In the Quran, God is referred to in three places (Q2:255; Q3:2; Q20:111) as al-ḥayy al-qayyūm "The Living, The All-Sustaining". ʿUmar ibn al-Ḫaṭṭāb , the second Islamic caliph, is attributed as reading al-Ḥayy al-Qayyām, a reading which has an interesting biblical parallel.

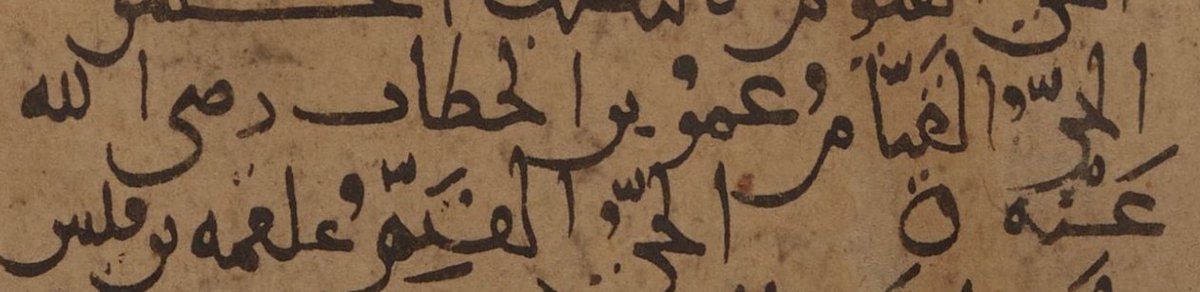

This reading shows up in the non-canonical reading collections like Ibn Ḫālawayh, but also in Kufic manuscripts, see previous tweet where a vocalizer has added a yellow ʾalif to indicate al-ḥayy al-qayyām.

The specific al-ḥayy al-qayyām bring to mind a verse from Aramaic part of the Hebrew bible, Daniel 6:27 (thanks for alerting me of it@bnuyaminim!) it reads: הוּא אֱלָהָא חַיָּא וְקַיָּם לְעָלְמִין: hu ʾɛ̆lāhā ḥayyā wqayyām lʿålmīn "he is God, living and steadfast forever".

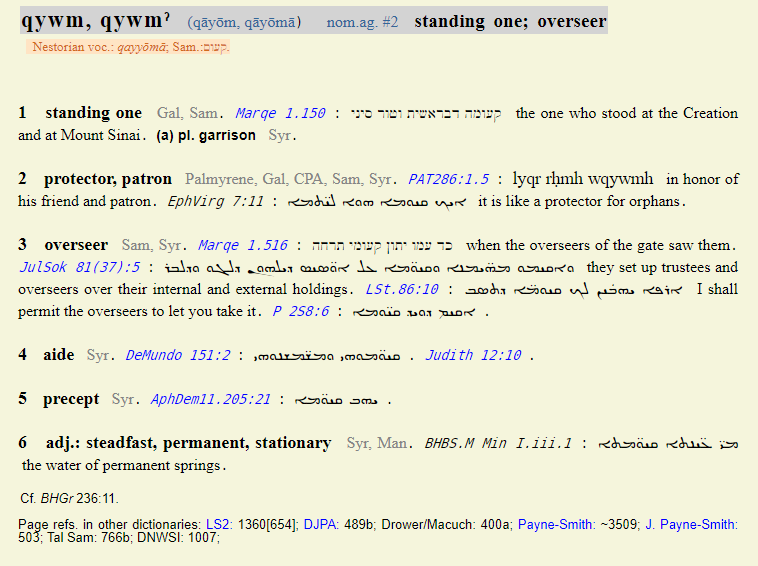

The same formula is also found elsewhere in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic. For example this magic bowl speaks of: לאלהא חיא וקימא <l-ʾəlāhā ḥayyā w-qayyāmā "the living and stadfast God"

cal.huc.edu/showachapter.p…

cal.huc.edu/showachapter.p…

In other words, the epithets used there have the exact same form as the form attributed to ʿUmar. This is unlikely to be a coincidence. Clearly this collocation was known among Aramaic speakers, and had been borrowed wholesale into Arabic.

The form qayyām, in Arabic itself is quite unusual. As the root is q-w-m, we would rather expect **qawwām. This shift of medial w to y is typical for Aramaic, so the form allegedly used by ʿUmar is clearly an Aramaic loanword, and matches the biblical use.

The canonical form of the epithet qayyūm, having a CayCūC pattern, likewise looks rather unusual as an Arabic word. But the closest match qāyōm, would probably be expected to be borrowed as qāyūm. The form also is not clearly associated with an epithet of God (unlike qayyām).

The canonical form is clearly the form that most obviously fits the Uthmanic Rasm, and it present somewhat of an etymological conundrum. But the reading by ʿUmar clearly has a parallel as an Aramaic Jewish formula, and thus seems to be a genuinely ancient pre-Uthmanic reading.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh