jesus brings them to the foreground by means of his reference to the women around him as ‘daughters of Jerusalem’—a phrase found seven times in the Song of Solomon...

and, in 23.28, Jesus brings them to the foreground by means of his reference to the women around him as ‘daughters of Jerusalem’—a phrase found seven times in the Song of Solomon...

...and once in the NT, here in the Gospel of Luke.

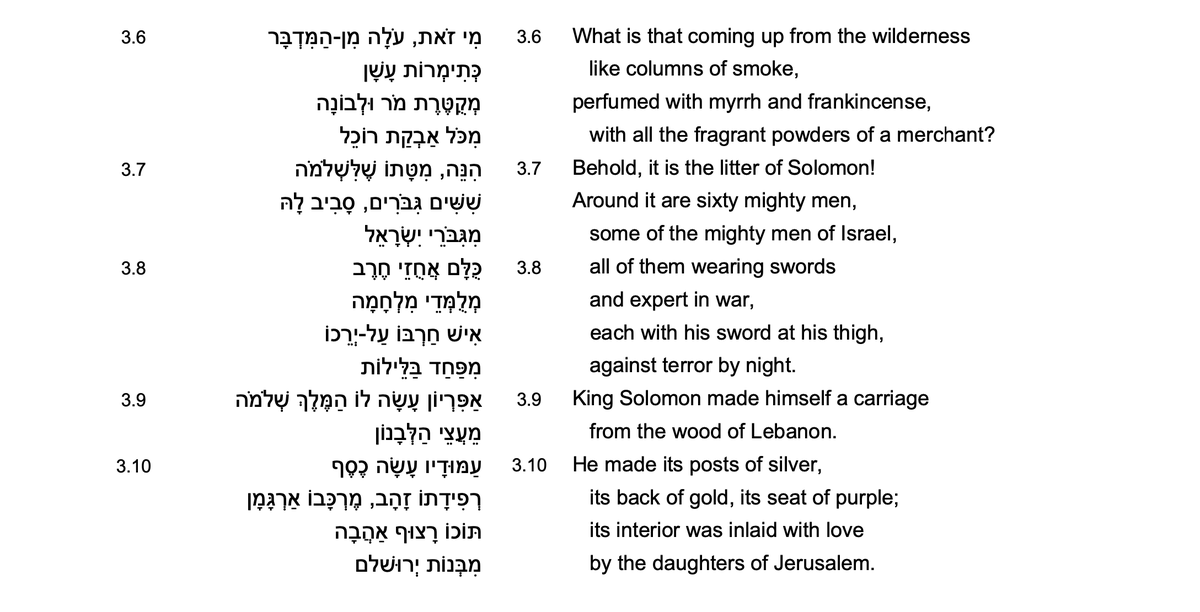

As we’ll see, particularly relevant to Jesus’ situation in 23.27–31 is the Song’s central reference to the daughters of Jerusalem, namely the text of SoS. 3.6–11.

As we’ll see, particularly relevant to Jesus’ situation in 23.27–31 is the Song’s central reference to the daughters of Jerusalem, namely the text of SoS. 3.6–11.

Jesus wants us to see what is about to transpire in Jerusalem in light of King Solomon’s arrival on the day of his marriage,

since beyond the immediate shame and isolation of the cross lies glory and reconciliation—an act where YHWH’s king is united to his bride.

since beyond the immediate shame and isolation of the cross lies glory and reconciliation—an act where YHWH’s king is united to his bride.

To put the point another way, the text of Luke 23 describes how Jesus is treated in Jerusalem (as a matter of historical fact),

while Jesus’ allusion to the Song of Solomon depicts: a] how Jesus should have been treated,

while Jesus’ allusion to the Song of Solomon depicts: a] how Jesus should have been treated,

and b] the divinely-ordained significance of what transpires there.

As a result, our text and the text of SoS. 3.6–11 describe scenes which are in some respects similar yet in others vastly different.

Below is a selection of some of the relevant similarities and differences:

As a result, our text and the text of SoS. 3.6–11 describe scenes which are in some respects similar yet in others vastly different.

Below is a selection of some of the relevant similarities and differences:

«Similarity #1»: Both Solomon and Jesus arrive in Jerusalem at the end of a long journey.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon approaches the city from the wilderness, surrounded by highly-trained warriors men (מְלֻמְּדִּים),...

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon approaches the city from the wilderness, surrounded by highly-trained warriors men (מְלֻמְּדִּים),...

...Jesus is led out of the city to the wilderness, abandoned by his disciples (תלמידים). And, while the purpose of Solomon’s armed guard is to protect him from ‘the terrors of the night’, the purpose of Jesus’ is to expose him to them (cp. 22.53).

«Similarity #2»: Both Solomon and Jesus’s female onlookers initially fail to recognise them.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s bride-to-be fails to recognise him because she first meets him as a shepherd and doesn’t expect him to appear accompanied by a royal entourage,...

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s bride-to-be fails to recognise him because she first meets him as a shepherd and doesn’t expect him to appear accompanied by a royal entourage,...

...Jesus’ onlookers fail to appreciate the nature of Luke 23’s events (and hence weep) because they expect their Messiah to come as a king rather than lay his life down as a ‘good shepherd’.

«Similarity #3»: Both Solomon and Jesus are surrounded by ‘clouds’.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon is surrounded by clouds of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and frankincense, Jesus is surrounded by a ‘cloud’ of false witnesses (whose thoughts are far from sweet),...

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon is surrounded by clouds of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and frankincense, Jesus is surrounded by a ‘cloud’ of false witnesses (whose thoughts are far from sweet),...

...and the ‘fragrance’ he wears has to do with his burial (24.1). His life will be offered up like frankincense, mixed with the bitterness of myrrh.

«Similarity #4»: Both Solomon and Jesus’ journeys involve a wooden structure studded with metal, on which each man is borne up.

«Similarity #4»: Both Solomon and Jesus’ journeys involve a wooden structure studded with metal, on which each man is borne up.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s wooden structure is a luxurious sedan chair, borne about by his men, Jesus’ is a cruel cross, carried by a lone individual, and is studded not with gold and silver, but with iron nails.

«Similarity #5»: Both Solomon and Jesus are associated with purple fabric.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s chariot is lined with purple fabric in recognition of his royalty, Jesus is clothed in purple in mockery of his, and is awarded the title ‘king of the Jews’ in jest.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s chariot is lined with purple fabric in recognition of his royalty, Jesus is clothed in purple in mockery of his, and is awarded the title ‘king of the Jews’ in jest.

«Similarity #6»: Both Solomon and Jesus are surrounded by ‘daughters of Jerusalem’.

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s daughters are invited to share in his ‘gladness’,...

«Difference»: Yet, while Solomon’s daughters are invited to share in his ‘gladness’,...

... Jesus invites the ‘daughters of Jerusalem’ to weep... in light of what will soon come to pass in their city (23.28), as Jesus himself has already done (19.41–44).

As can be seen, Solomon’s return to Jerusalem (SoS. 3.6–11) and Jesus’ exit from the same place (23.27–31) are tightly coupled together, not only thematically, but by means of Jesus’ own words.

Jesus wants us to view his crucifixion in light of SoS. 3.6–11.

Jesus wants us to view his crucifixion in light of SoS. 3.6–11.

Beyond the shame of the cross lies glory and honour.

Beyond the isolation of the cross is the union of a man and his bride.

And beyond the death of the cross is life immortal.

Beyond the isolation of the cross is the union of a man and his bride.

And beyond the death of the cross is life immortal.

For that reason, Jesus tells the mothers in Israel around him not to weep on his behalf,

but to weep at the thought of what will befall their children (i.e., the generation to come),

which Jesus goes on to describe in more detail in 23.29–30.

but to weep at the thought of what will befall their children (i.e., the generation to come),

which Jesus goes on to describe in more detail in 23.29–30.

HOSEA’S CURSE

In 23.29–30, Jesus quotes Hosea 10.8.

Just as Jesus’ mention of the ‘daughters of Jerusalem’ alludes not just to an isolated verse, but to a whole section of Scripture, so too does Jesus’ reference to Hos. 10.8.

In 23.29–30, Jesus quotes Hosea 10.8.

Just as Jesus’ mention of the ‘daughters of Jerusalem’ alludes not just to an isolated verse, but to a whole section of Scripture, so too does Jesus’ reference to Hos. 10.8.

Consider Hosea’s portrayal of Israel’s condition.

Israel has betrayed her husband (Hos. 2) and rebelled against her God (Hos. 8.14).

Israel has betrayed her husband (Hos. 2) and rebelled against her God (Hos. 8.14).

She is hence depicted as a once-fruitful vine which has now dried up (Hos. 9.10, 16, 10.1)—an image which anticipates Jesus’ question in 23.31 (‘What will happen when the green tree is dry?’).

Her people have even uttered the awful words, ‘We have no king’ (Hos. 10.3)—words which are explicitly attributed to the Jewish leaders in John 19 and whose truth is implicit in Luke 23 (where the Jews deliver God’s Messiah to the Romans because he refuses to submit to Caesar).

Judgment is, therefore, unavoidable.

The days will come when Israel’s mothers will be cruelly bereaved,

which will make life more bearable for those who are barren than for mothers (Hos. 9.12, 14, 16).

The days will come when Israel’s mothers will be cruelly bereaved,

which will make life more bearable for those who are barren than for mothers (Hos. 9.12, 14, 16).

As judgment closes in, the Israelites will ask the mountains to fall on them—that is to say, they will seek death (cp. Rev. 9.6)—,

though in vain (Hos. 10.8).

Israel’s king will be cut off at dawn (!) (Hos. 10.15) (a statement we’ll consider the significance of later),...

though in vain (Hos. 10.8).

Israel’s king will be cut off at dawn (!) (Hos. 10.15) (a statement we’ll consider the significance of later),...

...and Israel will be cast out into the wilderness of the nations (Hos. 9.17).

Many of these details are already present in the background of Luke’s narrative (especially given Jesus’ references to fruitless vines: 13.6–7, 20.9ff.),

and, in 23.29, Jesus brings them to the foreground by his quotation of Hosea 10.8.

and, in 23.29, Jesus brings them to the foreground by his quotation of Hosea 10.8.

As Jesus speaks to the crowds around him, Israel’s judgement is nigh. What the Assyrians did in Hosea’s day, the Romans will do in Jesus’ day—or, more precisely, in the days of the next generation (cp. 23.29–30).

Like the dry, disowned bride of Hosea 2, Israel will be cast out and left to wander the nations (cp. Hos. 9–10).

As such, Hos. 9–10 describes an inversion of the Song of Solomon.

As such, Hos. 9–10 describes an inversion of the Song of Solomon.

Whereas Solomon’s bride-to-be has an unkempt vineyard and comes to enjoy in fruitful vineyards by virtue of her marriage to the king (SoS. 1.6, 2.10–15), Hosea’s Israel is disowned by her husband (YHWH) and her vineyards hence waste away (Hos. 2).

EZEKIEL’S VINES/TREES

We hence come to Jesus’ statement in 23.31: ‘If they do these things when the wood/tree (ξύλον) is green, what will happen when it is dry?’

We hence come to Jesus’ statement in 23.31: ‘If they do these things when the wood/tree (ξύλον) is green, what will happen when it is dry?’

The sense of Jesus’ statement in Luke 23.31 isn’t immediately apparent.

Although it sounds like a proverb/idiom, explorations of relevant literature haven’t shed much light on it.

More informative is the statement of a different son of man: the prophecy of Ezekiel 17.

Although it sounds like a proverb/idiom, explorations of relevant literature haven’t shed much light on it.

More informative is the statement of a different son of man: the prophecy of Ezekiel 17.

At the outset of Ezekiel 17, Israel is given a new start. She begins her days under Babylonian’s rule as a fruitful vine. Yet, sadly, she doesn’t remain fruitful (Ezek. 17.7, 11ff.).

Although God has assigned Israel to the overlordship of Babylon, Israel prefers her old overlord (Egypt),

and, like Hosea 2’s wife, she seeks to return to him (per Ezek. 16).

and, like Hosea 2’s wife, she seeks to return to him (per Ezek. 16).

Courtesy of Babylon, therefore, Israel will be uprooted and left to die (Ezek. 17.9).

The tall tree will be brought low, and the green tree will dry up (Ezek. 17.24)—another inversion of the Song of Solomon.

The tall tree will be brought low, and the green tree will dry up (Ezek. 17.24)—another inversion of the Song of Solomon.

Again, many of these details are already present in the background of Luke’s narrative (especially given Jesus’ repeated references to the imminent humiliation of those who have raised themselves up in Judah: e.g., 14.11, 18.14),...

...and, in 23.31, Jesus brings them to the foreground by means of his allusion to Ezekiel 17.

What the Babylonians did to the Jews of Ezekiel’s day who rebelled against their rule, the Romans will do in the days of the generation to come (and rightly so).

What the Babylonians did to the Jews of Ezekiel’s day who rebelled against their rule, the Romans will do in the days of the generation to come (and rightly so).

And, given what the Jews are about to do to Jesus when ‘the wood is green’—i.e., before Israel’s time of judgment has come—, things will be unbearable when Israel’s time does finally come, i.e., when Israel is dry and ready to be burned (23.31).

In other words, given the Jews’ merciless treatment of Jesus, the Jews cannot expect to be shown mercy themselves.

Also relevant is the text of Ezek. 20.47,...

Also relevant is the text of Ezek. 20.47,...

...where Ezekiel incorporates the image of fire into the scene described in 17.24 in order to highlight the aptness of dry wood to be burned.

A dried out vine, Israel will be fit only to be burnt (cp. Ezek. 15). And burnt she will be.

A dried out vine, Israel will be fit only to be burnt (cp. Ezek. 15). And burnt she will be.

In the 1st cent. AD, the three phenomena described in SoS. 8.6 will come together in a single historical era:

a love as strong as death, a jealousy as merciless as the grave, and the very flame of YHWH.

a love as strong as death, a jealousy as merciless as the grave, and the very flame of YHWH.

JESUS’ PORTRAYAL OF HIS DEATH

With the above points in mind, further layers of our text can be unravelled.

The first is what it tells us about Jesus’ portrayal of his death.

With the above points in mind, further layers of our text can be unravelled.

The first is what it tells us about Jesus’ portrayal of his death.

Jesus’ statements couple together his and his people’s fates.

Both Jesus and his people will undergo a fate worthy of lament. (Tears are shed for Jesus, though Jesus says they are best be spared for a later generation.)

Both Jesus and his people will undergo a fate worthy of lament. (Tears are shed for Jesus, though Jesus says they are best be spared for a later generation.)

And both Jesus and his people will be exposed to God’s fire of judgment.

As such, Jesus connects his death with wrath and judgment.

As such, Jesus connects his death with wrath and judgment.

Additional information is provided by Jesus’ association of his death with ‘greenness’,

which is significant for at least two reasons.

which is significant for at least two reasons.

First, since green trees aren’t apt to burn, it portrays Jesus’ death as exceptional in some way.

What would be apt for the dry tree to undergo is undergone by the green tree.

What would be apt for the dry tree to undergo is undergone by the green tree.

Second, since Israel’s time of ‘dryness’ is yet to come, it portrays Jesus’ death as somehow ‘inaugural’ or ‘ahead of time’.

In Jesus’ day, the land is still green, yet Jesus tastes the dryness of a day to come.

As John Nolland says (by way of summary):

In Jesus’ day, the land is still green, yet Jesus tastes the dryness of a day to come.

As John Nolland says (by way of summary):

Jesus doesn’t view himself as ‘a natural object of the disaster…about to engulf his people in judgment of their sin’;

rather, ‘Jesus goes to the cross at his Father’s behest,…as his destined mode of participation in his people’s disaster’.

rather, ‘Jesus goes to the cross at his Father’s behest,…as his destined mode of participation in his people’s disaster’.

As such, Jesus portrays his death as inherently ‘penal’.

While those who rebel against Rome in 70 AD will get what they deserve, Jesus will be subjected to a fate he does not deserve,...

While those who rebel against Rome in 70 AD will get what they deserve, Jesus will be subjected to a fate he does not deserve,...

...as one of Luke’s criminals points out. (‘We’re getting what our deeds deserve, yet this man has done nothing wrong!’: 23.41.)

Jesus, the fruitful vine of Hosea 10, will be treated like the withered vine of Ezekiel 17.

Jesus, the fruitful vine of Hosea 10, will be treated like the withered vine of Ezekiel 17.

That is not to say Jesus’ statements outline a full-orbed theory of penal substitutionary atonement.

The possibility of escape from the fiery judgment to come isn’t mentioned in 23.28–31, since Israel’s judgment is by now unavoidable.

The possibility of escape from the fiery judgment to come isn’t mentioned in 23.28–31, since Israel’s judgment is by now unavoidable.

As such, 23.28–31 doesn’t portray Jesus’ death as *substitutionary*. (Jesus and Israel alike are subjected to fire.)

Yet Jesus’ continued dialogue/interaction with those around him introduces the possibility of salvation.

Yet Jesus’ continued dialogue/interaction with those around him introduces the possibility of salvation.

Against the backdrop of his baptism of fire (23.31), Jesus asks God to spare his executioners (23.34);

meanwhile, the criminal crucified alongside Jesus—who says he and Jesus are ‘under the same sentence of condemnation’ (κρίμα)—refers to God’s kingdom as an imminent reality (23.40–42),

and, in response, Jesus promises him a place in it (23.43).

and, in response, Jesus promises him a place in it (23.43).

As such, the kingdom inaugurated by Jesus’ death offers refuge from the judgment to come.

A related note of hope can be found in Ezekiel 17.

True, Judah’s tall trees will be brought low and her green trees made dry. Yet, at the same time, Judah’s ‘low trees’ will be raised up and her dry trees made to flourish (Ezek. 17.22–24) (cp. Luke 14.11, 18.14).

True, Judah’s tall trees will be brought low and her green trees made dry. Yet, at the same time, Judah’s ‘low trees’ will be raised up and her dry trees made to flourish (Ezek. 17.22–24) (cp. Luke 14.11, 18.14).

From a tender twig will grow forth a tree with great branches, in which the birds of the air will come to shelter (Ezek. 17.23)—the very image employed by Jesus to describe his kingdom (13.19),...

...the rise of which is announced soon after Jesus’ threat to uproot Israel’s vine (13.6–9).

As such, Jesus’ death has distinctly substitutionary elements.

As such, Jesus’ death has distinctly substitutionary elements.

Because Jesus has stood in Israel’s place and allowed the fire of YHWH to pass over him—and because, furthermore, Jesus has risen from the dead—, green shoots will grow in Israel in the aftermath of 70 AD’s fiery judgment.

In other words, because Jesus has passed through death, Israel may do likewise.

SUMMARY AND FINAL REFLECTIONS

As we’ve seen, Jesus’ speech in Luke 23.27–31 is built around three key OT allusions,

each of which brings out a particular aspect of what will come to pass in Jerusalem.

As we’ve seen, Jesus’ speech in Luke 23.27–31 is built around three key OT allusions,

each of which brings out a particular aspect of what will come to pass in Jerusalem.

Given the connection between these three texts, however, we should consider what can be gleaned from them when they’re viewed as an integrated unit.

The most instructive connection between our texts, I submit, is their descriptions of vines and marriages.

Both Hosea and Ezekiel describe a dried up vine and a broken marriage, which depict Israel’s (sorry) condition in Jesus’ day:

Both Hosea and Ezekiel describe a dried up vine and a broken marriage, which depict Israel’s (sorry) condition in Jesus’ day:

Israel is like an unfruitful vine, detached from her source of nourishment (YHWH) and fit only to be burned.

Yet Jesus frames these descriptions of Israel against the backdrop of the Song of Solomon, which describes a vine and a marriage in a very different state;

Yet Jesus frames these descriptions of Israel against the backdrop of the Song of Solomon, which describes a vine and a marriage in a very different state;

more precisely, it describes a newly-wed couple amidst Israel’s green hills and vineyards, which fills out Ezekiel 17’s note of hope.

Jesus has come to breathe new life into Israel:

to renew YHWH’s marriage to her (cp. Hos. 2.14ff., Ezek. 16.60),

Jesus has come to breathe new life into Israel:

to renew YHWH’s marriage to her (cp. Hos. 2.14ff., Ezek. 16.60),

to allow her to enjoy YHWH’s vineyards once again (20.9–16),

to grant Israel’s outcasts a place with him in ‘paradise’ (παράδεισος cp. Hebrew pardes = ‘a fruitful forest’!).

to grant Israel’s outcasts a place with him in ‘paradise’ (παράδεισος cp. Hebrew pardes = ‘a fruitful forest’!).

A schematised view of the interrelation between our texts is shown below,

which highlights the pivotal position of Jesus’ statements in Luke 23.28–31.

Israel find themselves at a crossroads, and are faced with two options: to go into exile or to live on in a new form.

which highlights the pivotal position of Jesus’ statements in Luke 23.28–31.

Israel find themselves at a crossroads, and are faced with two options: to go into exile or to live on in a new form.

Either way, however, before Israel’s curse can be undone, Jesus must pass through the veil of death.

As Jesus himself states, he must take on the role of Isaiah 53’s servant and be ‘numbered among the transgressors’ (22.37),

which is significant,

As Jesus himself states, he must take on the role of Isaiah 53’s servant and be ‘numbered among the transgressors’ (22.37),

which is significant,

since the text of Isaiah 54–56 describes the reversal of the very events described by Jesus in 23.28–31.

The barren are blessed (Isa. 54a), Israel’s marriage is restored (Isa. 54b), Israel’s mountains sing for joy (Isa. 55),

The barren are blessed (Isa. 54a), Israel’s marriage is restored (Isa. 54b), Israel’s mountains sing for joy (Isa. 55),

and her dry trees/eunuchs are granted an inheritance (Isa. 56).

First, however, the servant of Isaiah 53 must do his work.

Jesus must bear the judgment due to fall on the old Israel, which is what he does on the cross.

First, however, the servant of Isaiah 53 must do his work.

Jesus must bear the judgment due to fall on the old Israel, which is what he does on the cross.

He is delivered over to the instruments of God’s judgment (the Romans) and condemned to death by their representative.

On the cross, Jesus becomes thirsty.

Hosea’s ‘thorns and thistles’ take hold of him (cp. Matt. 27.29’s crown of thorns),...

On the cross, Jesus becomes thirsty.

Hosea’s ‘thorns and thistles’ take hold of him (cp. Matt. 27.29’s crown of thorns),...

...even as the flame of YHWH flickers in the background.

Jesus becomes the exiled king of Hosea 10.15, who is cut off as darkness descends, and the dry tree of Ezekiel 17.

And yet by the same token he becomes Israel’s husband, redeemer, and king.

Jesus becomes the exiled king of Hosea 10.15, who is cut off as darkness descends, and the dry tree of Ezekiel 17.

And yet by the same token he becomes Israel’s husband, redeemer, and king.

In the days and person of Jesus, a mass of OT prophecies reach their climax, which Jesus reveals by a trio of brilliantly chosen allusions, summed up in a mere 62 words.

THE END.

P.S. With thanks to @andrewperriman for a great blog post on the subject.

THE END.

P.S. With thanks to @andrewperriman for a great blog post on the subject.

P.P.S. Pdf available here: academia.edu/44226005/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh