Months ago, I promised to do a follow-up thread on this series of comparisons between Nabataean Arabic and Old Hijazi. I said I would discuss the so-called Barth-Ginsberg alternation, this concerns the prefix vowel of verbs.

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1359473476462120961

The medieval Arabic Grammarians tell us that the prefix vowel of verbs may be either /i/ or /a/, which is conditioned by the following vowel. If the vowel is /u, i/ the prefix vowel is /a/, and if the vowel is /a/, the prefix vowel is /i/.

- niʿlamu, nistaʿīnu

- naktubu, nafqidu

- niʿlamu, nistaʿīnu

- naktubu, nafqidu

This alternation affects the prefix 1sg. ʾa/ʾi-, 1pl. na/ni- and the feminine or 2nd person ta/ti-. The masculine prefix ya- is said to be exempt from it (except for some contexts). Thus:

- ʾaktubu, taktubu, naktubu, yaktubu

- ʾiʿlamu, tiʿlamu, niʿlamu, YAʿlamu

- ʾaktubu, taktubu, naktubu, yaktubu

- ʾiʿlamu, tiʿlamu, niʿlamu, YAʿlamu

Sībawayh tells us that the a in both contexts is something specific to the people of the Hijaz. All other Arabs have the alternation.

Al-Farrāʾ is more specific: Quraysh and Kinānah lack the alternation while the majority of Arabs of Tamīm, ʾAsad, Qays and Rabīʿah have it.

Al-Farrāʾ is more specific: Quraysh and Kinānah lack the alternation while the majority of Arabs of Tamīm, ʾAsad, Qays and Rabīʿah have it.

Having the alternation is the original archaic situation. It has clear parallels in Hebrew, for example. There is in fact where it was first described (by Barth and Ginsberg, hence Barth-Ginsberg alternation):

yɛhɛ̆raḇ < *yihrabu

yaḥăroš < *yaḥrušu

yɛhɛ̆raḇ < *yihrabu

yaḥăroš < *yaḥrušu

The generalization of the /a/ vowel to all verb stems is a typical innovation of the Hijazi dialect.

It is not easy to see what system Nabataean Arabic would have had as short vowels are not written in Nabataen.

In the Graeco-Arabic material from the region we find some traces.

It is not easy to see what system Nabataean Arabic would have had as short vowels are not written in Nabataen.

In the Graeco-Arabic material from the region we find some traces.

We can thus carefully conclude that Nabataean Arabic probably did not undergo the Hijazi innnovation generalizing the /a/ vowels. But what about Quranic Arabic? Does it align itself with the the majority of the dialects or with Hijazi Arabic?

This is not easy to deduce as the Quran was written without vowels. The canonical reading traditions today all read it in the Hijazi manner. But things used to be different. al-ʾAʿmaš, teacher of the canoncial teacher Ḥamzah had this alternation (but not in 1st person sg.)

However, for some verb types, the prefix vowel has an effect on the consonantal skeleton. The grammarians tell us that a verb like wajila 'to be afraid' surfaces as:

ʾawjalu, tawjalu, nawjalu, yawjalu in Hijazi

but: ʾījalu, tījalu, nījalu, yījalu in the other dialects.

ʾawjalu, tawjalu, nawjalu, yawjalu in Hijazi

but: ʾījalu, tījalu, nījalu, yījalu in the other dialects.

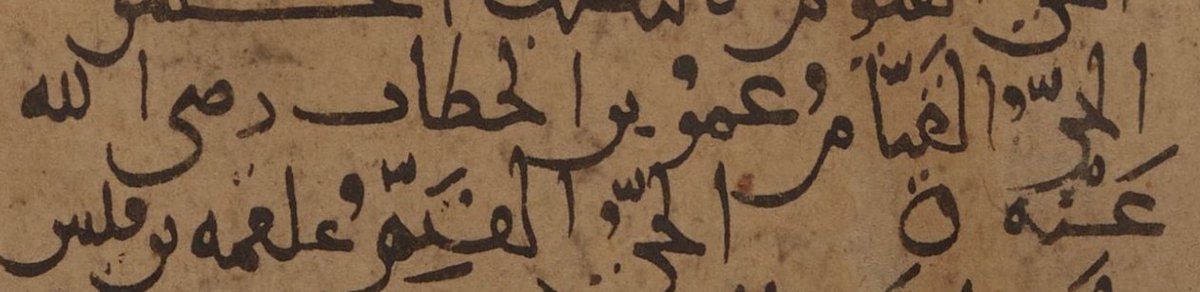

lā tawjal "don't be afraid" occurs in the Quran (Q15:53), so we can check! If it is spelled لا تيجل Quranic Arabic had the alternation, if it is لا توجل it underwent the Hijazi innovation! It is consistently spelled لا توجل, thus the consonantal text supports a Hijazi reading!

Interestingly in these kinds of verbs, the 3rd person masculine prefix is said to also be included in the alternation. This is probably an indication that, despite the prescriptive standard saying that the form is yaʿlamu even for those that say tiʿlamu, it once was yiʿlamu too.

In terms of this isogloss, then, the Quran is once again a document that was clearly composed in Hijazi Arabic, and seems to have been distinct from Nabataean Arabic (and other northern dialects) as well.

It is interesting to note that, several modern dialects actually retain the Barth-Ginsberg alternation as reported by the Arab grammarians (though always including yi- in it as well, but surprisingly not ʾi-). This is clearest in some Najdi dialects.

In a recent article I've argued that Maltese (and Tunis Arabic) in fact also retains traces of this original alternation, and, strikingly, just like Hebrew retains that distinction before guttural consonants!

Most modern dialects generalize the i-vowel to all stems.

Most modern dialects generalize the i-vowel to all stems.

The Hijazi practice, which becomes dominant in the Classical standard, leaves almost no trace (if at all) in the modern dialects. One wonders whether it became so popular specifically because it was so unlike the vernaculars and thus must have surely been "proper".

There are some more isoglosses that distinguish Hijazi Arabic from epigraphic North Arabian, such as verb stems. I'll discuss those next.

If you enjoyed this thread, please consider buying me a coffee: ko-fi.com/phdnix

Or become a patron on Patreon: patreon.com/PhDniX

If you enjoyed this thread, please consider buying me a coffee: ko-fi.com/phdnix

Or become a patron on Patreon: patreon.com/PhDniX

Here's the a-/i- prefix alternation thread I promised @lawzinaj ! :-)

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh