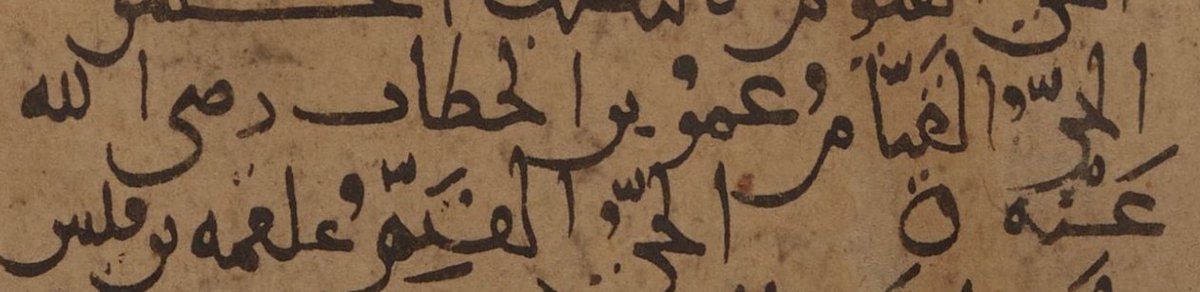

In recent months I've been looking at a specific group of Quranic manuscripts written in the very common B.II style. Today I decided to look at the size of the folios and their height and width. The outcome surprised me but is really cool, so here's a thread! 🧵

While the corpus of 22 manuscripts I'm looking at is all written in the same style, usually have 16 lines to the page, the actual sizes of the parchment folios differ radically from manuscript to manuscript. The smallest, Arabe 399 is 42 by 73 mm (!), the largest 310 by 410 mm.

The most typical size is around 150 x 205 mm, but what is the relationship between these vastly differing sizes? Is there any rhyme or reason?

I decided to plot the sizes out as a scatterplot , and the result was striking. They form an almost perfectly straight line!

I decided to plot the sizes out as a scatterplot , and the result was striking. They form an almost perfectly straight line!

This means there there is a very clear and simple linear relation between the height and the width of any folio. There was only one clear outlier, MS Add. 743.3. This is a folio that has been reframed, so its exact measurements are not entirely clear, and may have fit.

Once one removes MS Add. 743, fitting a linear regression to it, shows just how close the page dimenions are to a perfectly linear relation.

The formula for this line is width = 1.22*height +28.21 mm.

The formula for this line is width = 1.22*height +28.21 mm.

That's almost exactly a 6:5 (= 1.2:1) aspect ratio, with a fixed additional ca. 28 mm, regardless of the size of the manuscript. So what is that additional 28 mm about? I think this was a conventional size adhered to to form the gutter.

When folios are bound, the very innermost section of a page will not be readable because it is bound together in that place. The typical unit equivalent to an 'inch' is the ʾiṣbaʿ (literally "finger") which is 1/24th of a ḏirāʿ (an ell).

Throughout history and throughout the Islamic world the size of the ʾiṣbaʿ has varied from around 21 mm to 31 mm, so we can say approximately 25mm is the size of an ʾiṣbaʿ. An idealized formula width = (6/5)*height + 25 is still an excellent fit with the data (green).

It seems then, that the people who cut the parchments that were used to make B.II style manuscripts (which seem to have Basra, around the 2-3rd c. AH) adhered to a simple geometric rule:

The page width should be one fifth longer than the height + 1 ʾiṣbaʿ for the gutter.

The page width should be one fifth longer than the height + 1 ʾiṣbaʿ for the gutter.

I thought this was really neat, and it makes one hopeful that we can uncover more correlations between production practices like page size with other script styles used to produce Quranic manuscripts!

You may have noticed that in the in the plot the y-axis is width and the x-axis is height, which is a little bit weird. But the rule adhered to seems to be that width is a function of height and not the other way around.

(otherwise you get: height = (5/6)*width - 21)

(otherwise you get: height = (5/6)*width - 21)

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh