This is fantastic - really impressive set of questions and issues raised on the international approach to illicit financial flows. There's a lot to say so I'll thread the replies here, bit by bit...

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324712537267621889

1. Why did the MDGs overlook non-aid finance? This was by design: the MDGs were driven by aid donors, and were largely conceived of as ensuring better alignment of donors and recipient states - setting common goals so aid would deliver more.

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324739437343944705?s=20

Here's Sakiko Fukuda-Parr on this point - whereas by 2015, the aid focus was widely understood as a central flaw in the MDGs, so the aim of the Sustainable Development Goals was to ensure much broader ownership & applying to countries at all income levels

researchgate.net/publication/29…

researchgate.net/publication/29…

And hence SDG 17, which is the start of the delivery goals, begins with 17.1: TAX, as the primary 'means of implementation' - aid is now firmly in its place (secondary at most) sdgcompass.org/sdgs/sdg-17/

2. Was there a backlash against the IFFs target because OECD leaders are participants/beneficiaries? Great question. We may never know for certain, but we can speculate that this wasn't a *direct* cause, for a couple of reasons...

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324739737207345166?s=20

First and foremost, the opposition to SDG 16.4 centred not on the offshore asset or anonymous company aspects - which are almost entirely those in which OECD politicians have been revealed to have a role of one sort or another. Instead, opposition aimed to exclude corporate tax.

But it's clear that OECD leaders are indirectly at least a firm part of the system that generates the opposition. The tendency to see 'their' multinationals as national champions; and the close circles of elites which include politicians, business leaders & professional advisers.

Was it easier for the business lobby and big four accounting firms to get the ear of OECD politicians, to argue for a reinterpretation of illicit financial flows in SDG 16.4, than it was for #taxjustice advocates to put the counterarguments? Damn right.

3. How to make aggressive tax avoidance illegal? Great question, that opens up a whole can of worms.

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324739852882116609?s=20

First up, much tax avoidance *is* unlawful. Part of the problem here is that we've all heard the tax professionals and companies tell us for so long that the difference between avoidance and evasion is that (only) evasion is illegal.

In fact, much much corporate tax avoidance is subsequently ruled unlawful. Here's my colleague @nickshaxson making the case over at @FTAlphaville ftalphaville.ft.com/2019/05/16/155…

And even where it's never *ruled* as unlawful... lots of it is. If you require the administrative capacity and justice system to obtain that finding each time, you make it diminishingly likely that corporate tax abuse in countries with lower capacity will ever be deemed unlawful

So what can be done? One approach is to establish general anti-avoidance rules or principles (GAAR or GAAP, honest). Can help...

Another is to increase transparency of corporate tax data. In 2003, @RichardJMurphy worked with @TaxJusticeNet on the first ever draft accounting standard for country by country reporting, to require companies to report their profits, tax and real economic activity in each place

The introduction of even a very weak standard for public country by country reporting by EU banks led to a 10% increase in tax paid - many billions, just for turning on the light.

The OECD introduced a standard in 2015, based on our original proposals (but lobbied to be weaker), and tax authorities now have this data. But we the public need it to, because accountability - for both multinationals and tax authorities - is key to improving behaviour

But even the limited aggregate data that has now been published shows us new worlds of profit shifting - more than a trillion US dollars a year... taxjustice.net/2020/07/08/wat…

And then finally, to change the basis of the international tax rules. The current rules rest on the arm's length principle, which says that profit will end up in the right place (for tax) as long as entities within a multinational group transact with each other at market prices.

The arm's length principle is wrong and unworkable in oh so many ways. A big one: the rationale for multinationals to exist is that they can make *more* profit than a set of arm's length entities operating independently, and therefore outcompete them...

So applying arm's length prices logically *cannot* allocate the extra profit that multinationals can generate; and in principle wouldn't put the rest in the right place either. If it did, the multinationals wouldn't exist because arm's length entities would be more/as efficient.

[An aside: did the League of Nations, which chose arm's length over unitary tax alternatives, recognise this and decide it was ok because the supernormal profit would end up with the parent company, i.e. in the imperial capitals of the countries represented? Discuss...]

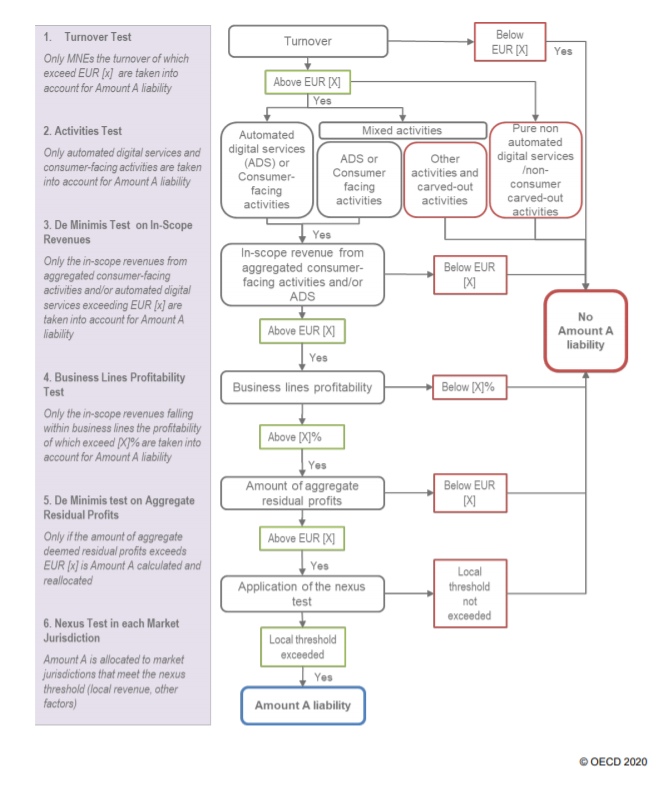

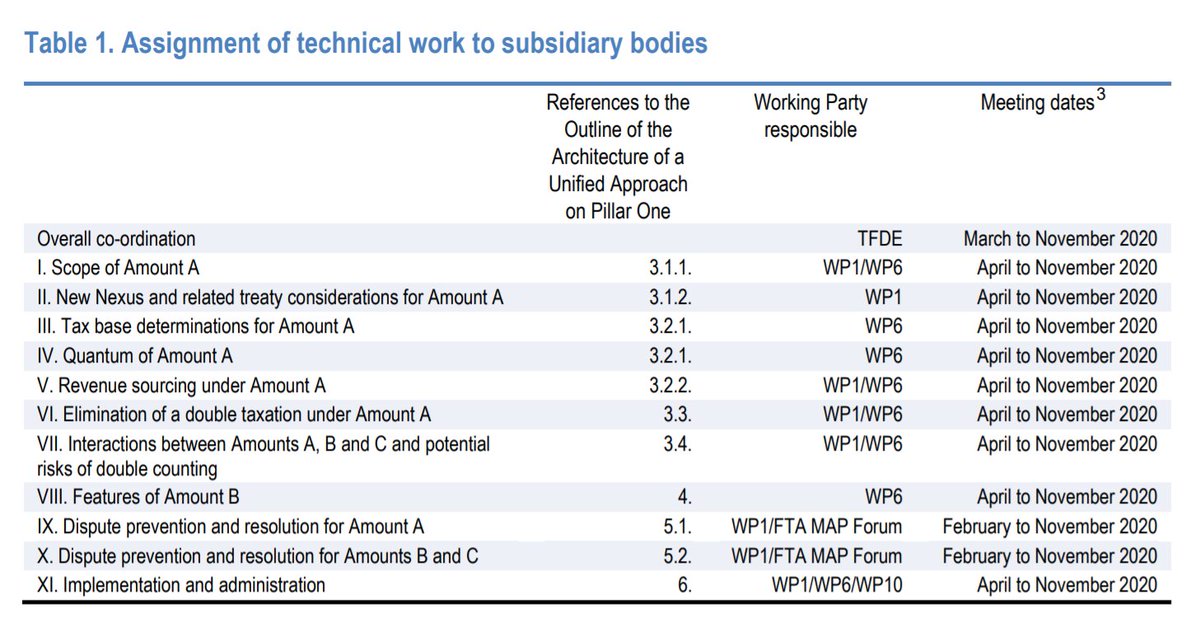

What is now being discussed, finally, in the international reform process, is moving *beyond* the arm's length principle, and considering at least some elements of unitary taxation and formulary apportionment - allocating the global profits to the countries of real activity.

This is ultimately the answer, cutting through the avoidance activity by tying profits to the underlying activity. There will still be games, but they'll be marginal rather than a central feature of the global economy as at present.

4. How to address IFFs in national accounts - taking a pause and coming back to this, and the next questions in a while.

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324739961933963265?s=20

We're back! This is a great question, raising points technical and conceptual.

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324739961933963265?s=20

Since IFFs are by definition hidden, what happens if we make them transparent? start capturing them rigorously in national accounts data?

We have some evidence on this. As mentioned above, for example, when European banks began to report some limited country by country reporting data to the public, their tax payments rose by about 10% - transparency really does curb illicit flows papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Equally, when the US tax authority receives information about taxable income automatically from a third party, the compliance of taxpayers is roughly 7 [SEVEN] times higher - transparency is a powerful disincentive to abuse.

But... national accounts data wouldn't immediately take us to the individual- or company-level transparency that would reveal the specific transactions in IFFs. From our discussions with @UNCTAD @UNODC, the possibilities are for aggregate data that would do two things...

First, national accounts data could highlight specific anomalies related to IFFs. Commodity trade data currently allows us to identify trade price anomalies, showing the scale of e.g. IFFs to Switzerland; but only occasionally revealing questionable individual behaviour

Here's a great example of (aggregate) commodity trade data aligning with individual commercial practices, just published on Indonesia's paper pulp production (the 'Macao Money Machine'): environmentalpaper.org/2020/11/new-ev…

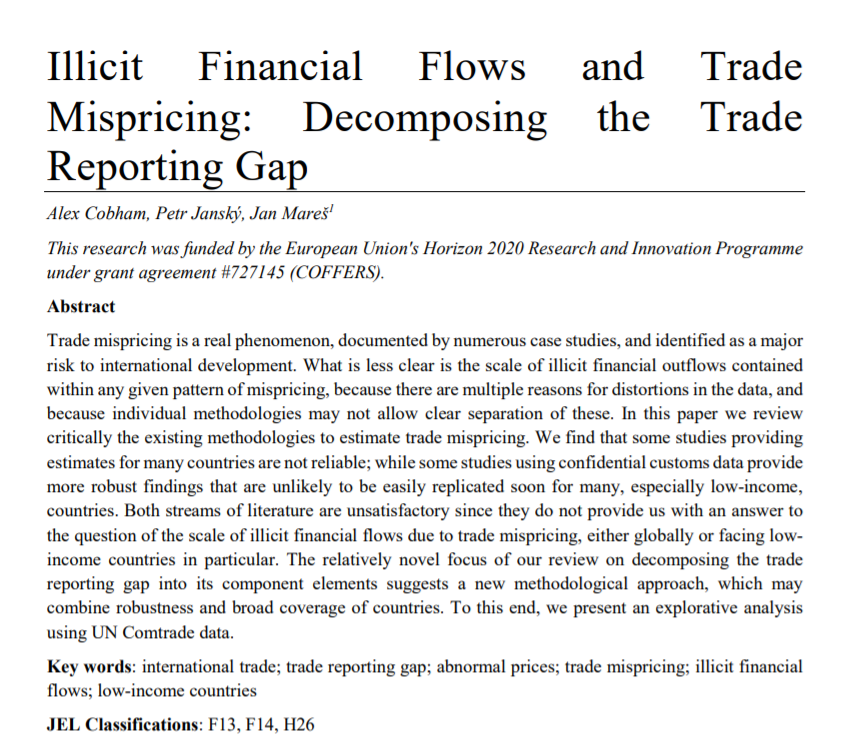

But national accounts improvements would generally support more aggregate anomaly analysis, as in e.g. this commodity work with @petr_jansky and @JanMares from @COFFERSEU coffers.eu/wp-content/upl…

So getting this right could allow independent researchers to identify the major potential IFFs by channel - giving government agencies the starting point to do more detailed audits with their privately held data. This is likely to reduce the underlying IFF, but not eliminate them

But then - how far would companies go to distort the data, knowing it could be used this way? This is always a risk, with any data; and the more likely it is to be used for individual audit, the greater the risk; but also the greater in general the penalties for misfiling...

For example, the US survey of multinationals has historically generated decent data, in part perhaps because companies know it does not reveal their own behaviour - whereas heavy lobbying has focused on resisting individual *public* country by country reporting that would

All of which is to say that there may be a tradeoff: adding national accounts data that gives a clearer picture of the overall issues, without identifying individual IFF actors, may end up being better data than if we try to construct measures to support tax/criminal enforcement

So, I'm biased but...

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324740074186133509?s=20

For an overview of the range and robustness of all the leading IFF estimates, please see our (!) #openaccess @OUPEconomics book with @petr_jansky global.oup.com/academic/produ…

For granular measures of the comparative IFF risks in the main trade and financial stock/flow channels, the @TaxJusticeNet data portal expands the pioneering work with @alicelepissier for the @ECA_OFFICIAL/@_AfricanUnion Mbeki panel: iff.taxjustice.net/#/

And lastly🚨if you'd like global and country-level measures of the estimated revenue losses due to corporate tax abuse and individual offshore evasion, along with detail of the revenue losses caused by each jurisdiction to others - the State of Tax Justice 2020 is just days away!

This is a good question, but a difficult one to answer. Have IFFs been increasing over time?

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324740355867246592?s=20

The data in the graph require a bit of caution - first, they predate the financial crisis, after which our issues began to gain much more political traction, which may have changed trajectories.

Second, the estimates shown relate mainly to commodity trade. This is only one channel, and lacks consensus on a good, 'conservative' approach to estimates, so there remain questions here (see our chapter on trade-based IFF to get a sense of where things stand).

But it's also entirely possible that IFF have been increasing. The most robust estimates are those for corporate profit shifting, which exploded 1990s-2010s, and despite a serious lag on data availability, there's nothing yet to suggest that the problem has begun to diminish.

We may be getting somewhat better at tracking IFF patterns; it's not clear that we are yet any better at fighting it. Plus the global geopolitical context in recent years: the mood music from the world's major economy has been more supportive of impunity than accountability.

And last, from @NimiHoffmann's outstanding students, the (literally) trillion dollar question: how can governments now reduce IFF?

https://twitter.com/NimiHoffmann/status/1324740458615132160?s=20

If it was easy, someone would have shut down IFF already; but, ultimately, the problem is more political than technical. We don't stop IFF not because we can't, but because we don't want to.

In reality, one of these overlaps is *much* bigger than the other...

In reality, one of these overlaps is *much* bigger than the other...

We @TaxJusticeNet and many allies at @GA4TJ and @FinTrCo and elsewhere, have too often seen the political will to combat IFF dissipate at just the moment when you start to see who the main actors may be.

But - there is a lot that governments can do, both domestically and multilaterally.

Domestically, the tools are there to identify biggest risks and to get much better at allocating scarce resources to curb the biggest IFF. (We work with govts in various regions, doors are open)

Domestically, the tools are there to identify biggest risks and to get much better at allocating scarce resources to curb the biggest IFF. (We work with govts in various regions, doors are open)

Country by country reporting, even with the weak OECD standard, provides a great way to target profit shifting. The Common Reporting Standard is a great way in to compare offshore financial accounts with what individuals report to tax authorities, then target audits.

The problem, all too often, is that lower-income countries are shut out of OECD information - so that the transparency tools we designed to reduce the global inequalities in taxing rights may actually exacerbate them, so unfairly are they now designed.

Individual governments can do *a lot* with the data they have, and by requiring more - e.g. direct local filing of country by country data, and unilateral minimum tax measures to curb profit shifting (a proposal on which coming shortly with @SolPicciotto)

But multilateral measures are needed at the UN rather than OECD level - and the final report of the @FACTIpanel will be important in setting out what changes could look like. Their interim report identifies the key gaps in the global IFF architecture taxjustice.net/2020/09/24/our…

The @FACTIpanel is now in regional consultations (Europe is in a few hours), and will deliver its final report in February. The hope is that it will include the scope for comprehensive measures including access to data for all countries, and the creation of a global policy forum

The right transparency measures have dual power: they allow governments to track and curb IFF directly, and they also deliver the data for public accountability of governments themselves. Locking in the second of these makes the first much more likely over time.

And to return, finally to the starting point of this set of threads: locking in powerful transparency measures, in SDG 16.4 indicators and national accounts data, will set the world on a much better path for accountability and lower IFF, rather than continuing impunity.

Thanks for sticking with this very long thread, and many thanks to @NimiHoffmann and her students for such thought-provoking questions!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh