An Indonesian Qur’an translation for women – does this mean a feminist translation? No. It means that, in a country with a market economy and a large urban Muslim middle class, publishers have discovered women… #qurantranslationoftheweek 🌏🇮🇩

…as a lucrative target group of bilingual Qur’an editions. The Qur’an has become a commodity and is marketed as such. There are some Indonesian Qur’an editions that target men as well, but the market for women is larger by several orders of magnitude.

One might think of a number of explanations. Possibly, publishers assume that women are more pious, or more interested in performing their piety through consumerism, or more interested in consumerism in general.

Or they implicitly target their non-gendered Qur’an editions at men who are treated as the invisible, “normal” gender while women are the visible exception that would need targeted marketing, with particular needs, desires and tastes.

What do publishers do to match the perceived desires and tastes in their Qur’an editions for women? Neither the text of the Arabic Qur’an, the mushaf, nor the translation they use are out of the ordinary.

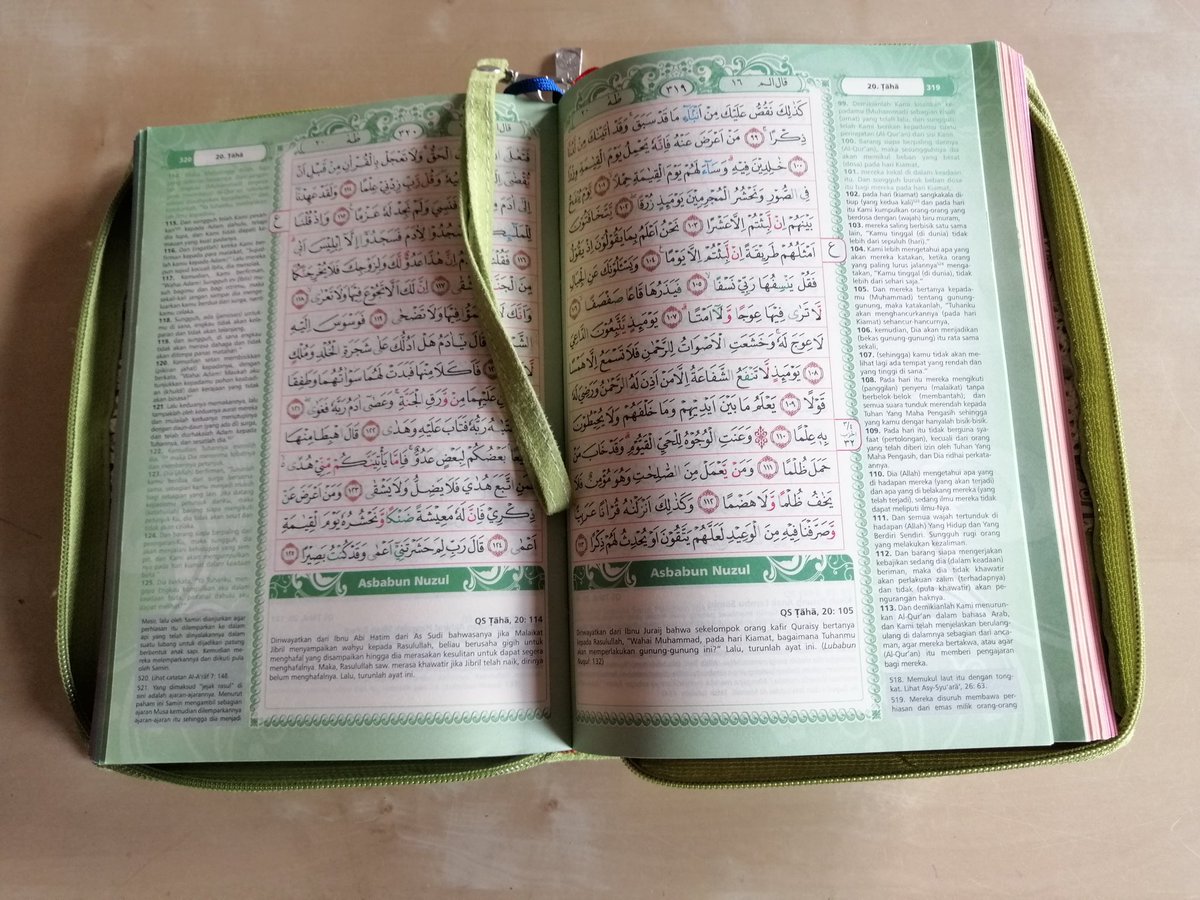

They rely on the government-approved Indonesian standard mushaf and on the translation by the Indonesian Ministry of Religion (gloqur.uni-freiburg.de/blog/qur2019an…).

The features that editors use to make their products appeal to women are in the attributes, physical presentation and paratexts. The covers come in a wide variety of colours and patterns, with lace and ornaments.

Pink, purple, pastel colours, and flower patterns are particularly common. The pages are coloured, frequently rainbow-coloured, again with a preference for pastel colours and lavish, flowery designs.

Many of the “women’s editions” have names, as is typical of Qur’an editions in Indonesia. They are called “Aisyah”, “Sabrina”, “Yasminah”, and even “Ummul Mukminin” (“Mother of believers”, an epithet of each of the prophet’s wives).

What women-specific content does the edition presented in this thread contain? Mainly, boxed paragraphs containing “hadiths about women and family”. These concern anything from marriage and menstruation to less gender-specific religious advice.

At the end, the book contains a twelve-page section on “practical fiqh for women”, summarizing rules about ritual washing, menstruation, ritual impurity, dress, conduct towards men, and the role of women in society and marriage.

All of the fiqh rules presented here project a socially conservative understanding of Islam according to which modesty, ritual purity and the role of housewife should be among women’s priorities.

They also tend to describe women’s roles, rights and duties predominantly in terms of their relationship towards men. The “Qur’an for women” thus encourages women to perform piety in a gender-specific manner and in a gender-segregated setting.

It targets women as a distinct type of believer with special interests and needs, which center on the family and on their relationship to men.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh