🚖 #Uber drivers are workers, the UK #SupremeCourt confirms. Major legal & labour market implications - let's take a detailed look at this landmark judgment (long-ish 🧵, the short take is here 👉

https://twitter.com/JeremiasPrassl/status/1362700749709471748)

#Uber drivers are workers – entitled to the minimum wage (& other key employment rights) whenever they’re logged on. Lord Leggatt gives the powerful unanimous judgment of the court

The facts are well-known by now – but important to remember the sheer scale of this decisions: in 2016, @Uber employed over 30,000 drivers in London alone (40k across the UK).

Succinct summary of the @Uber business model… app, matching algos, fare setting and Uber’s share, prohibition on exchanging contact details, rating system [6] – [13]

… and the worker experience: onboarding, access to the app, providing your own phone, car, fuel, flexibility to pick working times [14]-[16]

... but also strict performance standards and tight control [17] – including over cancellation and acceptance rates (these will be crucial, later)

Onwards to the written documentation: not a worker contract, Uber claims, but ‘Partner Terms’ and ‘Services Agreements’ 🤔

Drivers are defined as ‘Customers’, Passengers as ‘Users’ – and ‘Customer acknowledges and agrees that Uber BV does not provide transportation services’. [24] The ET had some choice phrases for this sort of fiction...

There follows a quick analysis of the passenger agreement [27] and the licensing regime [30], which Uber had sought to rely on at various points …

… and an pithy summary of what this is all about: the statutory core of rights workers are entitled to, incl minimum wage, annual leave, and working time protection.

A quick history of the litigation at [39]-[40] – see for an earlier thread summarising what happened between 2015 and 2021, here

https://twitter.com/JeremiasPrassl/status/1362690317904973827

This is the crux of the issue: do drivers perform services for Uber, or (as the contracts suggest) directly for passengers with the ‘platform’ merely acting as an ‘agent’? [42]

#Uber’s answer is straightforward: look to the written documents and those documents alone; the courts and tribunals below had no justification to disregard their clear and unambiguous terms [44]

Lord Leggatt is not impressed: @Uber struggles ‘even if the correct approach … were simply to apply ordinary principles of the law of contract and agency’

‘It is reasonable to assume, at least unless the contrary is demonstrated, that the parties intended to comply with the law.’ So ‘the only contractual arrangement compatible with the licensing regime is one whereby Uber … accepts private hire bookings as a principal’

In any event, ‘there appears to be no factual basis for Uber’s contention that Uber London acts as an agent for drivers when accepting private hire bookings’ [49]

… save to highlight the fact that L Leggatt’s conclusion is very similar to the approach taken by the CJEU & AG @maciejszpunar in Elite Taxi (albeit in a different regulatory context): Uber’s business model is more than just running an app.

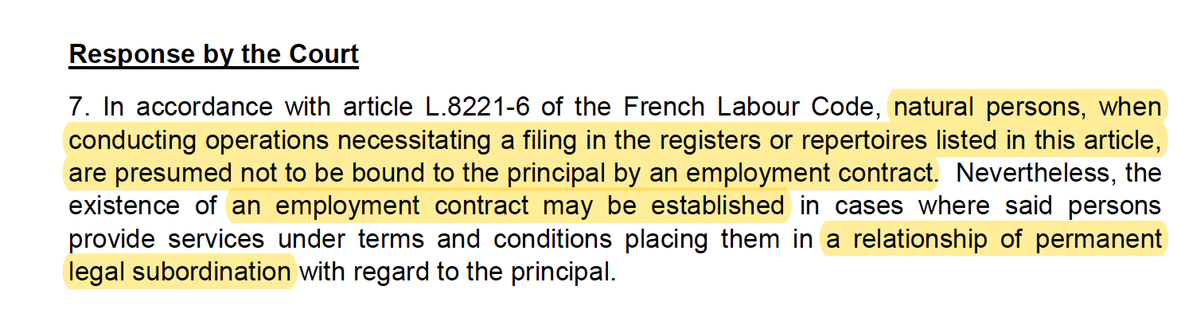

On we go to the core employment law issue – and the key Q as to when courts are entitled to disregard written agreements. The key case here is Autoclenz (2011):

A key upshot of which is the principle that employment contracts cannot be treated like any ordinary commercial agreement

In certain scenarios, courts must look to the ‘reality of the relationship’ between the parties, including in particular the ‘relative bargaining power of the parties’, to glean the true nature of the agreement

🚨 What’s at stake, L Leggatt explains, are not contractual rights – but statutory entitlements created by legislation.

We should therefore focus on the general purpose of the legislation in question – which is ‘to protect vulnerable workers’

Employers’ control and worker’s dependence ‘give rise to a situation in which [employment] relations cannot safely be left to contractual regulation’ (see also a nice shoutout to @DavidovGuy's excellent book!)

💫 Paragraph [76] is destined to enter the pantheon of employment law – contractual interpretation alone ‘would reinstate the mischief which the legislation was enacted to prevent’ 💫

The law cannot ‘accord Uber power to determine for itself whether or not the legislation designed to protect workers will apply to its drivers.’ [77] 🛑✋

How, then, should the worker test be applied? ‘view the facts realistically and … keep in mind the purpose of the legislation‘ [87]

📢📢 Flexible work is NOT incompatible with worker status! This cannot be emphasised enough (though the ref to Windle is a bit unfortunate)

And so the ET was right to find that Uber drivers are workers. Five reasons are highlighted in particular: 1/ Uber fixes rates and its cut

3/ once logged on, #Uber constrains driver choice by deliberately creating information asymmetry, and exercises tight algorithmic control (through ratings, cancellation penalties, …)

4/ ‘#Uber exercises a significant degree of control over the way in which drivers deliver their services’

5/ Uber strictly controls drivers’ communications with passengers, ‘takes active steps to prevent drivers from establishing any relationship with a passenger capable of extending beyond an individual ride’

Taken together – and this is crucial – the setup denies any opportunity for entrepreneurship or individual business development

Another frequently deployed red herring is strongly dismissed at [102] – compliance with other laws is not an excuse or defence when it comes to employment status 🎣

There follows a discussion of cases including booking agents (a key issue in the CA) and minicab drivers – none of which are accepted as supporting Uber’s case.

And there we are: after 4 ½ years, the ET decision is confirmed at the fourth and final instance: worker status was ‘the *only* conclusion which the tribunal could reasonably have reached.’ 🏆

Which leaves us with the working time issue: ‘during what periods of time were the claimants working?’ 🕰

The ET (correctly) decided that working time included whenever the app was on & drivers are ready and willing to accept trips

#Uber strongly disagrees, even though it forcibly logged drivers off for refusing rides:

But that’s the very point: ‘exclusion from access to the app was designed to operate coercively … as a penalty for failing to comply with an obligation to accept a minimum amount of work. ‘

A powerful judgment, promising consistency and clarity. We should also pay tribute to brilliant counsel on both sides, incl @DinahRoseQC & Fraser Campbell @BlackstoneChbrs; @galbraithmarten & Sheryn Omeri @CloistersLaw; and Oliver Segal QC and @MelanieTether @OldSqChambers

Here is the link to the full text - supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uks… . And make sure to check out @JasonBraier 's excellent thread!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh