“How do open-ended questions improve interpersonal communication?”

TL;DR: They do not.

Let’s explore a common #communication assumption about 'open' and 'closed' questions with some data to see what they look like, and what they do, in real interaction.

1. Thread. 🧵

TL;DR: They do not.

Let’s explore a common #communication assumption about 'open' and 'closed' questions with some data to see what they look like, and what they do, in real interaction.

1. Thread. 🧵

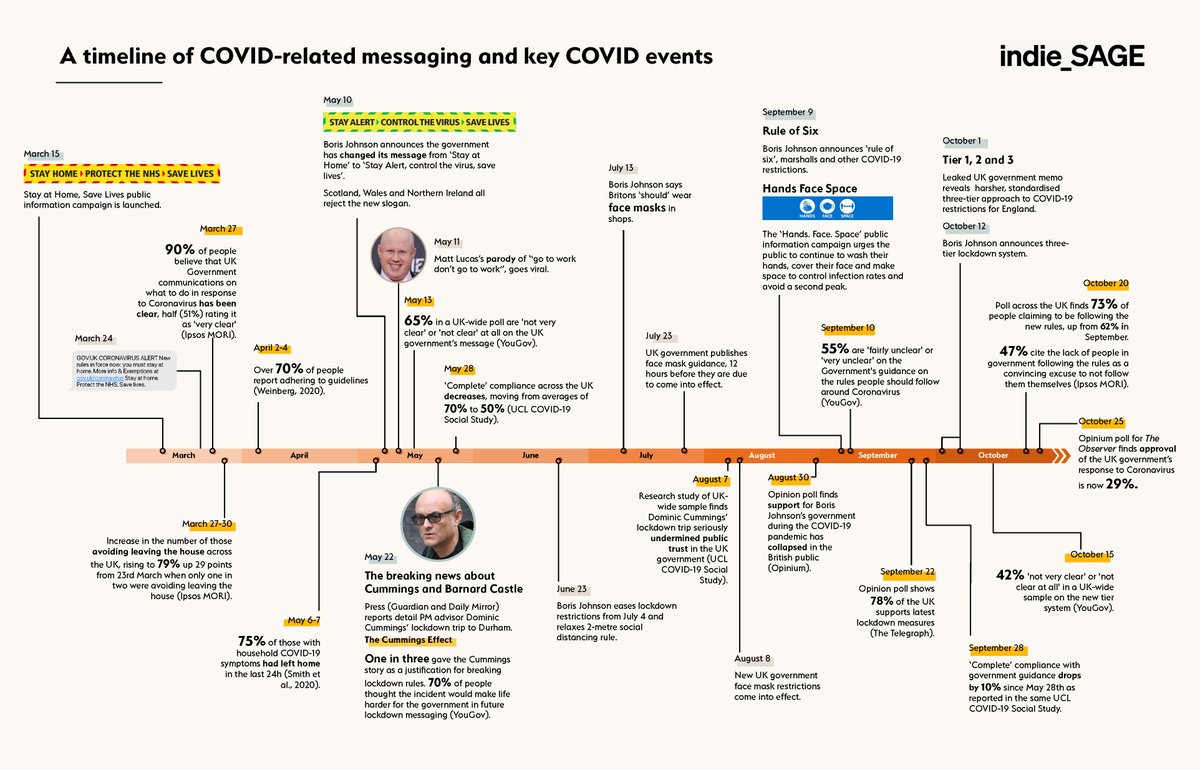

2. Google "open and closed questions” and you’ll find loads of articles and (often written or hypothetical) examples about them - tweet 1 is just one of many.

As @d_galasinski pondered recently: “I wonder who is responsible for fetishising open questions.”

As @d_galasinski pondered recently: “I wonder who is responsible for fetishising open questions.”

3. When we examine questions as they are actually used - ‘in the wild’ - we find that yes/no (‘closed’) questions routinely receive more than ‘yes/no’ in response.

And just because a question is ‘open’ doesn’t mean it'll be answered.

Let’s see some examples.

And just because a question is ‘open’ doesn’t mean it'll be answered.

Let’s see some examples.

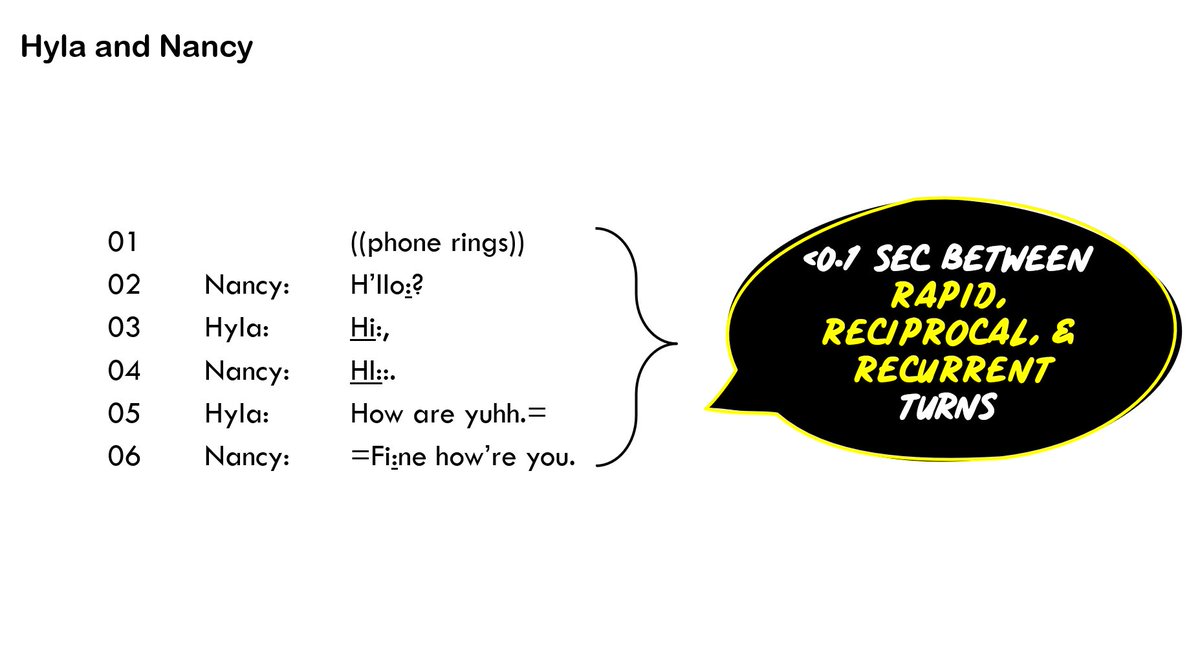

4. Here's another example from a group of friends chatting.

[#EMCA researchers use the 'Jefferson' system for transcription - to find out more, see @alexahepburn @BoldenGalina's book 'Transcribing for Social Research'.]

[#EMCA researchers use the 'Jefferson' system for transcription - to find out more, see @alexahepburn @BoldenGalina's book 'Transcribing for Social Research'.]

5. Just saying 'yes' or 'no' - even when the question requires 'yes' or 'no' - can even seem a bit rude ...

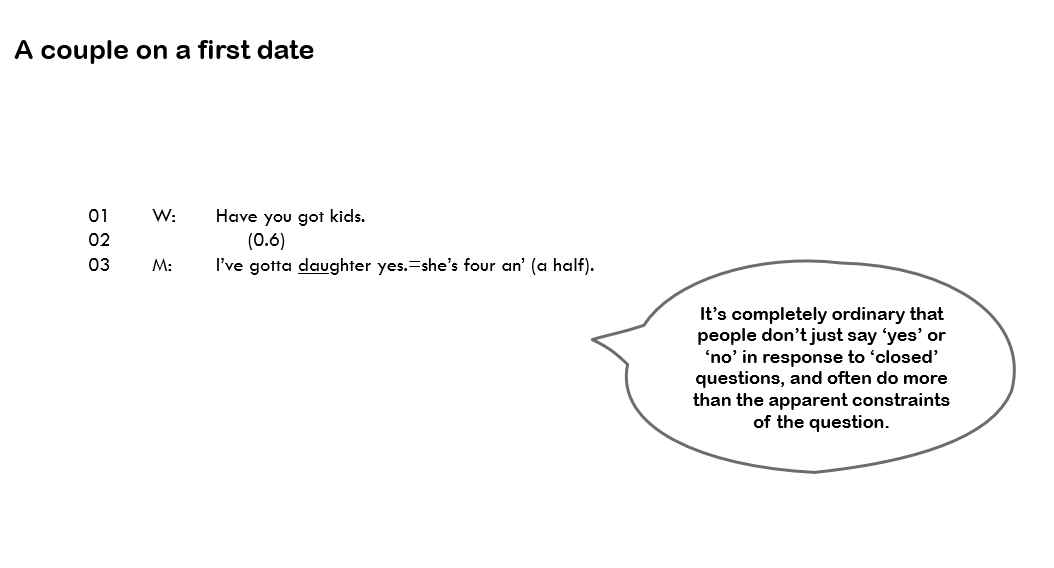

6. Here's an example from a first date. The couple has been talking about what they like in a partner.

If someone answers an 'open' ('wh-') question with a a closed response (line 11), perhaps the date isn't going well... 😬

If someone answers an 'open' ('wh-') question with a a closed response (line 11), perhaps the date isn't going well... 😬

7. Why do people so regularly give more than a 'closed' response to an apparently 'closed' question?

When we look at real talk, rather than imagine talk, it seems pretty ordinary to do so (as in this example from research with @S_Parslow @MFlinkfeldt)

When we look at real talk, rather than imagine talk, it seems pretty ordinary to do so (as in this example from research with @S_Parslow @MFlinkfeldt)

8. In response to a 'closed' question from the patient, the #GP receptionist doesn’t just say ‘no’.

Her response conveys ‘no’ while ALSO providing an account for not saying ‘yes’ (as in this example from research with @rein_ove @symondsjon) - because the question is a request.

Her response conveys ‘no’ while ALSO providing an account for not saying ‘yes’ (as in this example from research with @rein_ove @symondsjon) - because the question is a request.

9. Here's an example of rapidly repeated responses to a 'closed' question - again, doing more than required and doing it early (it's from a study of antenatal consultations conducted with @MagnusHamann @DoctorDot2 @jayne_wagstaff)

11. In this example, the cafe staff apparently doesn't understand that people make requests by asking a yes/no closed question 🤔

12. Of course, there are always survey questions, where responses can be constrained by the design of the form, like in these examples from my friends @typeform

13. Politicians often resist answering 'closed' questions, like this famous example from 1997 in which Jeremy Paxman asks Michael Howard the same yes/no question - "Did you threaten to overrule him?” - 14 times 🤔

14. Since #LineOfDuty is back, it's timely to also show that some questions will not be answered no matter what the design of the question.

15. Here’s an article by @LucasSeuren & Mike Huiskes showing how ‘very closed’ questions readily get 'open' long answers.

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

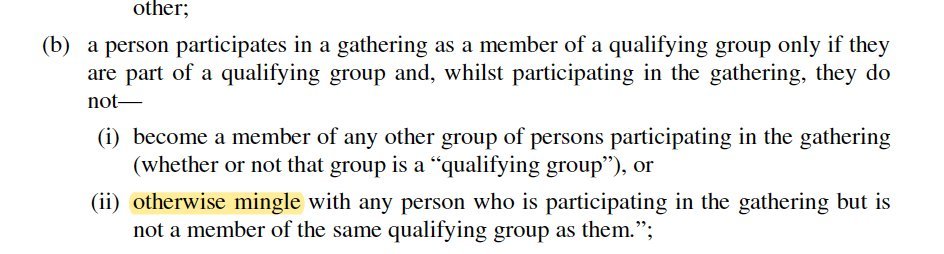

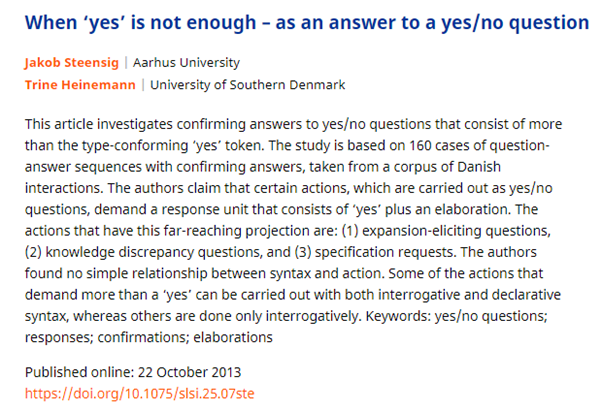

16. "When yes is not enough":

An article by @JakobSteensig & Trine Heinemann shows that “certain actions, which are carried out as yes/no questions, demand a response unit that consists of ‘yes’ plus an elaboration.”

An article by @JakobSteensig & Trine Heinemann shows that “certain actions, which are carried out as yes/no questions, demand a response unit that consists of ‘yes’ plus an elaboration.”

17. Finally, grammar and question design can save lives, as this call to 911 shows.

The dispatcher asks 'yes/no' questions to enable the caller to get emergency help without asking for it.

The dispatcher asks 'yes/no' questions to enable the caller to get emergency help without asking for it.

18. In sum:

Questions are vehicles for different actions. They are always embedded a sequence. They're not simply 'open' or 'closed'.

To read more research on naturally occurring interaction, visit emcawiki.net/EMCA_bibliogra…

End 🧵

Questions are vehicles for different actions. They are always embedded a sequence. They're not simply 'open' or 'closed'.

To read more research on naturally occurring interaction, visit emcawiki.net/EMCA_bibliogra…

End 🧵

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh