Historically rules/institutional frameworks for monetary and fiscal policy were motivated by the concern that politicians were BIASED towards too much deficit increase, inflation, living for the moment, etc.

Certainly some politicians are biased in the traditional manner but many have the opposite bias--they want excessive deficit reduction at the wrong times and oppose expansionary policies by the Central Bank too.

Instead we should motivate rules/institutional frameworks by the concern that politicians are INEFFICIENT in the statistical sense of sometimes delivering/wanting too much and other times too little often for random reasons like the timing of an election, the incumbent party, etc

Both the BIAS and INEFFICIENT perspectives get you roughly the same answer on central banks but for different reasons. From the INEFFICIENT perspective, central bank independence is also about, eg., protecting technocrats at the ECB from German politicians pushing contraction.

The two perspectives give you different answers on fiscal policy. If you are concerned about the inefficiency of the political system you can either try to get politicians to behave more like central banks (impossible) or have more automatic rules for fiscal policy (possible).

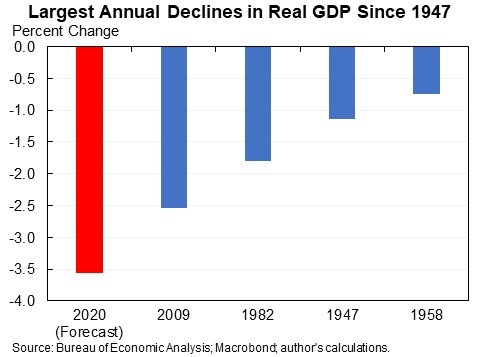

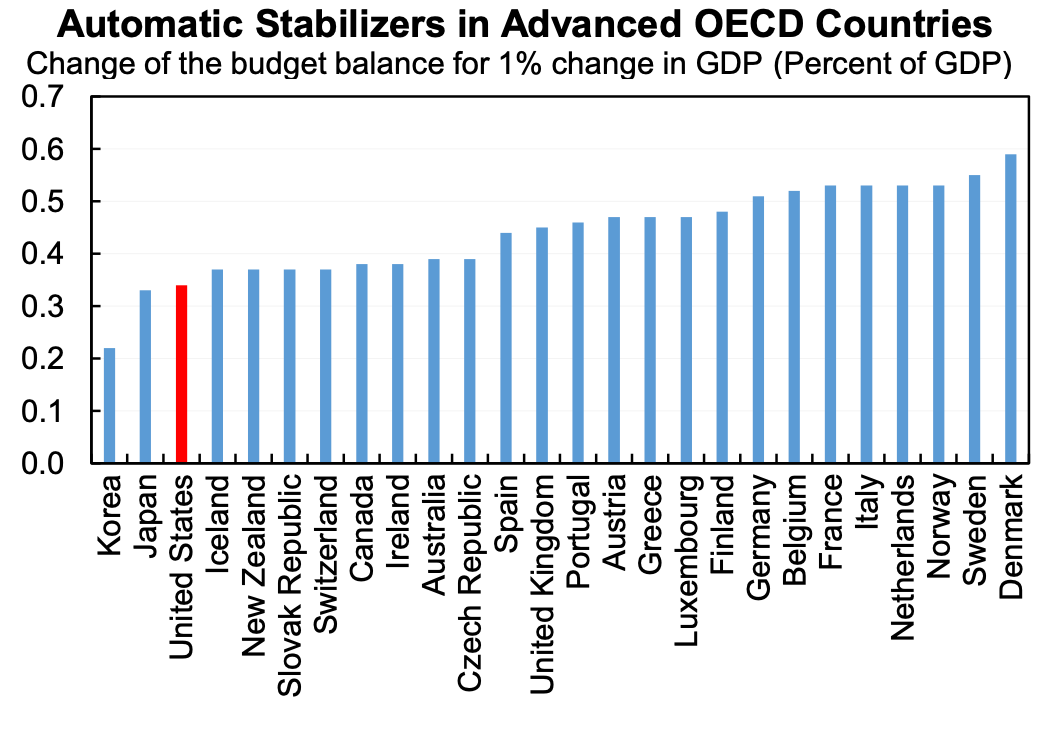

In the US the most important set of rules is to expand automatic stabilizers because they are relatively small in our economy as you can see. Make state aid, unemployment and more contingent on the unemployment rate as I advocate in today's @wsjopinion. wsj.com/amp/articles/b…

Europe has better automatic stabilizers but a bad habit of reversing them unnecessarily during downturns (fortunately not this time). So what it needs are fiscal rules that are more symmetric, not just tilting against excessive deficits but also against excessive deficit redn.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh