In the new volume by Segovia, there's an article that makes me feel like we have stepped into a time machine, all progress of the past decades is ignored. Emilio Ferrín argues for a Wansbrough-style late (post 800 CE) compilation of the Quran.

Here's why this doesn't work. 🧵

Here's why this doesn't work. 🧵

https://twitter.com/DanielABeck9/status/1335622040250765313

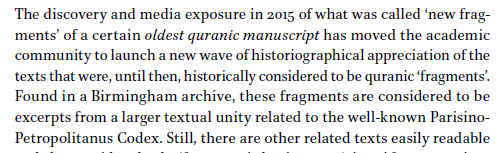

Ferrín pays lip service to the existence of Quranic manuscript fragments, but takes issue with the term "fragments" as it suggests that these "fragments" are part of a "whole". But he considers the texts to be compiled together only later.

It's rather clear that he has never actually looked at any of these manuscripts, otherwise he would not suggest something so absurd. And indeed, his discussion on early manuscripts makes it quite clear he is utterly clueless about them.

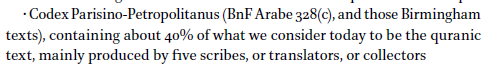

First he is under the impression that the Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus consists of BnF Arabe 328(c) and the Birmingham fragments.

This is wrong, and that should even be obvious for the name. It's not called Codex Parisino-Birminghamensis.

This is wrong, and that should even be obvious for the name. It's not called Codex Parisino-Birminghamensis.

Indeed Arabe 328(c) and the Birmingham fragment belongs to one and the same manuscript. But it is NOT part of the CPP. This is a myth that has made it into multiple publications. But it is still wrong. It would have helped if he had maybe read & cited the publication on the CPP.

The CPP's main portions come from Paris and St. Petersburg (hence: PARISino-PETROPOLItanus)

The CPP consists of BnF Arabe 328(a) and 328(b) (not (c)!)

And St. Petersburg National Library Marcel 18.

Then two more folios: Vatican Library Ar. 1605/1 and Khalili Islamic Art KFQ 60.

The CPP consists of BnF Arabe 328(a) and 328(b) (not (c)!)

And St. Petersburg National Library Marcel 18.

Then two more folios: Vatican Library Ar. 1605/1 and Khalili Islamic Art KFQ 60.

The list of 'manuscripts' that he considers part of Early manuscripts is laughable. Why isn't anyone who has worked on the Sanaa manuscripts cited? Why pretend like it is only Inārah that has looked at them. Insulting to Sadeghi & Goudarzi, Hilali and Cellard.

Tübingen fragmenta ??? There's one manuscript there as far as I know (Ma VI 165). 77 folios of continuous Quran text.

Topkapı and Samarkand are important but also MUCH later than much more important manuscripts from earlier periods.

Many even carbon-dated manuscripts are older.

Topkapı and Samarkand are important but also MUCH later than much more important manuscripts from earlier periods.

Many even carbon-dated manuscripts are older.

Bizarrely absent are British Library Or. 2165, Arabe 331, Arab 330g/Marcel 16/CBL Is.1615 II, Sanaa DAM 01-29.1, Qāf 47, etc. all of which are earlier than Topkapı/Samarkand (and importantly earlier than 800) and cover a large portion of the now canonical Quranic text.

These texts are all EXTREMELY similar when they have overlapping portions. To suggest that they are not all copied from a common source is so utterly disconnected from reality. The author would have been helped by reading my paper: doi.org/10.1017/S00419…

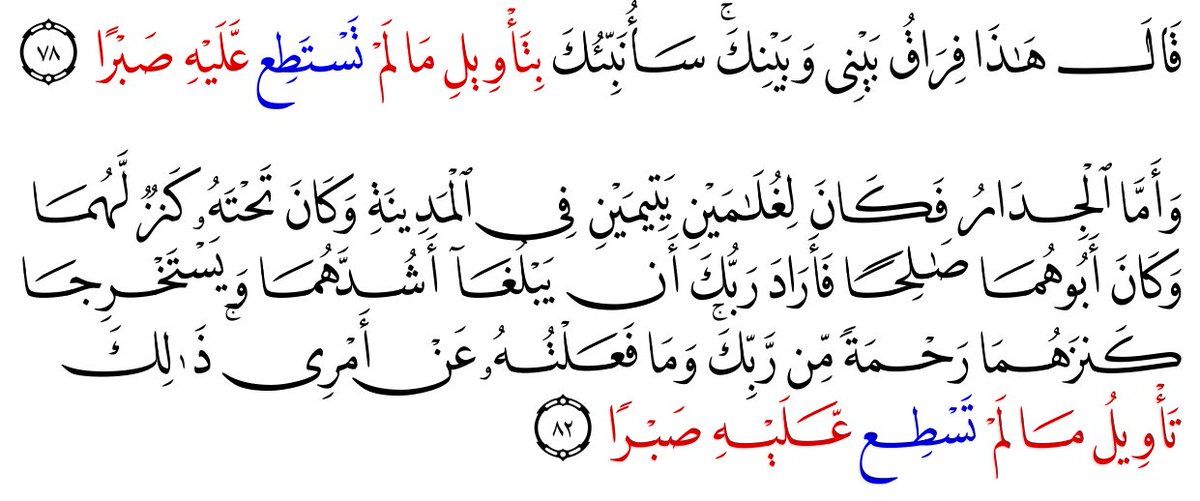

But let us assume that when they paper was written predated June 2019 and he was unaware of this evidence: why does it still not make sense to think of the Quran as "pieces of Quran" that were only compiled together into a single text post-800, rather than "fragments of a whole"?

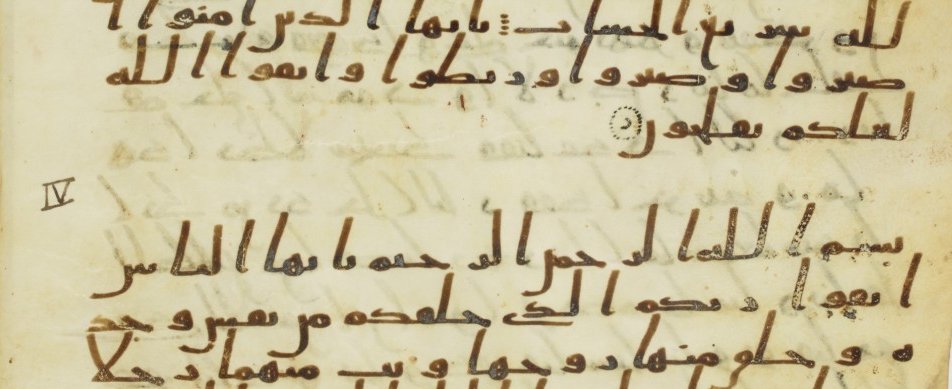

Early Quranic manuscripts are continuous in surahs. You don't have a fragment of folios that contains a single Surah, and another that contains another one. Something the author seems unaware of, because he had no interest in letting material evidence get in the way of his theory

Even taking JUST the CPP, we have the following transitions: 2>3>4>5; 6>7>8>9>10>11; 12>13>14>15; 23>24>25>26>27>28; 30>31; 38>39; 41>42>43>44>45>46; 56>57; 60>61>62>63; 65>66>67; 69>70>71>72

That's 32 transitions, all of these transitions are canonical.

That's 32 transitions, all of these transitions are canonical.

Never do we find a fragment that starts at a Sūrah, clearly suggesting that the "piece of Quran" started there. You always see the trace of the previous surah and it is ALWAYS canonical. Simple extrapolation should teach you that the order was fixed in the time of the CPP.

So even if the text DIDN'T have a single written archetype as its origin (which it does) it is utterly clear that the contents of the Quran from beginning to end were agreed upon and had an agreed upon order, and the transmission of the Quran was not in "pieces" but a full text.

If you perhaps feel that 32 transitions of one manuscript are not enough to make this extrapolation, please go check out the transition of the other manuscripts that Ferrín conveniently ignored. Or try the ACTUAL "Codex Parisino-Birminghamensis": 10>11, 18>19>20>21>22>23

The vast majority of the canonical transitions are attested multiple times in pre-800 manuscripts. Now if you would want to be revisionist and argue some of the missing ones point to those bits not being part of the original Quran, that's a different story.

I'm sure I sound very frustrated. But the fact that such claims can be publishing in 2020 -- with decades of massive advancements since Wansbrough -- full of claims that can be debunked by any person with a brain, is truly infuriating.

How on earth are we to advance our understanding of the history of the Quran, if those with revisionist views (which are always important) are essentially writing their own alternate universe fan fiction, rather than be informed by the actual undeniable material evidence?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh