Is it true that democracies don't go to war with each other?

Sort of. But I wouldn't base public policy on the finding.

Why? Let's turn to the data.

[THREAD]

Sort of. But I wouldn't base public policy on the finding.

Why? Let's turn to the data.

[THREAD]

https://twitter.com/McFaul/status/1337620255997247488

The idea of a "Democratic Peace" is a widely held view that's been around for a long time.

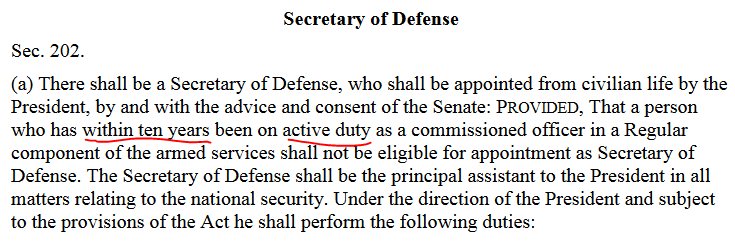

By 1988, there already existed enough studies on the topic for Jack Levy to famously label Democratic Peace "an empirical law"

By 1988, there already existed enough studies on the topic for Jack Levy to famously label Democratic Peace "an empirical law"

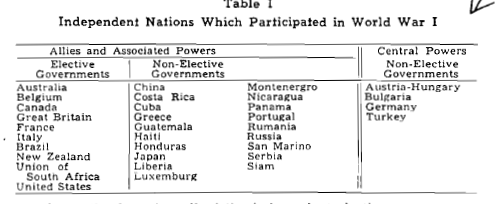

The earliest empirical work on the topic was the 1964 report by Dean Babst published in the "Wisconsin Sociologist"

Using the war participation data from Quincy Wright's "A Study of War", Babst produced the following two tables

The tables show that democracies were NOT on both sides (of course, Finland is awkward given that it fought WITH Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union).

Babst expanded his study beyond the World Wars in a 1972 paper in Industrial Research. He confirmed his finding.

Babst expanded his study beyond the World Wars in a 1972 paper in Industrial Research. He confirmed his finding.

In a 1976 paper published in the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations, J.D. Singer and Melvin Small sought to replicate and challenge Babst's findings

But they confirmed the finding that democracies (what they call "bourgeois democracies") do not appear to attack one another

The Journal of Conflict Resolution (finally, a journal I recognize) got into the act in 1983 with a paper by Rudy Rummel

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00…

Rummel looked at "Libertarian states", meaning states that emphasize individual freedom and hold competitive open elections, do not fight one another.

As shown below, there are simply no dots on the left-hand side.

As shown below, there are simply no dots on the left-hand side.

So these were the studies that led Levy to make his "empirical law" claim.

But the work didn't stop (perhaps BECAUSE Levy made that claim)

But the work didn't stop (perhaps BECAUSE Levy made that claim)

In particular, Zeev Maoz and Bruce Russett published two papers in the early 1990s that setup the study of democratic peace for a new generation of scholars.

The first, with a very descriptive title, was published in @II_journal in 1992

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

The first, with a very descriptive title, was published in @II_journal in 1992

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

The second, and more famous paper, was published in @apsrjournal in 1993

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

A key innovation of the papers was to expand the consideration of "conflict" to "militarized interstate disputes (MIDs)", not just wars.

MIDs include wars and "lower levels of conflict", like 👇

MIDs include wars and "lower levels of conflict", like 👇

https://twitter.com/ProfPaulPoast/status/1047456380834238465

In short, all wars are MIDs, but not all MIDs are wars.

This allowed Maoz and Russet to really find out how "pacific" democracies are to one another.

This allowed Maoz and Russet to really find out how "pacific" democracies are to one another.

Both papers find that "democracies engage in militarized disputes with each other less than would be expected by chance"

So conflict is less (see neg coefficient in the logit model from their 1993 paper), but not zero.

So conflict is less (see neg coefficient in the logit model from their 1993 paper), but not zero.

This negative coefficient essentially became the focus of a host of further studies: studies seeking to confirm that it was negative...or show that it was a spurious finding.

Russett himself published a 1997 paper with John Oneal seeking to show how democracy is one part of a "triad of peace" (along with IO membership and dyadic trade)

academic.oup.com/isq/article-ab…

academic.oup.com/isq/article-ab…

Using a "dyadic design" (state A, state B, year t) they find that the higher is the lower of the two "Democracy" scores in the dyad, the less likely is the dyad to enter a conflict (did you follow that?)

This particular paper set off a long series of papers trying to identify an omitted variable that would wipe-out the relationship, along with Oneal and Russett responding to those papers.

These omitted variables included...

These omitted variables included...

...Cold War interests...

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

...and, most recently, it might be the case that the "Democratic Peace" is really a product of empowering women via universal suffrage.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Here's the thing: the findings in all of these studies hing on measuring democracy.

That's not a trivial matter.

That's not a trivial matter.

The Polity measure of democracy runs from -10 (full authoritarian regime - think Saddam Hussein's Iraq) to 10 (full liberal democracy - think Sweden).

In most of the above studies, a pair of countries are considering "jointly democratic" if both have Polity scores >= 6.

In most of the above studies, a pair of countries are considering "jointly democratic" if both have Polity scores >= 6.

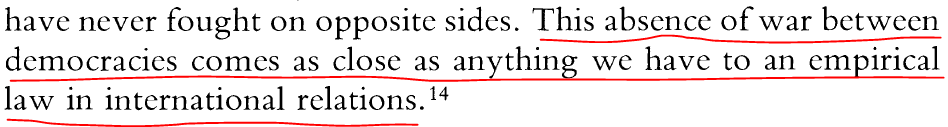

How does Polity acquire that score? A key component in the Polity coding is "Executive Constraints". You can see this by looking at the weights in the codebook

How does the Polity project determine the constraints on a leader (or determine any of the other components)?

Human coding (think of small armies of graduate student RAs)!

Human coding (think of small armies of graduate student RAs)!

But this is where things become tricky, as highlighted in a recent @Journal_of_GSS pieces by @JeffDColgan...

academic.oup.com/jogss/article-…

academic.oup.com/jogss/article-…

The pieces show that the coding of a country's regime type is often influenced by how Americans piece a country: this coder bias can lead to unequal treatment of countries or unequal coding of countries at different times.

Consider this VERY telling (and perhaps damning) passage from Colgan's paper (notable that it deals with Iran, which was the impetus for @McFaul's original tweet)

Needless to say, prominent comparative politics scholars are also not enamored with how Polity codes democracy

https://twitter.com/benwansell/status/1229386394658836480

As you can image, biases in how we code a country's democracy can, in turn, influence our inferences about the democratic peace.

A great piece making this point is by @Idooren in @Journal_IS: a lot of the democratic piece hinges on how we code Germany in 1914

muse.jhu.edu/article/447406…

muse.jhu.edu/article/447406…

There are other critiques of the data that we could discuss, such as "euro-centrism" in our coding of wars...

https://twitter.com/jaylyall_red5/status/1329848448187846656

....or who gets counted as a participant (see Stam, Reiter, and @mchorowitz).

journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117…

The overall point should be clear: the democratic peace relies a lot on how we code our data and what we consider to be a "conflict".

When it comes to the "Democratic Peace" claim, there seems to be a 'there, there', but it's far from solid enough to be an "empirical law", let alone the basis for policy recommendations.

[END]

[END]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh