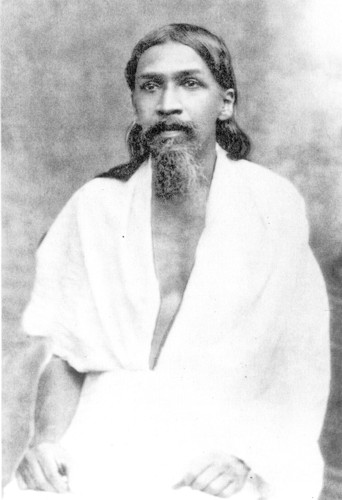

The Uncolonized Mind: Aurobindo

If Kipling was culturally an Indian child who grew up to become an ideologue of the moral and political superiority of the West, Aurobindo was culturally a European child who grew up to become a votary of the spiritual leadership in India.(1/17)

If Kipling was culturally an Indian child who grew up to become an ideologue of the moral and political superiority of the West, Aurobindo was culturally a European child who grew up to become a votary of the spiritual leadership in India.(1/17)

If Kipling had to disown his Indianness to become his concept of the true European; Aurobindo had to own up his Indianness to become his version of the authentic Indian. Though Aurobindo symbolized a more universal response to the splits that colonialism had induced. (2/17)

Aurobindo Ackroyd Ghose- the Western middle name was given by his father at birth- was the third son of his parents. The Ghoses were urbane Brahmos from near Calcutta and fully exposed to the new currents of social change in India. (3/17)

His father, Krishnadhan, a doctor trained in England, was well known among his friends and relatives for his aggressively Anglicized ways. He forbade his children to learn or speak Bangla; even at home, they had to converse in English. (4/17)

For some reason, young Aurobindo was the favored object of his father’s zealous social engineering. Krishadhan took the greatest care that nothing Indian should touch this son of this. (5/17)

Aurobindo’s mother, Swarnalata, though, was an ‘orthodox’ Hindu, and she didn’t fully relish the Western manners of her husband. Nor must she have enjoyed the charade of communicating through English in the family. (6/17)

However, what disturbed human relations in the family more than the oppression of language was the illness Swarnalata who fell prey to early in Aurobindo’s life. Called hysteria by her contemporaries, she gradually became more and more ‘unmanageable’. (7/17)

Either as a response to the environment at home, or as a response to her mother's condition, young Aurobindo showed signs of mutism and interpersonal withdrawal, which his admirers were to later read as an early sign of spirituality. (8/17)

When five, Aurobindo was sent to a Westernized, elite convent at Darjeeling with an English governess who served as a surrogate mother. His co-students there were mostly white. English was the sole medium of instruction and only means of communication outside school hours. (9/17)

The resulting sense of exile found expression, and even at that age, in a statement made in the third person;

“In the shadow of the Himalayas, in sight of the wonderful snow-capped peaks, even in their native land they were brought up in alien surroundings.” (10/17)

“In the shadow of the Himalayas, in sight of the wonderful snow-capped peaks, even in their native land they were brought up in alien surroundings.” (10/17)

When Aurobindo was seven, his father took him to England and left them there. He was now exposed, not to the Westernized lifestyle of Indians, but the Western ways of the English. One Sunday, Mrs. Drewett who was Aurobindo’s care-taker, managed to get him duly baptized. (11/17)

During his days with the Drewett's & later at an elite school, Aurobindo was now exposed to Greek & Latin. He took a scholarship at King’s College & did brilliantly, winning all the prizes. He learnt French, some German, and Italian. Yet there was a rebellion in the air. (12/17)

For years he had been taught to view England as an ideal society; now England was re-invoking his early anxieties associated with the West. He began to look for alternative ways for handling the Occident & to defy the model of success associated with the Anglicism of his father.

Thus, after taking the first part of the Classical Tripos with a first-class, Aurobindo did not take the degree. He did very well in the ICS exam, he missed the riding test & got himself disqualified, knowing well that ‘his father was very particular about the exam’.(14/17)

Finally, he delivered a few fiery nationalist speeches at the Indian Majlis in Cambridge & got involved with a secret society pursuing the cause of Indian freedom. And to symbolize his break with the West, he dropped the Ackroyd from his name. (15/17)

He started working out on the rudiments of a political ideology, which was to be built around a form of populism in which ‘the proletariat’ was ‘the real key to the situation’ and around a mythography of India as 'a powerful mother, Sakti'. (16/17)

This imaginary he has borrowed from Bankim Chandra Chatterji. Aurobindo admired Bankim as much for this as for the hope Bankim’s work gave of being able to drive out the English language, his father’s beloved language, from India & install his mother-tongue at its place. (17/17)

~ 𝘚𝘦𝘭𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮, 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘐𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘌𝘯𝘦𝘮𝘺: 𝘓𝘰𝘴𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘰𝘧 𝘚𝘦𝘭𝘧 𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘳 𝘊𝘰𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘪𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘮 𝘣𝘺 𝘈𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘕𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘺 [𝘌𝘯𝘥]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh