1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand Warren Buffett's famous quote: it's better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than a fair business at a wonderful price.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you understand Warren Buffett's famous quote: it's better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than a fair business at a wonderful price.

2/

This quote has 2 parts:

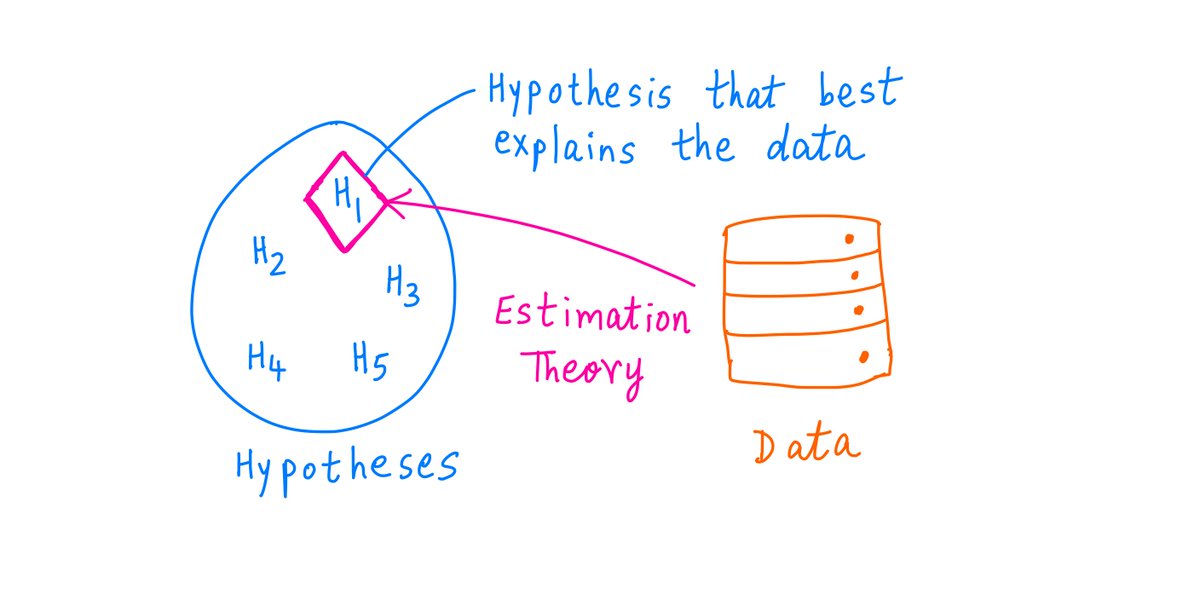

Part 1. Business Quality. To understand this, we need a way to distinguish *wonderful* businesses from just fair/mediocre ones.

Part 2. Price. We should know when we're getting a business for a wonderful price, and when we're paying too much for it.

This quote has 2 parts:

Part 1. Business Quality. To understand this, we need a way to distinguish *wonderful* businesses from just fair/mediocre ones.

Part 2. Price. We should know when we're getting a business for a wonderful price, and when we're paying too much for it.

3/

And the quote itself says that Part 1 (Business Quality) is way more important than Part 2 (Price).

So let's dive into Part 1. What makes a business *wonderful*?

And the quote itself says that Part 1 (Business Quality) is way more important than Part 2 (Price).

So let's dive into Part 1. What makes a business *wonderful*?

4/

When we hear the phrase "wonderful business", we tend to think of companies that give us wonderful products and services. Eg, Apple's iPhone, Google's Maps, etc.

But that's not what Buffett means when he says "wonderful business".

When we hear the phrase "wonderful business", we tend to think of companies that give us wonderful products and services. Eg, Apple's iPhone, Google's Maps, etc.

But that's not what Buffett means when he says "wonderful business".

5/

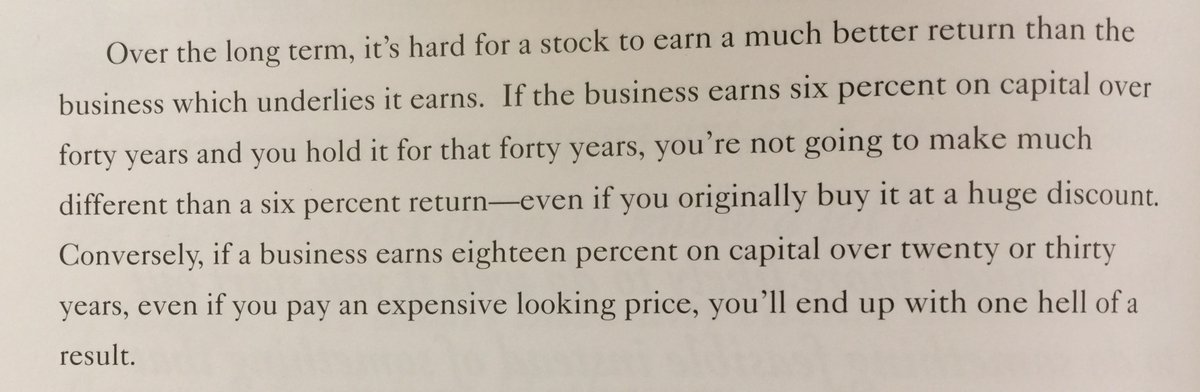

Buffett thinks about businesses from the standpoint of an *owner*.

To Buffett, a wonderful business is simply one that's able to deliver great returns for its *owners* -- ie, compound their money at a fast rate.

Let's flesh this out in a bit more detail.

Buffett thinks about businesses from the standpoint of an *owner*.

To Buffett, a wonderful business is simply one that's able to deliver great returns for its *owners* -- ie, compound their money at a fast rate.

Let's flesh this out in a bit more detail.

6/

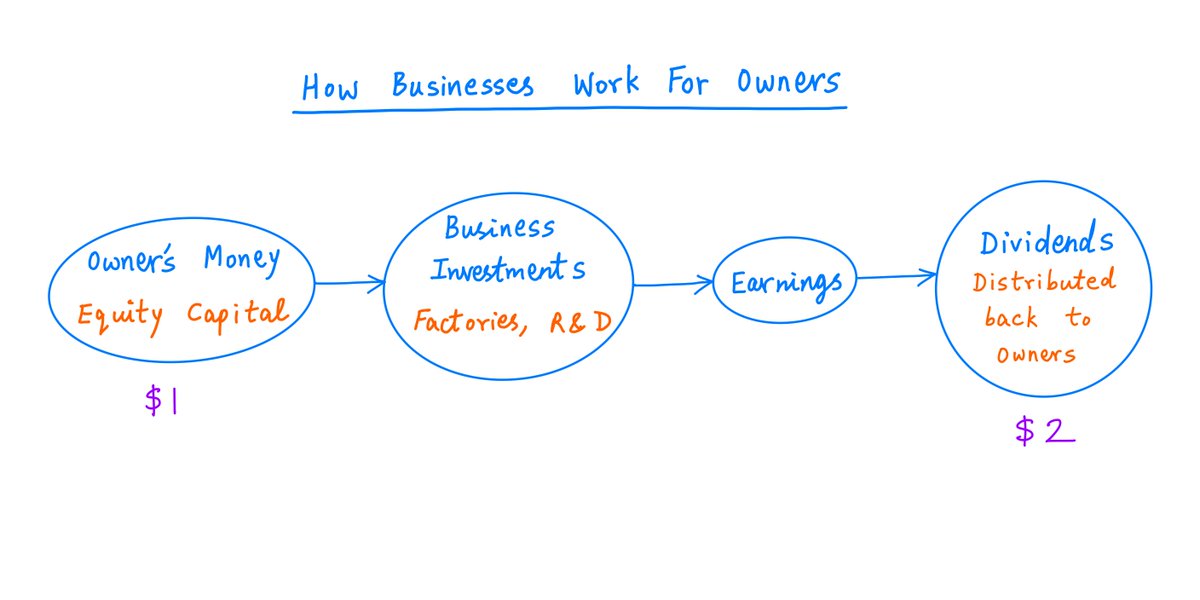

At its core, a business works like this.

The owners of the business put money into it. This money is called *equity capital*.

This equity capital is then *invested*. It is used to build factories, research and develop new products, etc.

At its core, a business works like this.

The owners of the business put money into it. This money is called *equity capital*.

This equity capital is then *invested*. It is used to build factories, research and develop new products, etc.

7/

Over time, these investments produce *earnings* (profits) for the business.

And these earnings are then distributed back to the owners of the business -- as *dividends*.

A quick picture:

Over time, these investments produce *earnings* (profits) for the business.

And these earnings are then distributed back to the owners of the business -- as *dividends*.

A quick picture:

8/

Of course, the owners only stand to gain when they receive more in dividends from the business than the equity capital they put into it.

The basic idea is to use the business as a vehicle to turn $1 of equity capital into $2 of dividends.

Of course, the owners only stand to gain when they receive more in dividends from the business than the equity capital they put into it.

The basic idea is to use the business as a vehicle to turn $1 of equity capital into $2 of dividends.

9/

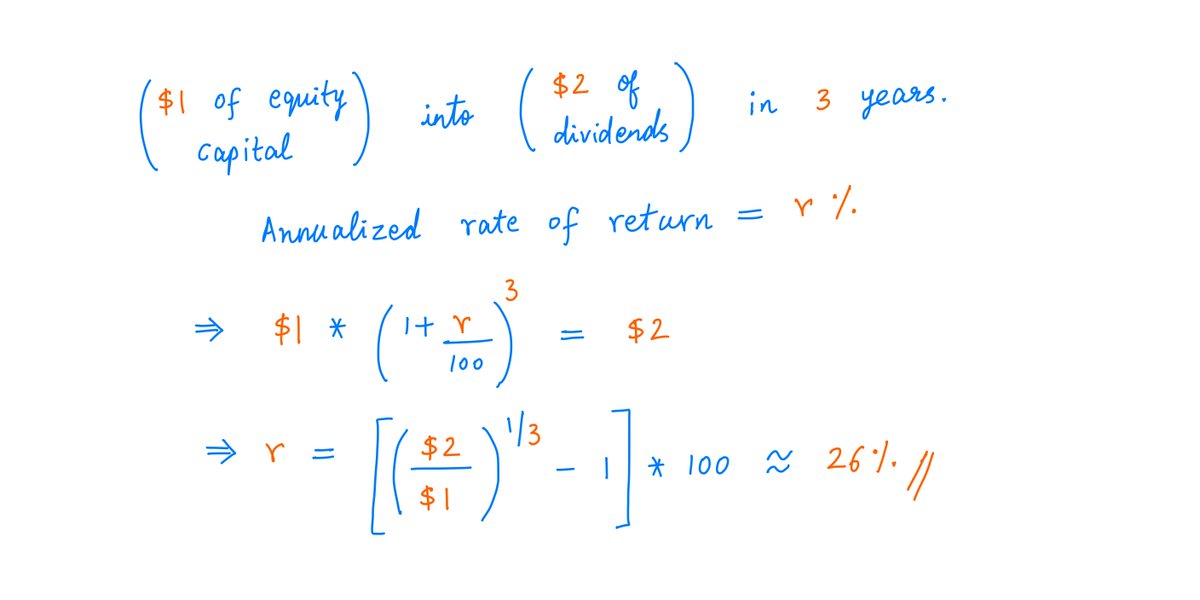

The timing also matters a great deal.

For example, if the business is able to turn $1 of equity capital into $2 of dividends in just 3 years, that's a very good return (about 26% annualized) for the owners.

The timing also matters a great deal.

For example, if the business is able to turn $1 of equity capital into $2 of dividends in just 3 years, that's a very good return (about 26% annualized) for the owners.

10/

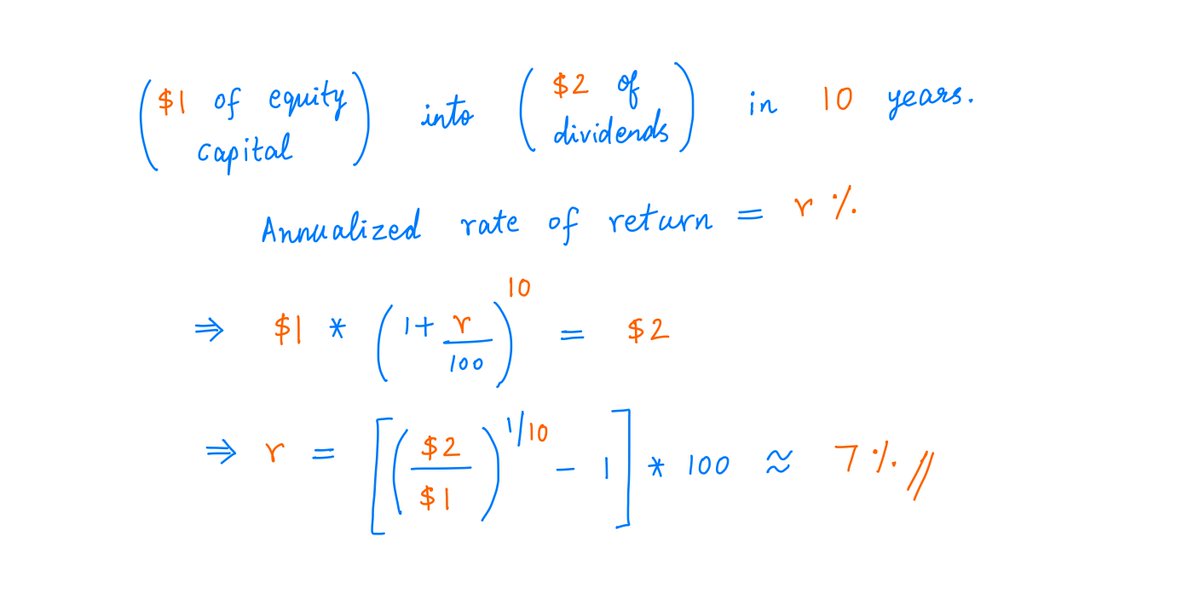

But if the business takes *10* years to turn the same $1 of equity capital into the same $2 of dividends, that's a much worse result for the owners -- an annualized return of only ~7%.

But if the business takes *10* years to turn the same $1 of equity capital into the same $2 of dividends, that's a much worse result for the owners -- an annualized return of only ~7%.

11/

This gives us an important clue to distinguish wonderful businesses from fair/mediocre ones:

Wonderful businesses earn high returns on their owners' equity capital.

This gives us an important clue to distinguish wonderful businesses from fair/mediocre ones:

Wonderful businesses earn high returns on their owners' equity capital.

12/

But a "high return on equity capital" is not the *only* factor.

Businesses are perpetual entities. They don't just convert $1 of their owners' money into $2 and then close shop.

They try to repeat this trick many times -- over and over again.

But a "high return on equity capital" is not the *only* factor.

Businesses are perpetual entities. They don't just convert $1 of their owners' money into $2 and then close shop.

They try to repeat this trick many times -- over and over again.

13/

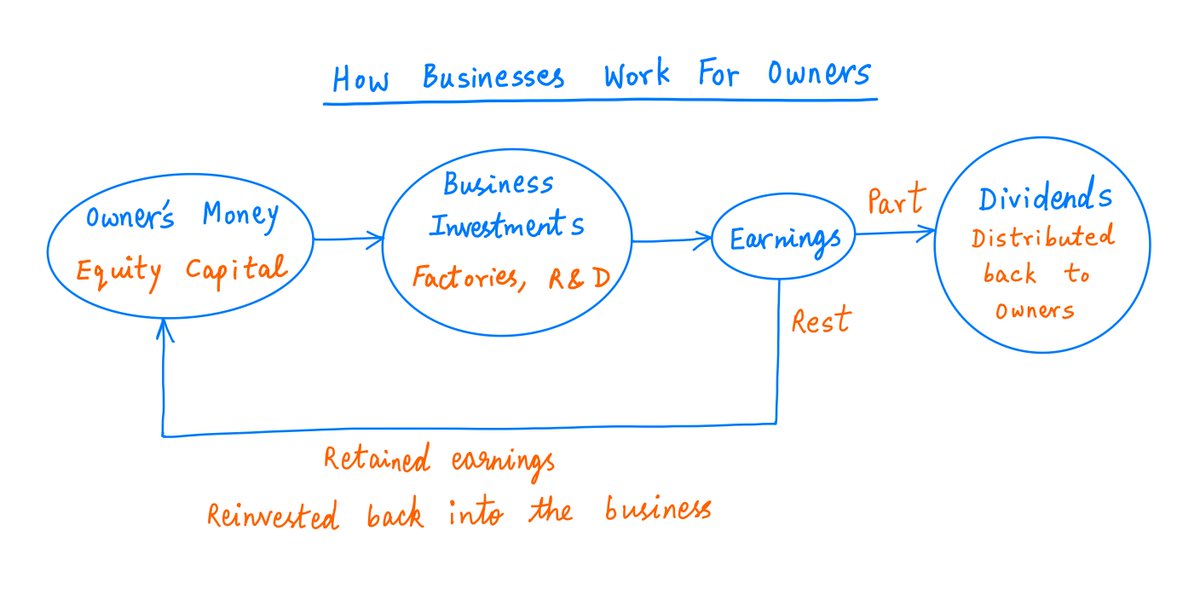

The "mechanism" they use to do this is called *retained earnings*.

Instead of distributing the entire $2 of earnings back to owners as dividends, a business typically distributes only *part* of it -- say $0.50.

The "mechanism" they use to do this is called *retained earnings*.

Instead of distributing the entire $2 of earnings back to owners as dividends, a business typically distributes only *part* of it -- say $0.50.

14/

What about the remaining $1.50?

That's called "retained earnings". The business *retains* it instead of distributing it to owners.

This retained earnings is *reinvested* back into the business -- to build new factories, develop new products, etc.

What about the remaining $1.50?

That's called "retained earnings". The business *retains* it instead of distributing it to owners.

This retained earnings is *reinvested* back into the business -- to build new factories, develop new products, etc.

15/

And this produces even more earnings.

Which leads to even more in dividends for owners, and even more in retained earnings and reinvestments.

Which increases earnings even further.

And so on.

And this produces even more earnings.

Which leads to even more in dividends for owners, and even more in retained earnings and reinvestments.

Which increases earnings even further.

And so on.

16/

This is the second factor separating wonderful businesses from fair/mediocre ones.

In addition to high returns on equity capital, *wonderful* businesses have long *reinvestment runways*. They can reinvest a big part of their earnings back into the business at high returns.

This is the second factor separating wonderful businesses from fair/mediocre ones.

In addition to high returns on equity capital, *wonderful* businesses have long *reinvestment runways*. They can reinvest a big part of their earnings back into the business at high returns.

17/

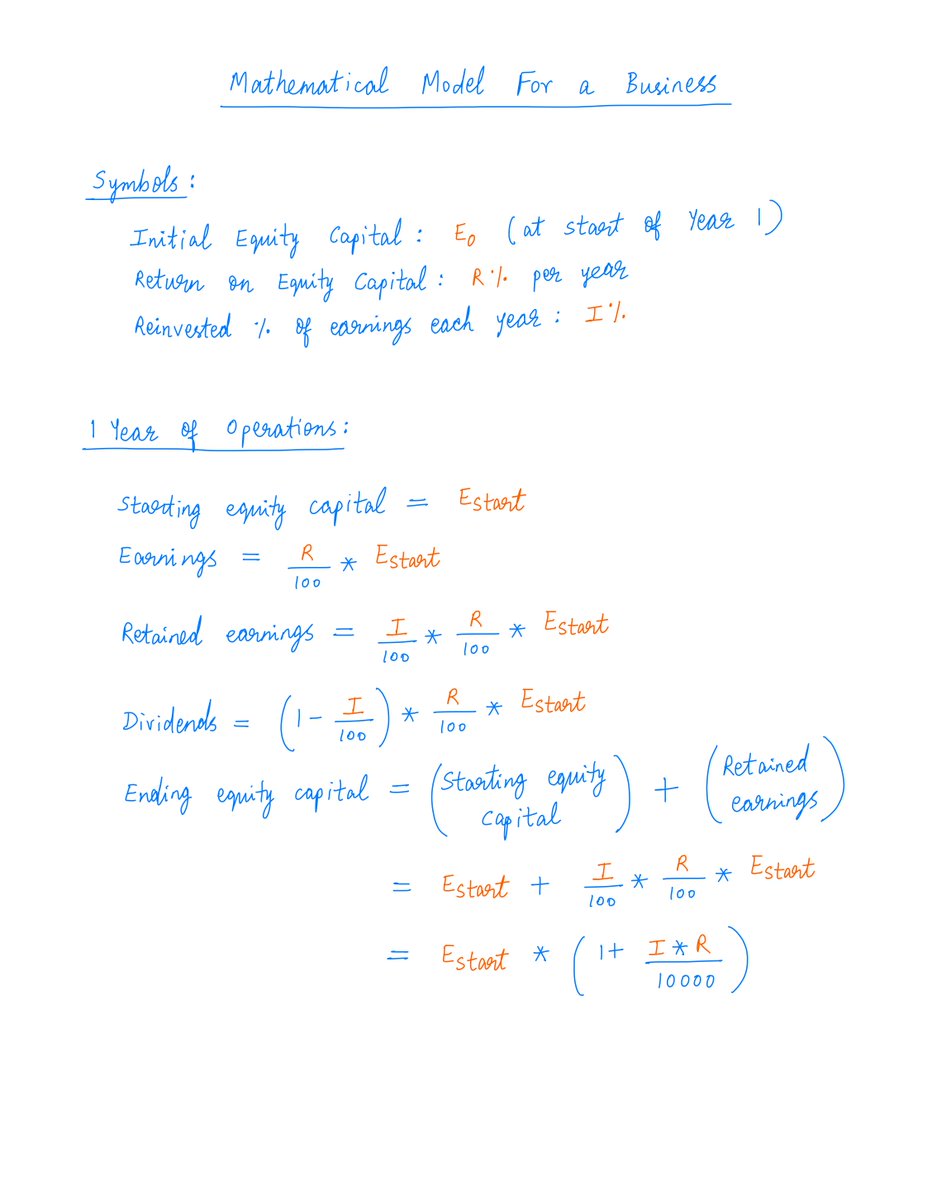

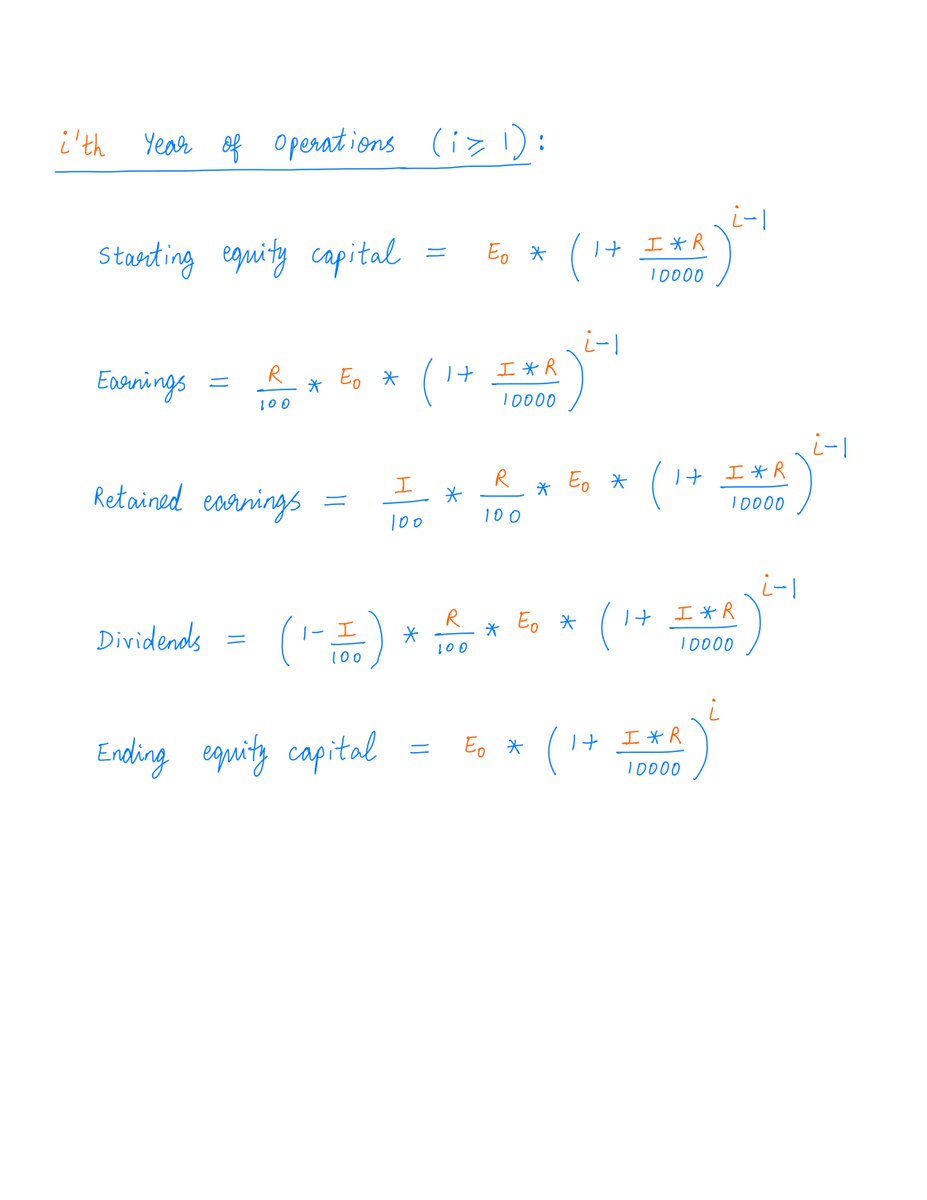

Let's build a mathematical model for this.

We'll assume that our business earns R% per year on equity capital.

It retains I% of these earnings -- and reinvests them at the same R% return. The remaining (100 - I)% of earnings are distributed to owners as dividends.

Let's build a mathematical model for this.

We'll assume that our business earns R% per year on equity capital.

It retains I% of these earnings -- and reinvests them at the same R% return. The remaining (100 - I)% of earnings are distributed to owners as dividends.

18/

*Wonderful* businesses in our model will have bigger Rs and Is.

Fair/mediocre businesses will have smaller Rs and Is.

So that's our analysis of the first part of Buffett's quote -- the "Business Quality" part.

*Wonderful* businesses in our model will have bigger Rs and Is.

Fair/mediocre businesses will have smaller Rs and Is.

So that's our analysis of the first part of Buffett's quote -- the "Business Quality" part.

19/

Let's now look at the second part -- Price.

We know that the Price/Earnings (P/E) multiple is a simple way to gauge how expensive a business is.

So let's just use that in our analysis.

Let's now look at the second part -- Price.

We know that the Price/Earnings (P/E) multiple is a simple way to gauge how expensive a business is.

So let's just use that in our analysis.

20/

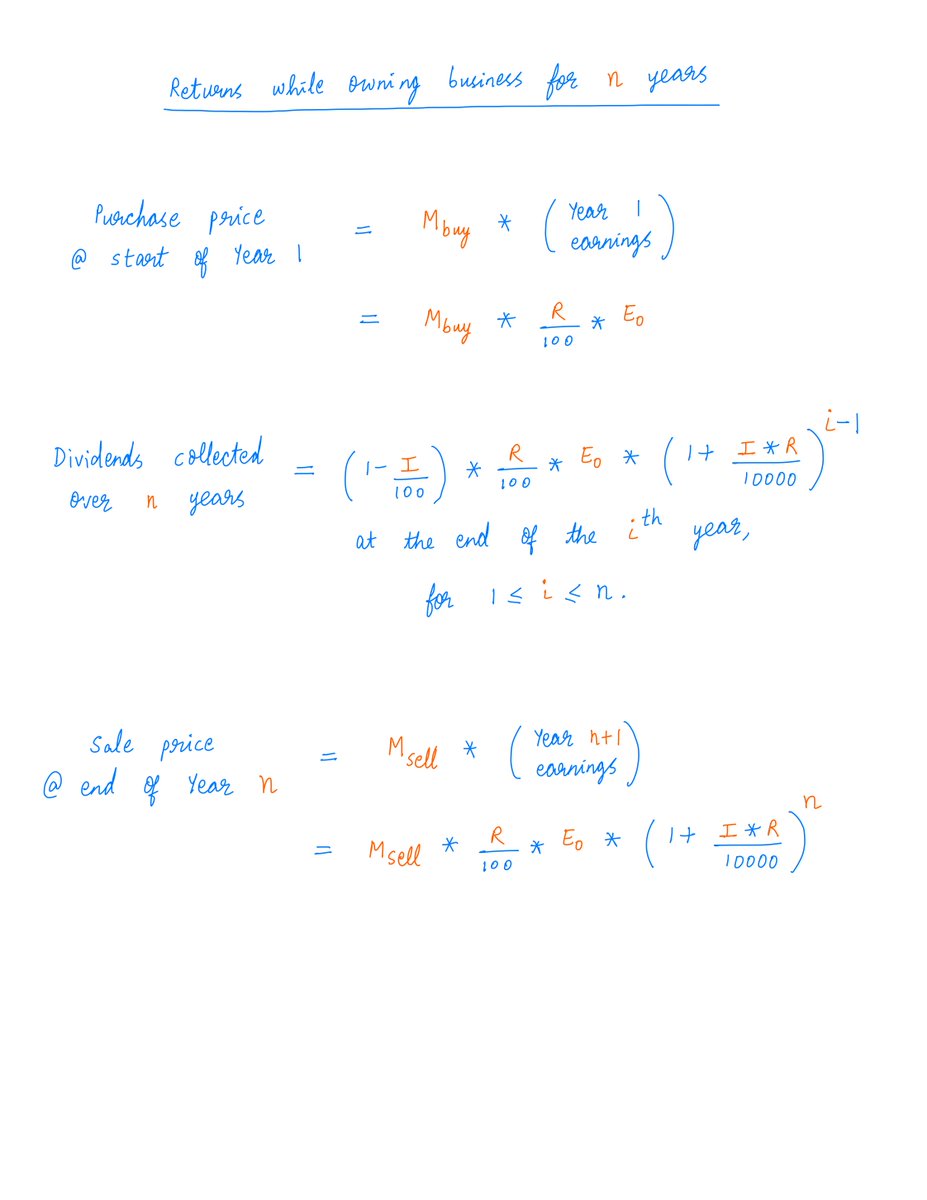

Let's say that, at the start of Year 1, we buy a business at a P/E multiple of M_buy.

And n years later -- at the end of Year n -- we sell the business at a P/E multiple of M_sell.

The question is: what will our annualized return be over these n years?

Let's say that, at the start of Year 1, we buy a business at a P/E multiple of M_buy.

And n years later -- at the end of Year n -- we sell the business at a P/E multiple of M_sell.

The question is: what will our annualized return be over these n years?

21/

This is just an IRR calculation.

There's only 1 "outflow": our business purchase.

There are n+1 "inflows": our n dividends and our final business sale.

Our annualized return is the discount rate at which our inflows cancel our outflow.

For more:

This is just an IRR calculation.

There's only 1 "outflow": our business purchase.

There are n+1 "inflows": our n dividends and our final business sale.

Our annualized return is the discount rate at which our inflows cancel our outflow.

For more:

https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1284536987861446657

22/

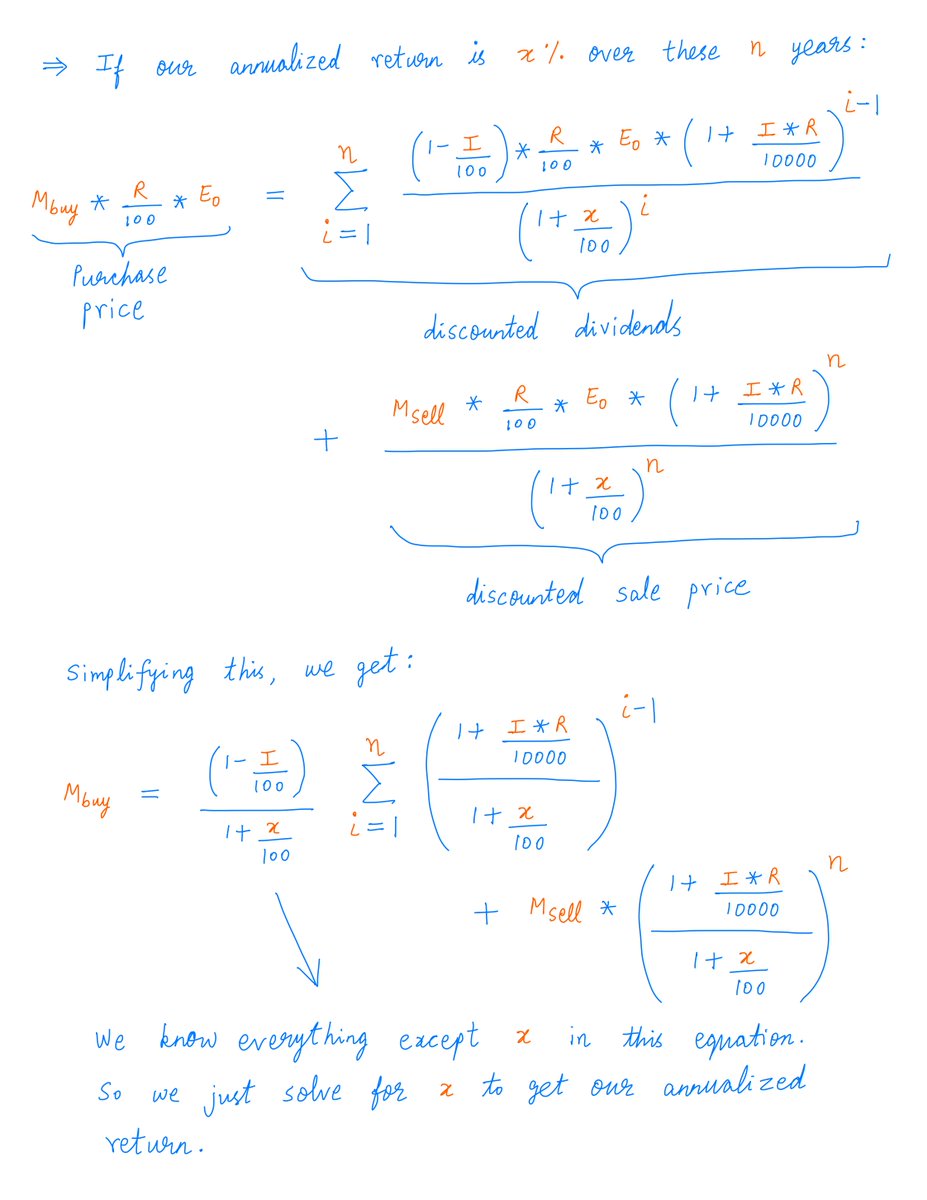

For the mathematically inclined, here's the algebra for calculating our annualized return.

(Don't worry if you don't fully understand this math!)

For the mathematically inclined, here's the algebra for calculating our annualized return.

(Don't worry if you don't fully understand this math!)

23/

When we do the calculations, a very interesting pattern emerges:

The longer we hold the business, the more our returns are determined by Business Quality (returns on equity capital and reinvestment runways) rather than Price (the difference between M_buy and M_sell).

When we do the calculations, a very interesting pattern emerges:

The longer we hold the business, the more our returns are determined by Business Quality (returns on equity capital and reinvestment runways) rather than Price (the difference between M_buy and M_sell).

24/

For example, let's say we have 2 businesses: W and F.

W is a Wonderful business. It returns 20% per year on equity capital. Moreover, 80% of earnings each year can be retained and reinvested into the business -- at this same 20% return.

For example, let's say we have 2 businesses: W and F.

W is a Wonderful business. It returns 20% per year on equity capital. Moreover, 80% of earnings each year can be retained and reinvested into the business -- at this same 20% return.

25/

F, on the other hand, is only a Fair business.

It earns only 6% per year on equity capital. And like W, it also retains 80% of earnings each year -- and earns 6% on these as well.

F, on the other hand, is only a Fair business.

It earns only 6% per year on equity capital. And like W, it also retains 80% of earnings each year -- and earns 6% on these as well.

26/

Let's say we buy both businesses at a P/E multiple of 20.

We hold both for several years, and eventually sell them.

Our annualized returns in each case will depend on two variables: how long we hold these businesses, and at what multiple we sell them.

Let's say we buy both businesses at a P/E multiple of 20.

We hold both for several years, and eventually sell them.

Our annualized returns in each case will depend on two variables: how long we hold these businesses, and at what multiple we sell them.

27/

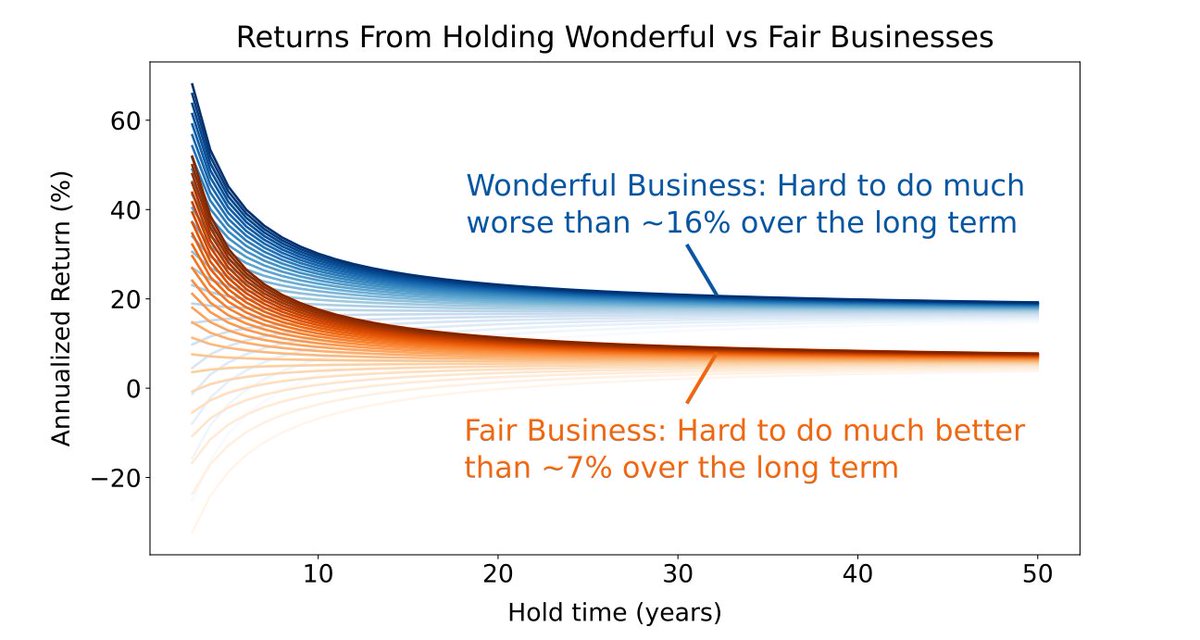

Here's a plot showing the returns we get for various holding periods and sale multiples.

Each blue curve is for a different sale multiple (ranging from 5 to 60) for the Wonderful business W.

And the orange curves are for the same sale multiples -- for the Fair business F.

Here's a plot showing the returns we get for various holding periods and sale multiples.

Each blue curve is for a different sale multiple (ranging from 5 to 60) for the Wonderful business W.

And the orange curves are for the same sale multiples -- for the Fair business F.

28/

As you can see, if we hold the business long enough, it's hard to do much worse than ~16% annualized with the Wonderful business W, or much better than ~7% with the Fair business F -- *regardless* of our purchase and sale prices.

This is what Buffett meant by his quote.

As you can see, if we hold the business long enough, it's hard to do much worse than ~16% annualized with the Wonderful business W, or much better than ~7% with the Fair business F -- *regardless* of our purchase and sale prices.

This is what Buffett meant by his quote.

29/

Of course, we've made a few assumptions with our model.

We've only considered returns on equity capital (no debt).

We haven't considered buybacks (only dividends).

Our return calculations are all pre-tax.

But the broad point remains valid: Business Quality trumps Price.

Of course, we've made a few assumptions with our model.

We've only considered returns on equity capital (no debt).

We haven't considered buybacks (only dividends).

Our return calculations are all pre-tax.

But the broad point remains valid: Business Quality trumps Price.

31/

I also recommend watching this excellent video where Terry Smith describes his 3-step investment process:

Step 1: Find wonderful businesses,

Step 2: Buy them at reasonable prices, and

Step 3: Do nothing.

(h/t @timelessfinance for sharing it with me)

I also recommend watching this excellent video where Terry Smith describes his 3-step investment process:

Step 1: Find wonderful businesses,

Step 2: Buy them at reasonable prices, and

Step 3: Do nothing.

(h/t @timelessfinance for sharing it with me)

32/

Thank you very much for patiently reading to the end of another long thread.

Take care. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

Thank you very much for patiently reading to the end of another long thread.

Take care. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh