1. Oil & gas companies still expect the world to consume large quantities of oil & gas in 2050. That view would seem to put the oil giants in conflict with the IPCC.

𝐈𝐧 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐟𝐭𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐞...

@bstorrow eenews.net/climatewire/st…

𝐈𝐧 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐟𝐭𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐞...

@bstorrow eenews.net/climatewire/st…

2. [O]il companies & the IPCC alike rely on a contentious strategy known as negative emissions — the practice of pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. In theory, NETs would buy the world a little more time to phase out the use of fossil fuels ...

3. "[N]one of these models are forecast machines" @DetlefvanVuuren

"It's just an element, a tool to explore different trajectories on the basis of the knowledge we have today & to see what ... might encounter."

Both critics & modelers agree such nuance is often lost

"It's just an element, a tool to explore different trajectories on the basis of the knowledge we have today & to see what ... might encounter."

Both critics & modelers agree such nuance is often lost

4. Many policymakers have concluded that negative emission technologies are necessary for meeting the Paris Agreement's temperature benchmarks, even if modelers themselves are more circumspect.

5. "How great would it be if, rather than just having pathways that kind of put forward technological solutions like BECCS, that we would have pathways that really articulate in clear terms the need for immediate discussions & action towards phasing out fossil fuels" @wim_carton

6. "It's not like, oh, so we can definitely continue exploiting gas or using gas & then we can maybe think about also implementing CCS. No, it is only possible to exploit further [gas] ... if you really meet those key milestones in CCS development globally" @JoeriRogelj

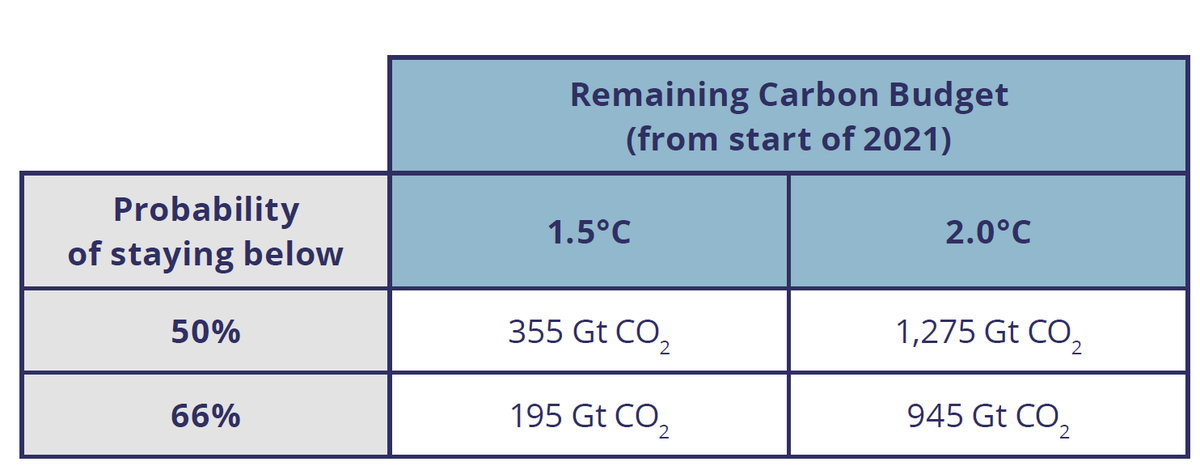

7. [M]odels generally assume that NETs will wipe out anywhere from a few hundred billion tonnes of carbon dioxide to well over a trillion over the course of this century.

8. Oil companies are less reliant on NETs than IPCC.

BP projected BECCS would reduce emissions by 1.5GtCO₂/yr in 2050.

Equinor didn't even model BECCS because it said the technology's future was too uncertain.

The IPCC sees BECCS capturing 3-7GtCO₂/yr in 2050

BP projected BECCS would reduce emissions by 1.5GtCO₂/yr in 2050.

Equinor didn't even model BECCS because it said the technology's future was too uncertain.

The IPCC sees BECCS capturing 3-7GtCO₂/yr in 2050

9. There's a catch, though.

The pathways the models produce aren't necessarily the only ones possible. Most of the time, they're just the cheapest.

The pathways the models produce aren't necessarily the only ones possible. Most of the time, they're just the cheapest.

10. "If people see the UNFCCC, the actual document of the convention, it is stated that climate change mitigation should be pursued in a cost-effective manner" @JoeriRogelj

11. "If we bring this particular problem into the model & let the model try to solve it, then obviously it's part of the least-cost solution to have some of these negative emissions out there" @DetlefvanVuuren

12. "There is a sense that these scenarios are modeling the real world, and that is not necessarily how the world works," said me.

13. "What would it take to deploy hundreds of CCS facilities in the U.S. today? Modelers would say if you had $100-a-ton tax, it would pop everywhere. I struggle to see how you would deploy so much CCS in political reality" said me.

𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐈𝐀𝐌𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠?

𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐈𝐀𝐌𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠?

14. Freelancing now...

What is cost-effective? We assume that this means discounting & optimising costs over the 100 years, assuming everything runs perfectly smoothly & everyone behaves, & we know everything (like costs).

The world is not this nice, unfortunately...

What is cost-effective? We assume that this means discounting & optimising costs over the 100 years, assuming everything runs perfectly smoothly & everyone behaves, & we know everything (like costs).

The world is not this nice, unfortunately...

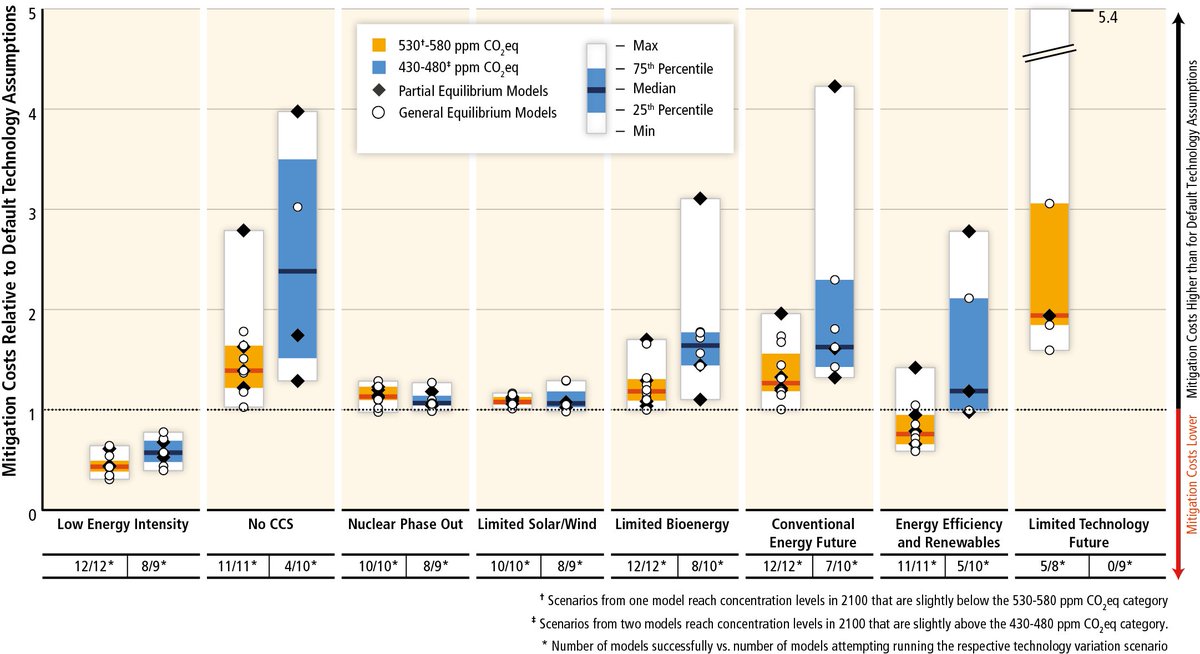

15. A nice illustration comes from @DetlefvanVuuren, where he modelled alternative pathways that didn't require BECCS.

They could not model the cost effectiveness of this pathway. Is it cheaper or more expensive than a BECCS pathway? We don't know!

nature.com/articles/s4155…

They could not model the cost effectiveness of this pathway. Is it cheaper or more expensive than a BECCS pathway? We don't know!

nature.com/articles/s4155…

16. Another nice example is the low-energy demand scenario (LED), where system costs of the demand reductions were not modelled either.

It is hard to trade-off supply-side & demand-side costs. This means we only estimate cost-effective on supply-side.

nature.com/articles/s4156…

It is hard to trade-off supply-side & demand-side costs. This means we only estimate cost-effective on supply-side.

nature.com/articles/s4156…

17. Even the IPCC found that including demand reductions halved costs, noting they could not model the costs of reducing demand. This was in 2014 (AR5)...

ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/

ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/

18. While the UNFCCC argues for cost-effective strategies, the assumption here is that IAMs are actually modelling cost-effective.

Is cost-effective, as defined in an IAM, the same as the real-world definition of cost-effective?

This is the question we need to address...

Is cost-effective, as defined in an IAM, the same as the real-world definition of cost-effective?

This is the question we need to address...

19. ...and should cost-effective include real-world bumpiness. Like justice & equity issues, risk premiums, cost & investment uncertainties, inefficient climate policies (like standards over taxes), election of Trump or Morrison, technical barriers, social barriers, etc, etc.

20. We have to put the scenario outputs in the context of the assumptions used to generate them. And this goes well beyond technology costs, but also has to address overarching structural questions on how the climate problem is framed & implemented in a model.

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh