#MalcolmX and the #Arab World, a thread for #BlackHistoryMonth . Based on my "My Heart Is in Cairo: Malcolm X, the Arab Cold War, and the Making of Islamic Liberation Ethics," @JournAmHist

#AfricanaReligions #blkaarsbl #AfAmReligion #BlackLivesMatter #Religion #Black #African

#AfricanaReligions #blkaarsbl #AfAmReligion #BlackLivesMatter #Religion #Black #African

From the late 1950s until 1965, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz developed and maintained consequential relationship with Arab and Arab American leaders. His message to them, whether as #NationofIslam leader or Sunni convert, was: Islam requires you to support Black Liberation.

Arab Americans like Aliya Ogdie Hassen (@saladinahmed 's great grandmother) believed that Muslim unity was necessary for self-determination and human rights. Hassen was the liaison between Malcolm X and the Federation of Islamic Associations.

lebanesestudies.ojs.chass.ncsu.edu/index.php/mash…

lebanesestudies.ojs.chass.ncsu.edu/index.php/mash…

From 1959 onwards, Arabic-speaking Sudanese Muslims such as Ahmed Osman and Malik Badri played a key role in convincing the leader that the Black and Arab political interests were aligned. Check out @HishamAidi 's doc.

vimeo.com/394471323

vimeo.com/394471323

The Federation of Islamic Associations had been founded by Midwestern Muslims like Abdullah Igram, but by the time Malcolm X was ready to separate from Elijah Muhammad, it was led by Egyptian Mahmoud Shawarbi in New York. Shawarbi arranged for Malcolm's residency in Egypt.

Because of its roots in the Syrian American Midwest, which was both Shia and Sunni, the FIA was not a sectarian organization. And Malcolm X's connections included Sunni and Shia Muslims.

muse.jhu.edu/article/479512…

muse.jhu.edu/article/479512…

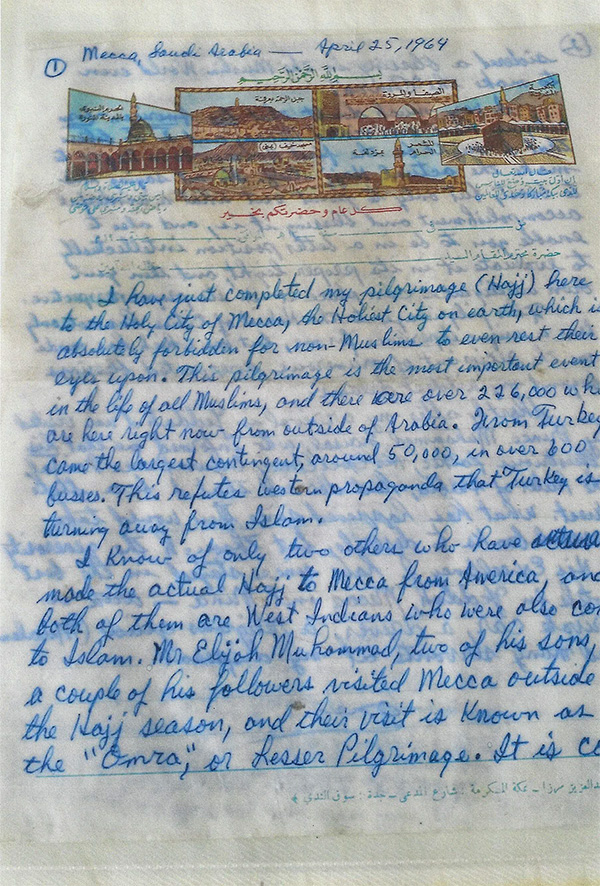

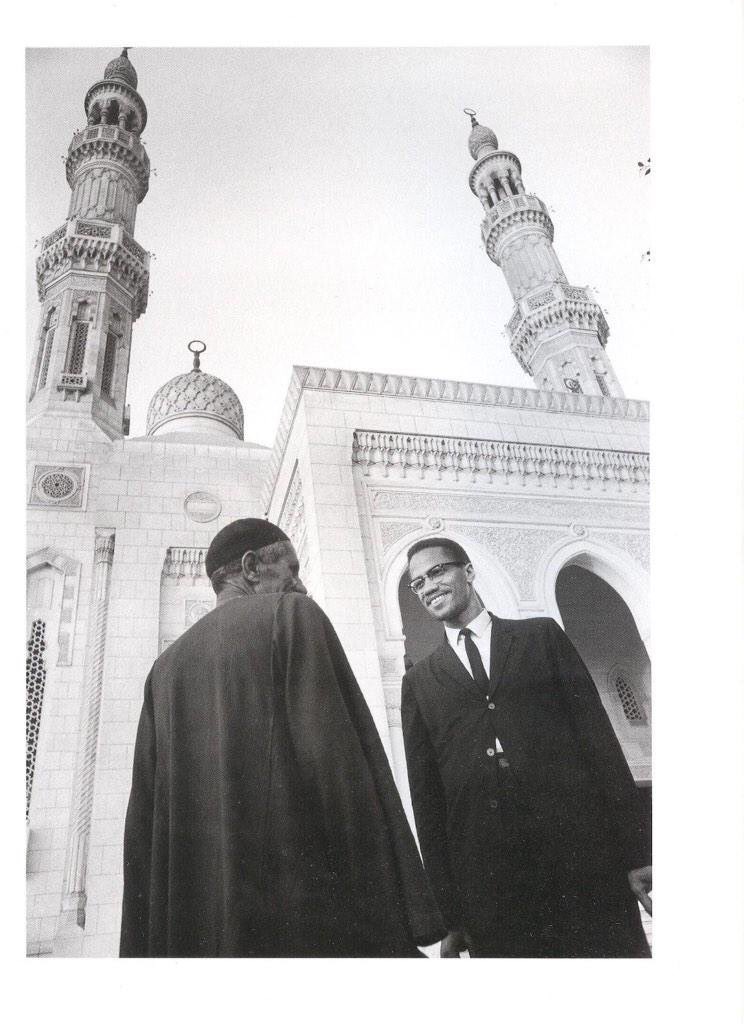

Similarly, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz pursued connections with Arab Muslims across the lines of the Arab Cold War, which was being fought between Saudi Arabia and Egypt in Yemen. In 1964, he spent half the year abroad, much of that in Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Malcolm X was friends with people who were enemies of one another, or at least people who did not get on well. For example, in the Autobiography he appreciates the help of Abd Al-Rahman Azzam, architect of the Arab League who fell out of favor with Gamal Abdel Nasser.

In the 1964, he takes ijazas or diplomas in Islamic missionary work from both Egypt's Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs and the University of Medina in Saudi Arabia. Malcolm X cultivates allies across the ideological spectrum of Arab politics.,

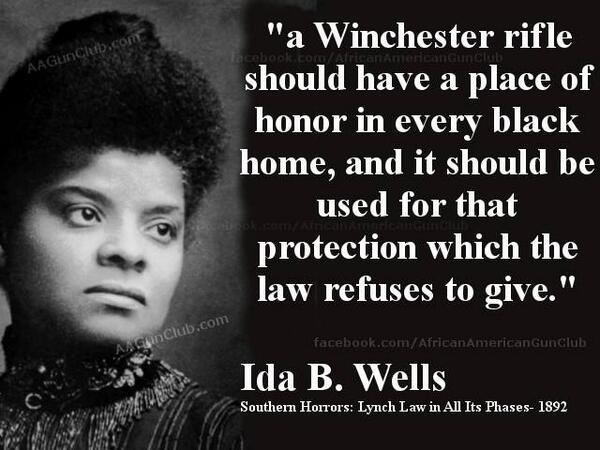

But Malcolm X is consistent and uncompromising when it comes to his message about Black liberation. He has no use for Muslim Brothers' leader Said Ramadan's claim that if everyone will convert to Islam, racism would disappear. He views racism as political and economic problem.

In the popular memory of many us, from many places, we imagine Malcolm X's moment on Mt. Arafat during his hajj pilgrimage, as a moment of supreme religious meaning, and it was. But reading El-Hajj Malik's own words, especially in his diaries, reveal something else:

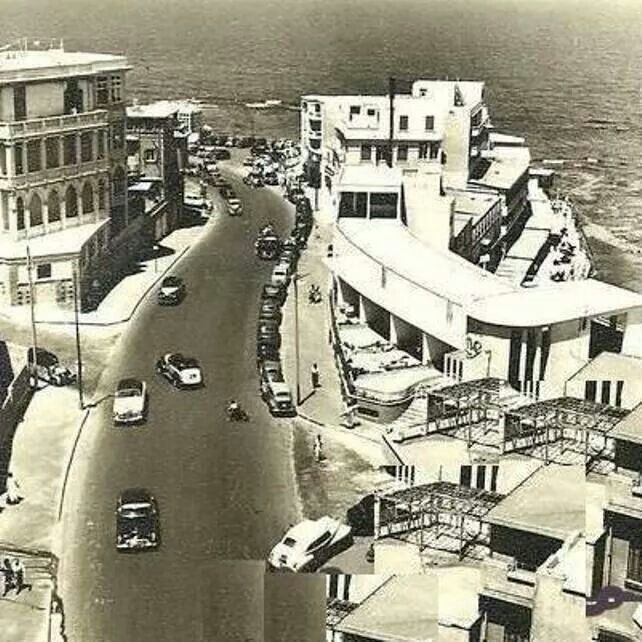

There were other transcendent spiritual moments during his journeys abroad. One was in Ibadan, when Nigerian called him the Omowale, the son who has come home. Another, less well known, was in Alexandria.

On August 2, 1964--and scholars of Malcolm X need to elevate this moment from its relative historiographical obscurity--Malcolm X addresses the Abu Bakr Siddiq Camp for Muslim Youth. "This affair," he wrote in his diary, "impressed me more than mu trip to Mecca." !!!

"Youth from everywhere, faces of every complexion, representing every race and every culture... all shouting the glory of Islam, filled with a militant revolutionary spirit and zeal." This was much better than the "diplomacy" of politicians, he said. Males and females, all....

"jumped to their feet shouting beautiful slogans of support and unity in our common struggle." They were unambiguous in supporting anti-colonialism and human rights for all, including African Americans.

These youth represented the Muslim solidarity with real Black liberation.

These youth represented the Muslim solidarity with real Black liberation.

When Malcolm X returned home to New York from his residency in both Egypt and Saudi Arabia, as well as his travels, he resumed his leadership duties, and he wrote two important letters--one to Egypt's Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs, one to the Saudi-led Muslim World League.

His letter to Egyptians, written on November 30, 1964, explained that he hoped the SCIA understood his "cementing good relationships" with the MWL. But, he assured them, "My heart is in Cairo. And I believe the more progressive. . . forces in the Muslim world are in Cairo."

This #BlackHistoryMonth , we should celebrate the many sides and many interpretations of Malcolm X's legacy. But I hope one of them is that his idea that religion is not true religion unless it strives for justice in the here and now. And.....

Religion is more hindrance than help unless it confronts the legacy of anti-Black hatred and oppression at the heart of the modern world. For him, the fight for Black dignity was inseparable from the struggle against white supremacy and colonialism. We need his voice.

Want to listen to the podcast version of this? Check out Ed Linenthal and me at the JAH Podcast:

jahpodcast.com/podcast/201512…

jahpodcast.com/podcast/201512…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh