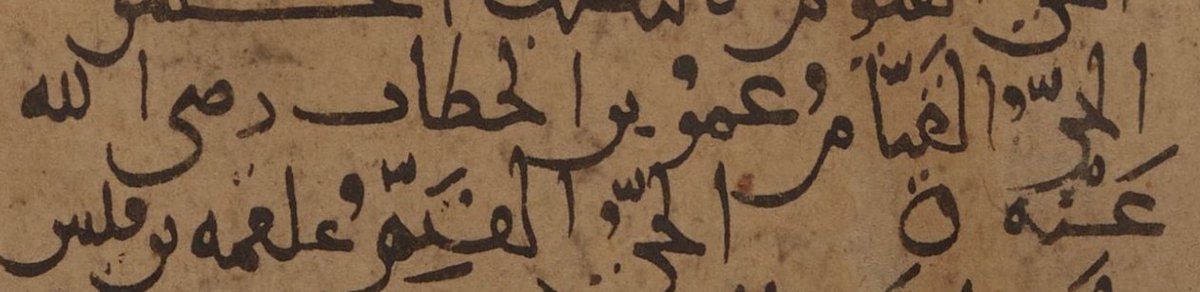

While there are hundreds of differences between modern print editions of the Quran and ancient manuscripts, this is not the case if you compare ancient manuscripts. They agree with each other in many non-trivial ways. I've done a quick a critical edition of Sūrat al-Raḥmān.

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1389227547808968712

First image is some explanation on my sources and decisions that I have taken. Second image is the critical edition, which required only 12 notes in the critical apparatus. Many these deviations are typical only of later manuscripts. In the early centuries the text is very stable

At some point, some of the rasm is innovated, and in the eastern Islamic world the Uthmanic rasm is dropped altogether in favour of Classical Spelling. But before that the text transmission is remarkably stable.

This was done quickly maybe there's still some mistakes.

This was done quickly maybe there's still some mistakes.

Now for an exercise to the readers: What deviations do you see from the printed Quran as we have it today? There would be quite a few more notes if we would have to include all its deviations in comparison to these ancient manuscripts.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh