When World War I ended with an Armistice, many @USArmy officers were surprised. The situation seemed “unfinished” and there was concern that another war was imminent.

“Among many of the front-line troops in the Allied armies there was… an ambivalent mood, elation at the end of hostilities yet frustration that the victory was somehow muddied by a sense that Germany was still on its feet, bloodied but unbowed.”

“Among the AEF [American Expeditionary Forces] there was a widespread sense of having been cheated of real triumph.”

General Pershing, on the day of the Armistice, 11 Nov 1918, told his aide, “I suppose the campaigns are ended, but what an enormous difference a few days would have made.”

The following year, then-Lieutenant Colonel Walter Krueger noted that he hoped the lessons learned from WWI would not be wasted and we would not abandon the efforts to maintain necessary readiness. @USArmy_CALL @ArmyUPress

Krueger was concerned that the American public would not see a need for supporting military readiness because we had shown that we could raise a large army in a short period of time. “We of the army… ought to be heard.”

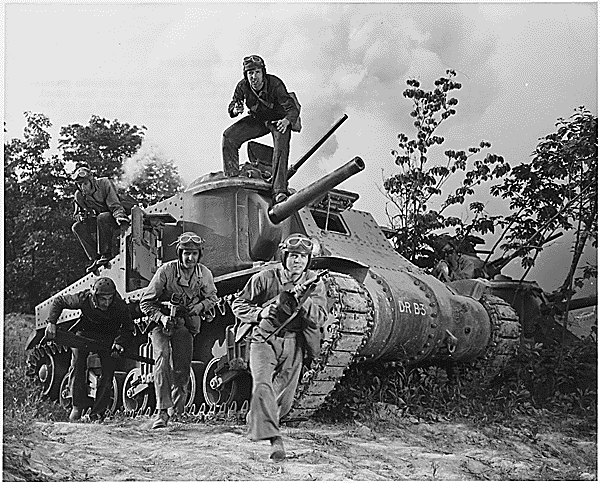

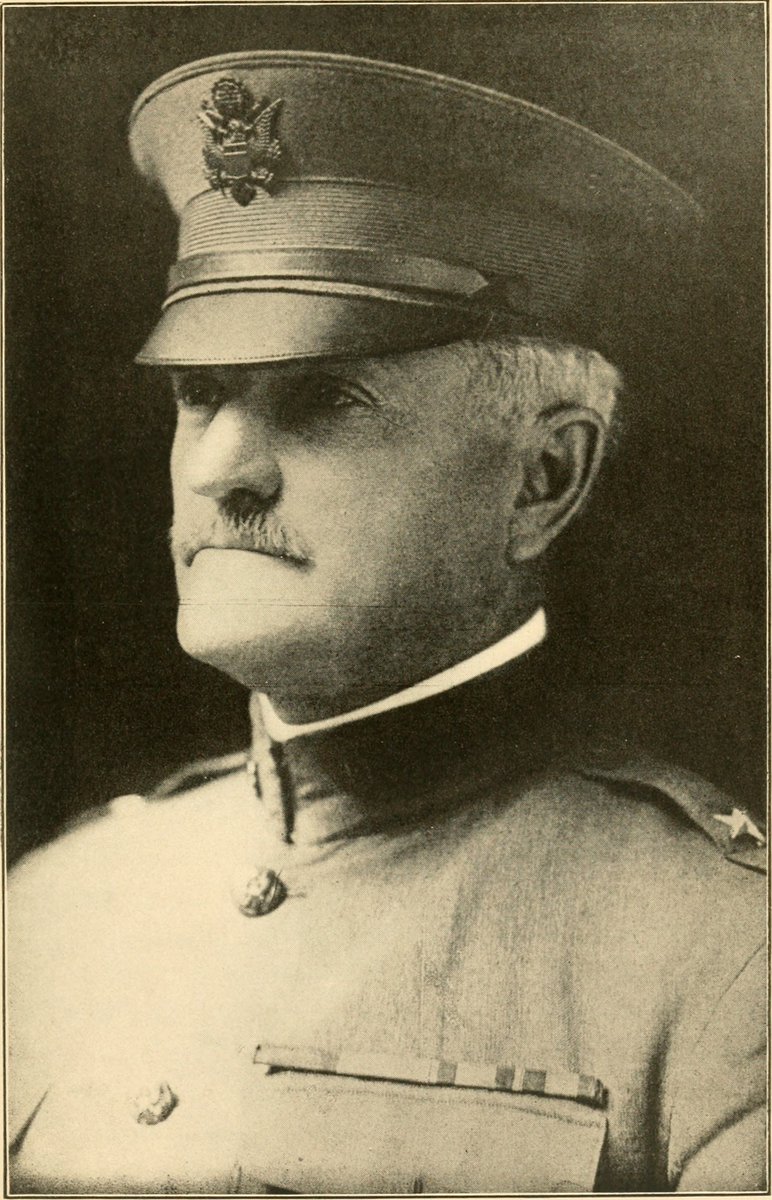

(Krueger, MacArthur, Marshall)

(Krueger, MacArthur, Marshall)

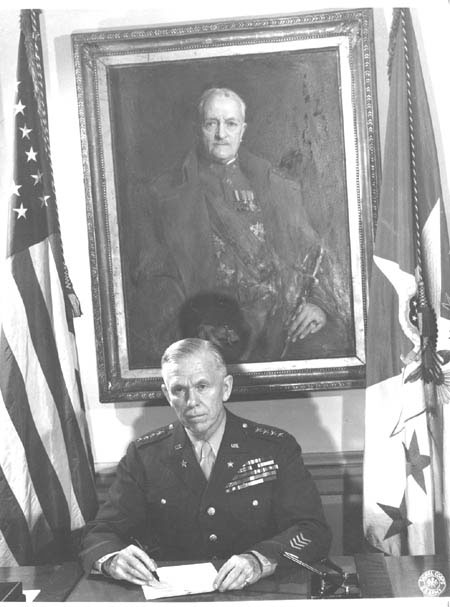

Marshall was concerned that the Armistice would have a negative impact on our national security posture. Like many others in the @USArmy, Marshall had wished the end of WWI had been more decisive.

But as far as the American public was concerned, the war with Germany was over and thus there was no longer a need to send our military overseas.

“In less than 18 months, the AEF created two armies, ten corps, and 26 divisions, and engaged these new large formations in offensive combat operations against German defenses.”

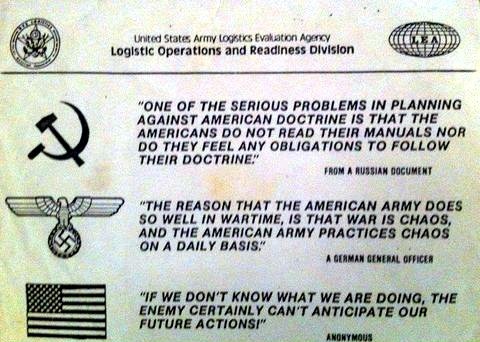

“These offensive combat operations came at a significant cost and engendered a reluctant appraisal by Army officers of their incompetence at the essential tasks of modern war: planning, logistics, organization, and the handling of large formations.”

Pershing knew that the next war was going to be greater and require the mobilization of the entire nation, not just rebuilding an army. From his address to the graduating @USACGSC class of 1920:

“It would seem pertinent to emphasize the great importance of general staff instruction and its bearing upon the future war efficiency of the army. Indeed, we should say upon the war efficiency of the country, for it is the nation with all its resources… that makes war.”

The National Defense Act of 1920 brought significant changes to the US military, with a new focus on having a smaller Regular Army that could serve as a “schoolhouse” for @usnationalguard and @USArmyReserve – but the Army would still suffer significant shortages of funding.

A large officer corps would be necessary for providing instruction but due to the conditions following WWI, and the lack of funding and shortage of personnel saw many overworked.

Brigadier General Hanson Ely, commandant of @USACGSC from 1921-1923, testified before an appropriations committee in 1923:

“The officers who are sent there as instructors are among the keenest men in the Army, and I now work those officers up to 11 and 12 o’clock at night for about five nights in the week.”

“It is my desire, if I can, to reduce the work of these instructors down to the equivalent of the work of ordinary officers in the army…”

“On account of the lack of money we cannot hire stenographers, so I say to them, ‘You have got to do this work, it must be done by a certain time; here is a typewriter, go to it.’ And they pick on a typewriter with one finger, and that is what they are doing now.”

Working the men longer didn’t cost the government anything extra so this was viewed as an "acceptable enough" solution for the short term, while money and public support were in short supply.

In 1929, the Infantry Journal noted that about half of the Field Grade Officers and Captains in the Infantry Branch were either assigned as instructors or as students within the officer education system.

One in 10 was at a Branch School, one in 20 at @USACGSC or at the @ArmyWarCollege, and about half were teaching @usnationalguard, @USArmyReserve, or @ArmyROTC.

It was difficult for many to shift from what they viewed as traditional Army life, being amongst and leading troops, to what was becoming the new normal with many in instructor or student roles.

General Pershing helped shift this mindset with his push for developing a “new form of professionalism in the officer corps.”

Speaking to the @ArmyWarCollege class of 1923, Pershing said:

“In no other army is it so imperative that the officers of the permanent establishment be highly perfected specialists, prepared to serve as instructors and leaders for the citizen forces which are to fight our wars.”

“In no other army is it so imperative that the officers of the permanent establishment be highly perfected specialists, prepared to serve as instructors and leaders for the citizen forces which are to fight our wars.”

“The one-time role of a regular army officer has passed... Our mission today is definite, yet so broad that few, if any, have been able to grasp the possibilities of new fields opened up by the military policy now on the statute books…”

“There are officers, fortunately in constantly diminishing numbers, who cannot turn their minds from concentration on a diminutive regular army, successfully and gallantly fighting the country’s battles in Cuba and the Philippines, or serving at isolated stations…”

“Those days have not entirely passed away, and probably never will pass, but they are now of secondary importance in the general scheme of National Defense.”

It also helped that Congress was willing to approve spending for officer education, even if resistant to spending money on a large standing force.

Many professional military journals would receive and publish articles from officers discussing the importance of teaching during peacetime: “teaching duty… in peacetime… was not only necessary but also natural for army professionals.”

Some officers wrote articles that argued against this focus. For example, the May 1921 edition of Infantry Journal published an article by an Army Major entitled “Who is Going to Soldier when Everybody is Going to School?”

Another officer wrote a response to that article, saying the Major misunderstood the purpose of the officer education system. “The system was designed not only to begin the education of officers but also to require officers to continue self-development for their entire careers.”

Articles also included suggestions for adding books to personal libraries for professional reading, much like we still see now with reading lists from @TheCompanyLDR @FieldGradeLead @mil_LEADER @FTGNotebook @Doctrine_Man @warinstitute and many others.

The money that was given to the @USArmy for reinforcing the officer education system allowed the Army to build larger school facilities during the Interwar Period. @MastersManeuver @FortBenning @USAFAS

When spending tightened with the Great Depression, the General Staff was willing to sacrifice almost anything except the “training basis of the mass army” including the officer corps and Army schools.

More to come on the topics of Army Education! And as always, if you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh