I previously did a thread on what the disappearance of LGE means. I’ll share two cases to illustrate some of my thoughts…

https://twitter.com/cshenoy3/status/1194307122017849345?s=20

The first is a case of Desmoplakin cardiomyopathy that we published a few years ago:

ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CI…

ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CI…

A CMR 4 months later showed a near resolution of the anteroseptal/anterior/anterolateral LGE (red arrows). The inferior LGE (blue arrow) that did not disappear matched the fat seen on cine images.

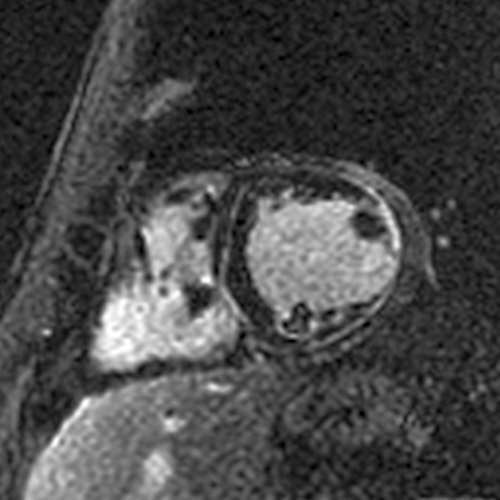

All short axis LGE images at the time of the acute myocarditis.

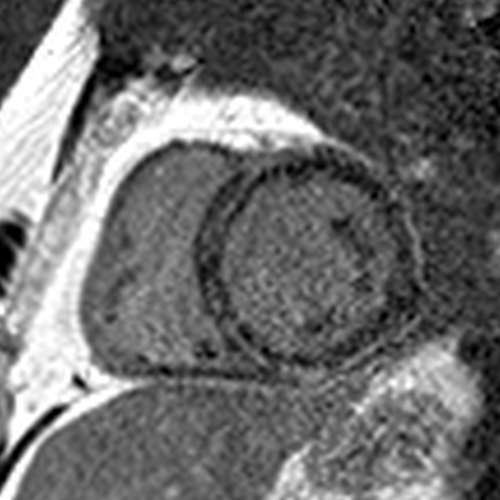

All short axis LGE images 4 months later showing a significant decrease in the LGE.

Next case - this patient had a STEMI with chest pain, anterior ST elevations, and elevated troponin. Coronary angiography showed disease in the LAD that was felt to be the culprit and was treated with 3 stents.

CMR during the hospitalization for the STEMI showed a patchy MI in the LAD territory. CMR 6 months later showed no LGE. Small/patchy MIs can also disappear.

All short axis LGE images at the time of the STEMI.

All short axis LGE images 6 months later showing the disappearance of the LGE.

This JACC Scientific Expert Panel article led by @Borjaibanez1 includes a nice cartoon explaining why patchy MIs can “disappear”.

jacc.org/doi/full/10.10…

jacc.org/doi/full/10.10…

Bottomline – The disappearance of LGE does not tell us the cause of the cardiomyopathy… it simply means a small amount of heart muscle died from the acute process (myocarditis due to any cause, MI, etc.)

https://twitter.com/cshenoy3/status/1194307146332221442?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh