What is the trajectory of viral load dynamics & test sensitivity post-INFECTION?

We're 17 month into the pandemic &, shockingly, this Q is still only partly answered.

Recent paper using a study design I proposed 12 months ago provides detailed look & raises many questions.

We're 17 month into the pandemic &, shockingly, this Q is still only partly answered.

Recent paper using a study design I proposed 12 months ago provides detailed look & raises many questions.

Background

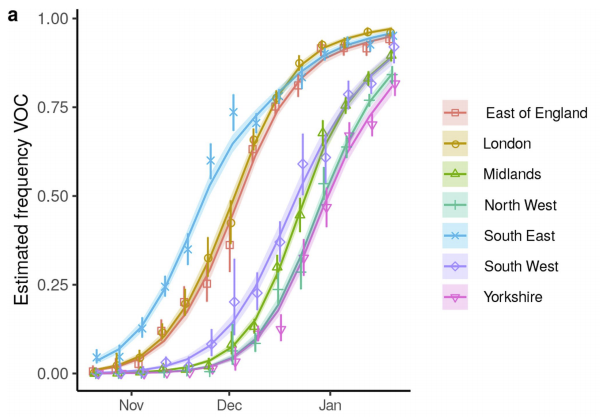

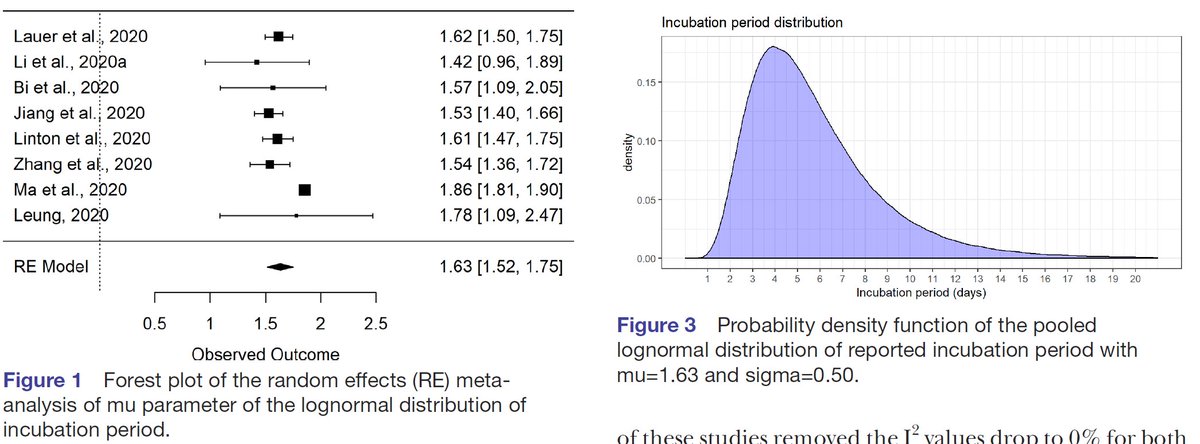

We know that ~3-6d following infection COVID-19 symptoms start (the incubation period). doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2020-039652

We know that ~3-6d following infection COVID-19 symptoms start (the incubation period). doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2020-039652

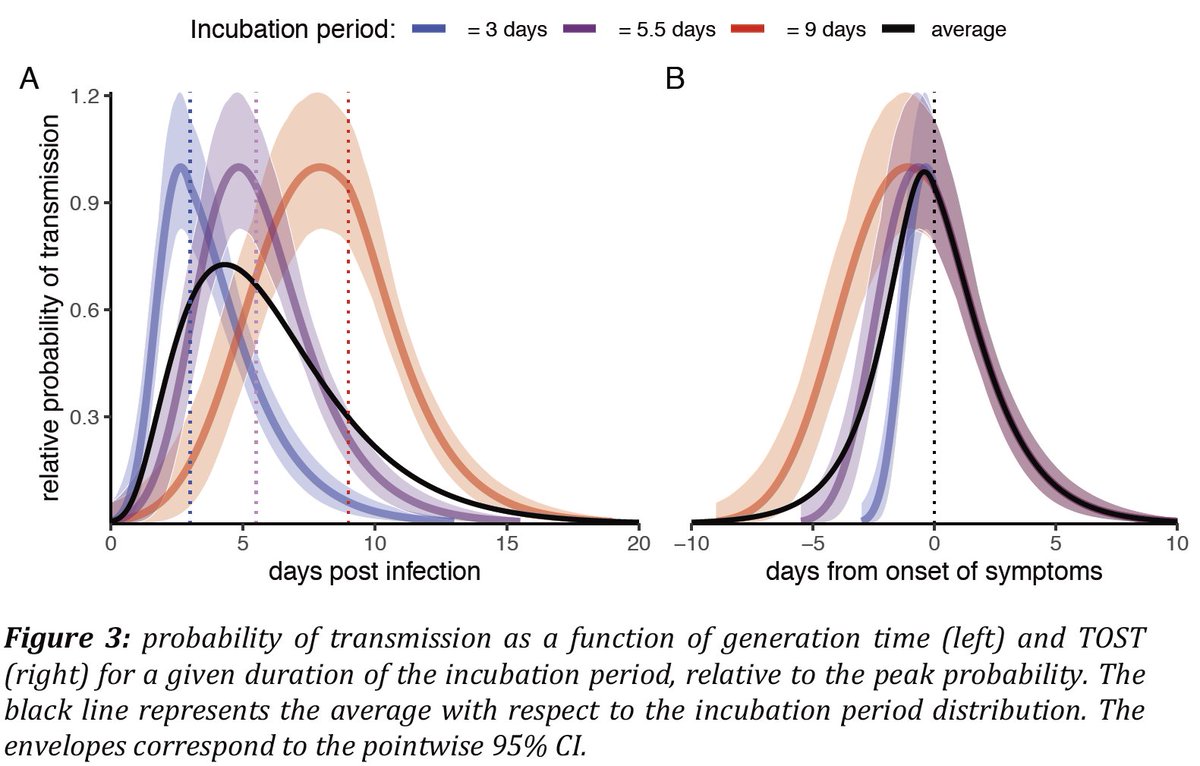

We also know that people are infectious before symptom onset - this has been one of the greatest challenges in controlling SARS-CoV-2.

In fact, we even know some details: we know that the longer the incubation period the longer the pre-symptomatic infectious period. Fig from our work w/ @LucaFerrettiEvo @ChrisWymant @ChristoPhraser @mishkendall @JoannaMasel doi.org/10.1101/2020.0…

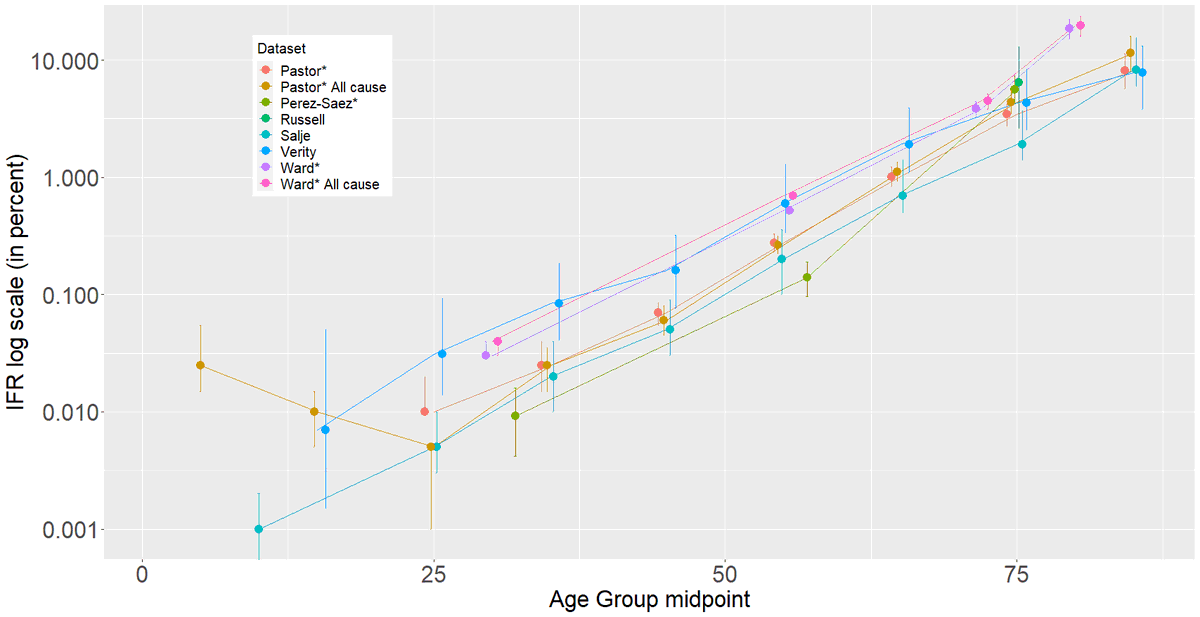

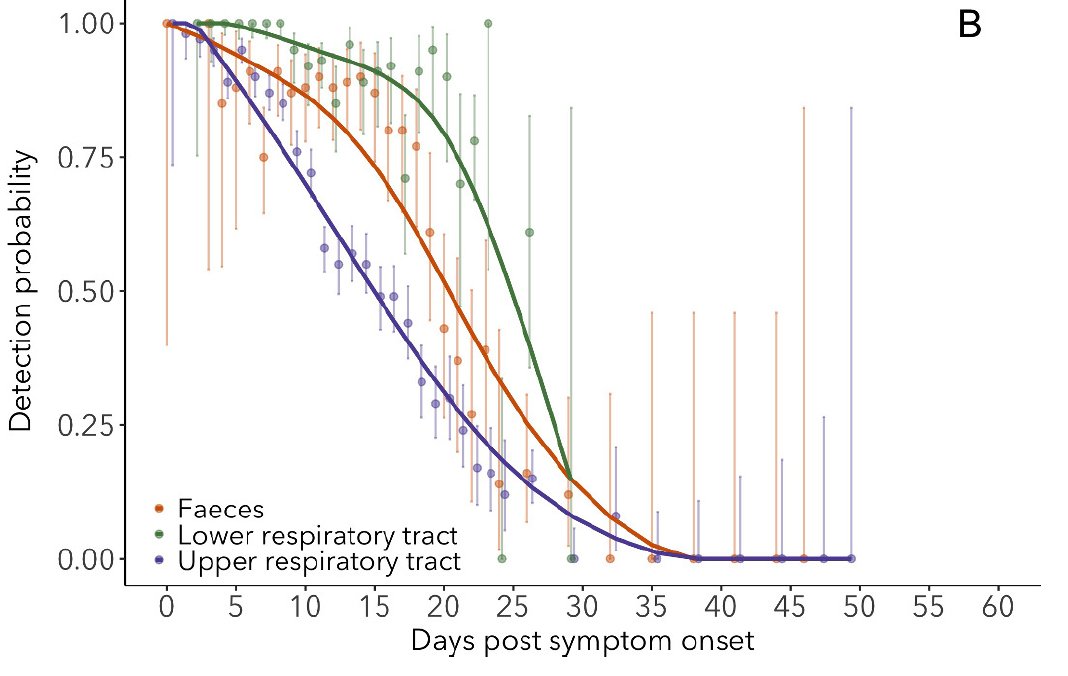

However, the detailed dynamics of viral loads before symptom onset are still poorly known, despite their importance. Meta-analyses of viral loads or test sensitivity are data-rich starting at symptom onset (Fig), but very data-poor before. @bennyborremans doi.org/10.7554/eLife.…

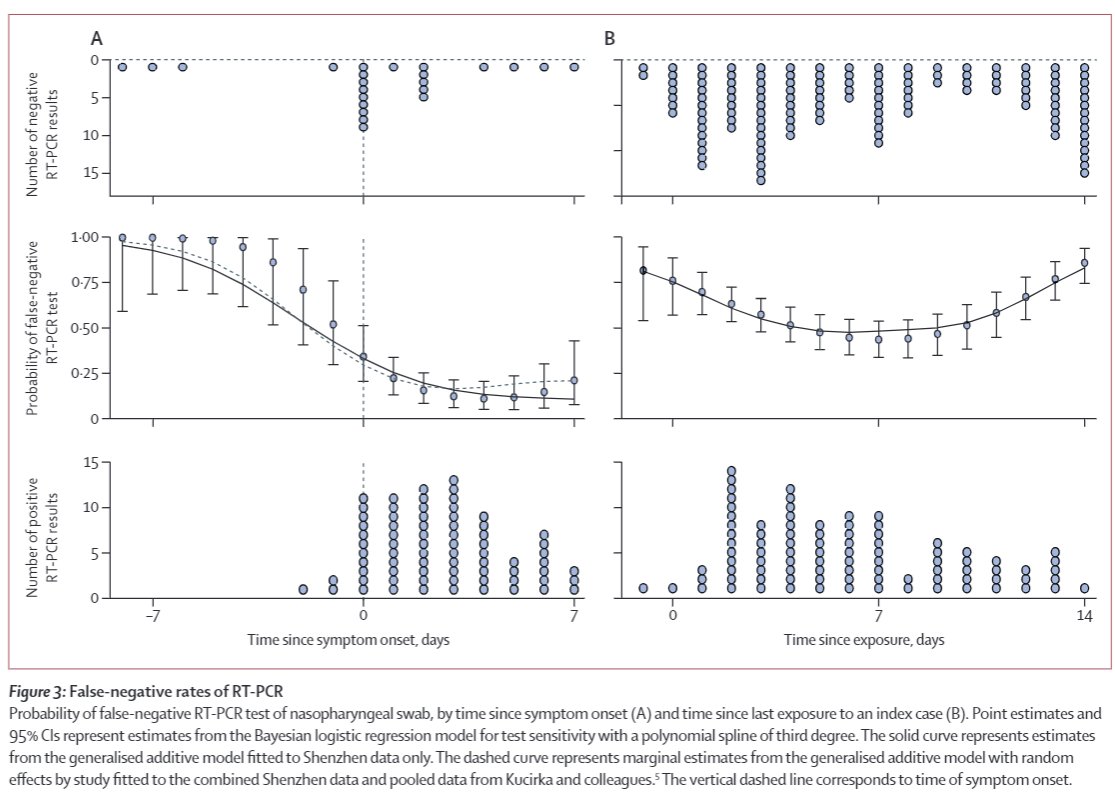

Here's another paper on test sensitivity. Note extreme sparsity of data before symptom onset.

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

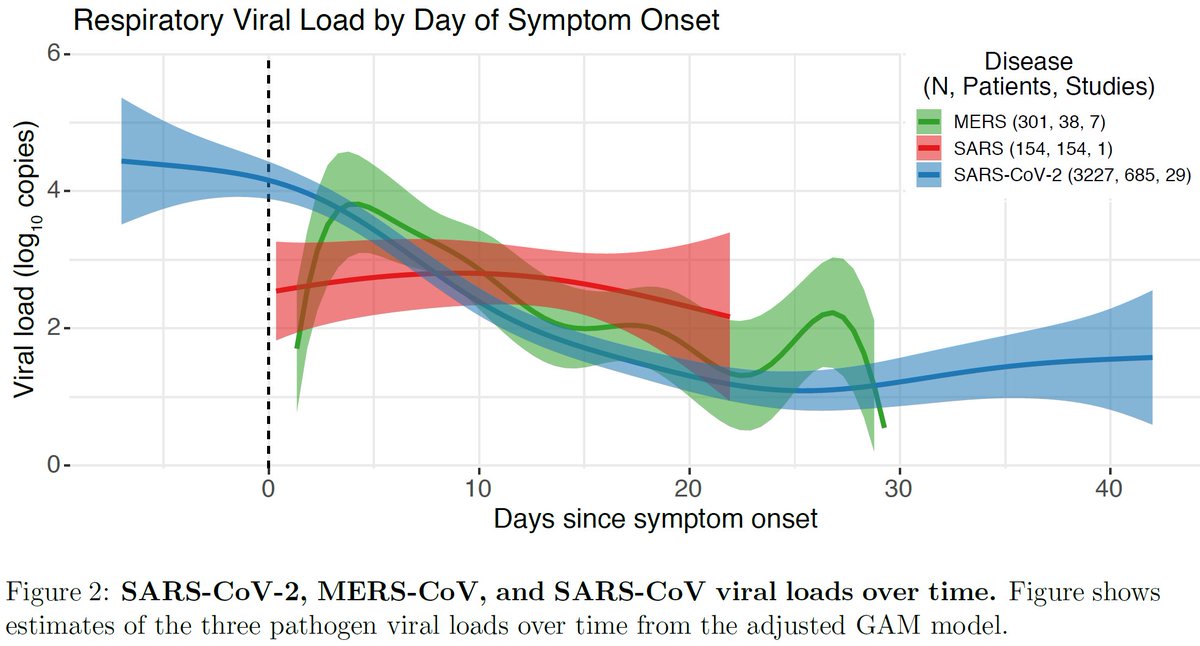

Here's a meta-analysis of viral loads. Note the wide CI before 0 due to sparse data.

doi.org/10.1101/2020.0… @BMAlthouse

doi.org/10.1101/2020.0… @BMAlthouse

But wait: some of you may know of great NBA paper that had detailed viral loads from frequent swabbing. Unfortunately, this study didn't have the date of infection or day of symptom onset. @yhgrad @StephenKissler

doi.org/10.1101/2020.1…

doi.org/10.1101/2020.1…

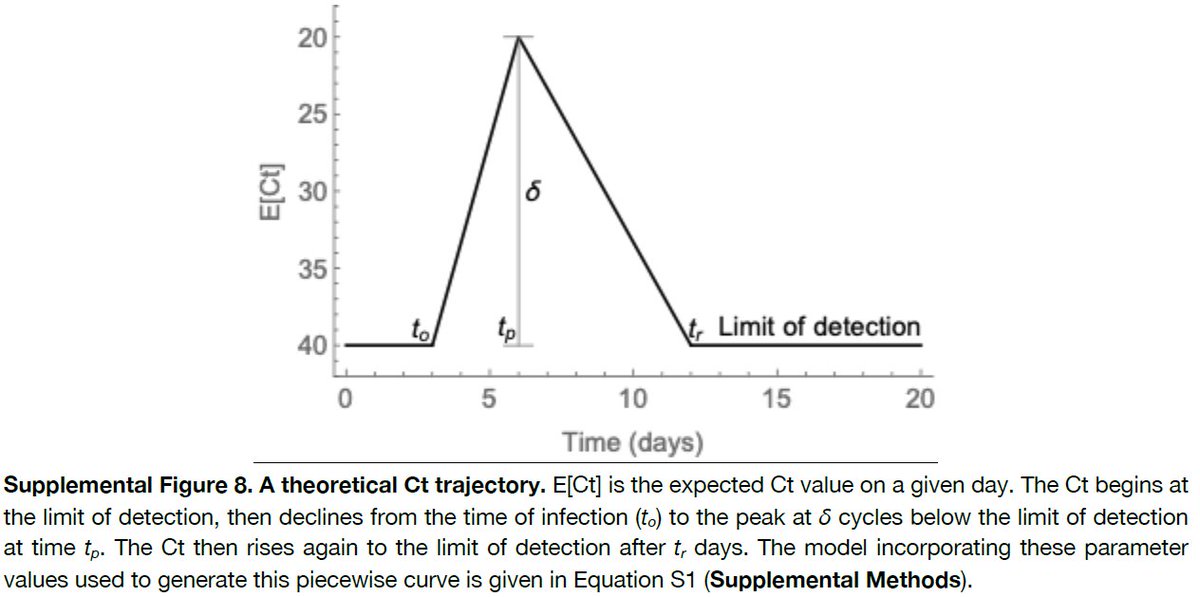

As a result, they modeled a theoretical viral load trajectory, but couldn't scale it to time since infection or symptom onset.

You may be wondering, if we know the infectiousness pattern vs time since infection, why do the viral loads it matter? Many reasons, but the most important is because they determine test sensitivity over time. I've been writing about this since June 2020:

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1270093309126438912

Testing is still being used to screen people for travel, entry into events, schools, etc. Thus it's crucial to know how good tests are at finding infected people vs time since infection.

Here's an attempt to gather data on viral loads & live virus to estimate the infectious period from June 2020:

In October 2020 I again lamented lack of pre-symptom onset data:

& an article @sarahzhang theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1271281847754846211

In October 2020 I again lamented lack of pre-symptom onset data:

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1312537935892246528

& an article @sarahzhang theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

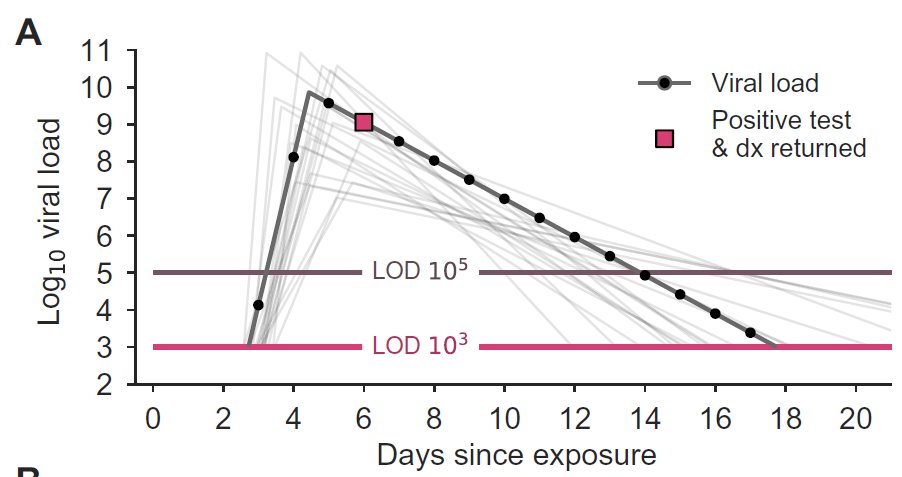

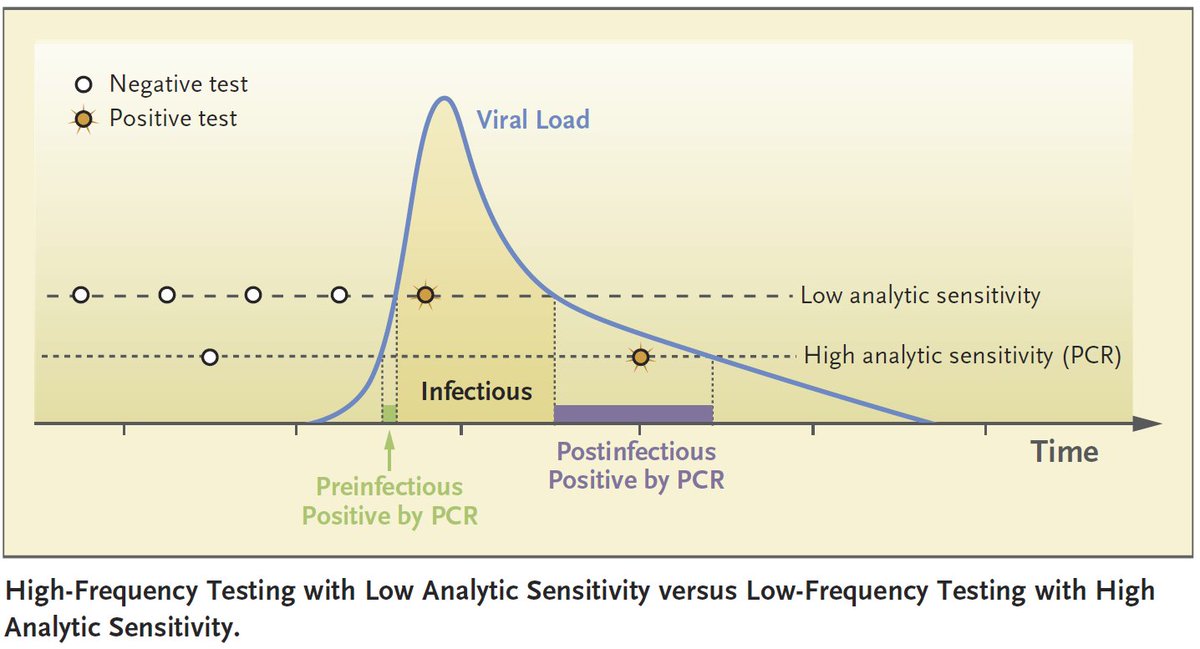

Lots of theory on how test sensitivity determines the effectiveness of frequent testing to reduce transmission. Most papers have used models like this of viral loads. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abd5393

@DanLarremore @michaelmina_lab

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2025631

@DanLarremore @michaelmina_lab

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2025631

But none of these papers have viral load data on the rise in viral loads relative to days since exposure & symptom onset. They simply don't exist. But why? The study design to collect these data is pretty simple. I laid it out in detail June 8, 2020:

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1270093322921455617

In short: Collect daily swabs from recent close contacts of cases over time, and keep swabbing after initial detection until virus is no longer detectable. Unfortunately I never saw a paper that used this approach. Until today! (h/t @profshanecrotty)

Here's the paper:

medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

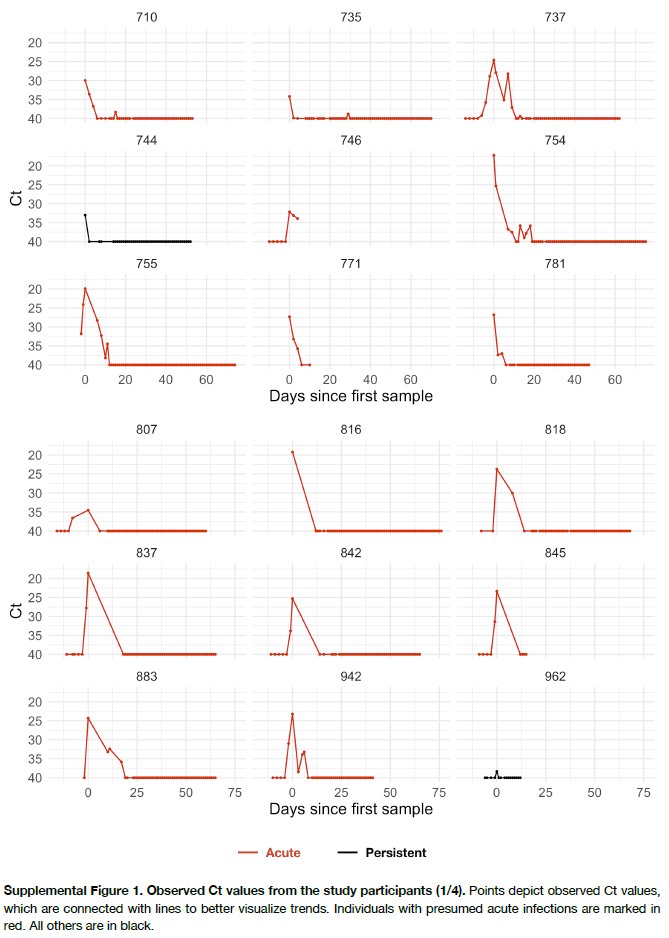

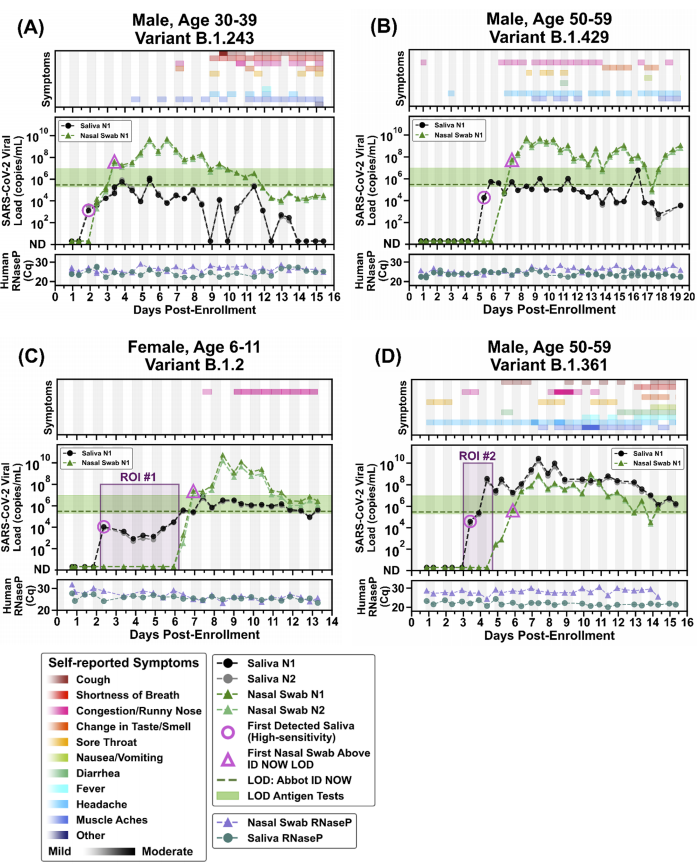

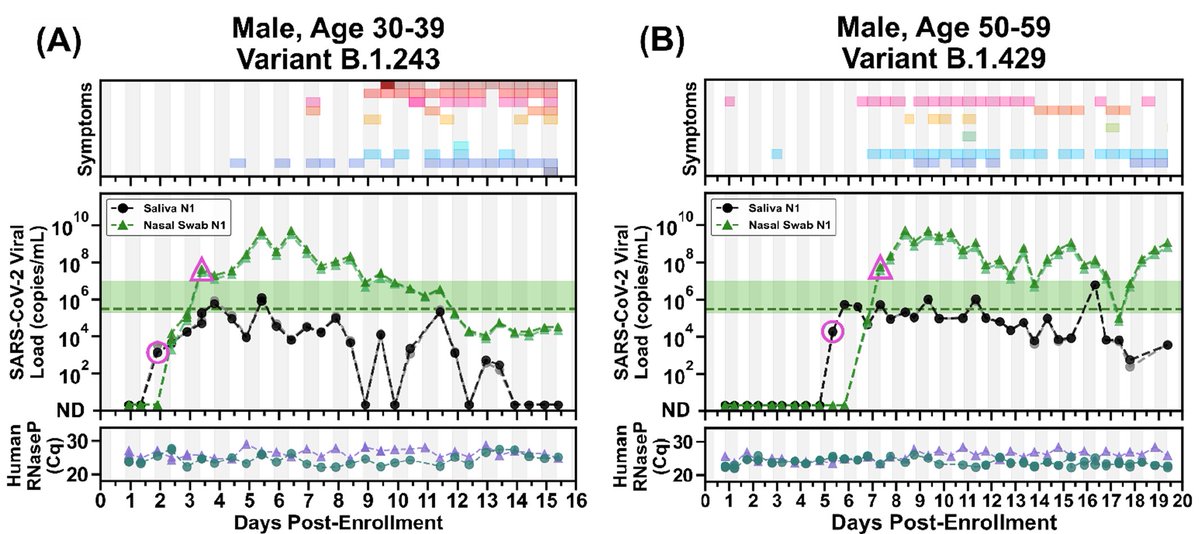

Here's the amazing data. Twice (!) daily nasal (NOT NP) swabs & saliva, detailed 2x daily symptom diary & human DNA as control for swab/saliva quality. Absolutely fantastic. Unfortunately, 1 giant caveat: only N=4 people in study. Despite this, many interesting patterns & Qs.

1st: substantial differences in saliva vs nasal swab viral load trajectories (one is not always higher than the other). Virus detected in saliva 1st, 1-5d earlier than nasal swabs, but most nasal load swabs much higher than saliva for 3/4 people. What produces these patterns?

2nd: Long (5.5d) period of virus detected in saliva but not nasal swab, for 1 person (young child). Is this common in children?

3: Highly variable symptoms w/ patchy onset relative to viral loads. Makes symptom checks challenging!

3: Highly variable symptoms w/ patchy onset relative to viral loads. Makes symptom checks challenging!

4: viral loads almost always higher in morning than at night (noted by @profshanecrotty). Why is this? Because person was laying down before sampling? Does this increase infectiousness or just test sensitivity?

5: Paper argues saliva is better than nasal swabs (+s earlier) but it requires high sensitivity test to detect virus. Many saliva samples were below rapid test detection limit (green shading, dashed line). Thus paper argues against using less sensitive rapid tests .

But as @michaelmina_lab has tirelessly argued, rapid test done daily would catch people when infectious & would be preferable unless sensitive PCR could also be done daily & return results quickly (w/in 24 hrs).

Also, it's not clear if low-moderate saliva load is infectious.

Also, it's not clear if low-moderate saliva load is infectious.

Are there data comparing viral loads in saliva vs loads in nasal swabs in predicting secondary attack rates (e.g.

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1359213763199598594)? I haven't seen a study doing so but it would be useful to answer question of whether moderate saliva loads imply infectiousness.

Also, although paper argues saliva is better, saliva testing here required sampling at least 30 min after any eating/drinking which is difficult to implement in general population.

Summary: Lots of cool patterns & unanswered Qs. We need this kind of data for a few more dozen more people of varying ages. I hope this study will be replicated soon!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh