I'm always conflicted about the question of normalizing spelling in text editions. @bdaiwi_historia is right that this is standard practice for Classical Arabic text editions, but for linguists, this practice erases or distorts the history of a language, including Arabic.

https://twitter.com/bdaiwi_historia/status/1391069479443091463

Normalizing of spelling has long been a standard practice in a lot of philological fields, but in Indo-European Linguistics, my original field of study, people have been moving away from it.

This is because essential distinctions between, for example, Old Swedish and Old Icelandic only started becoming salient once text editors stopped normalizing everything towards an ideal "Old Norse" described in the grammars of the early philologists.

In Arabic, this practice had led to a rather artificial boundary at times becoming drawn between Christian and Islamic Arabic, where all kinds of orthographic practices are described as "typically Christian" because they do not show up in Classical Arabic text editions.

e.g. Christian Arabic is supposedly different from Classical Arabic in that the vocative yā before a word that starts with ʾalif is wriyten without the ʾalif, e.g. yā-ʾādam is not يا آدم but يآدم. But you find it in Ibn Ḫālawayh's kitāb al-Badīʿ. But erased in the text edition.

Because of standardization, I have no idea if this manuscript is a strange exception, or whether Middle Arabists are simply wrong in assuming that text editions are accurate representations of what you find in the manuscripts (which for Christian Arabic *is* mostly the case).

Normalizing the spelling of manuscripts towards Modern Standard Arabic norms also means that people forget or simply misunderstand the medieval norms of spelling. I have not found a single description that accurately describes the use of the Maddah sign in Classical Manuscripts.

That occasioned me to write this article on it:

brill.com/view/journals/…

But there is much more, I have a forthcoming article that uncovers different reading traditions of dalāʾil al-ḫayrāt, systematically marked in vocalized manuscripts of the texts.

brill.com/view/journals/…

But there is much more, I have a forthcoming article that uncovers different reading traditions of dalāʾil al-ḫayrāt, systematically marked in vocalized manuscripts of the texts.

It turns out that copies made in Mali closely follow the ʾuṣūl of the Quranic reader Warš. Those made in Morocco follow some principles, but deviate in other places making them a clearly distinct tradition. Turkish manuscripts follow a Ḥafṣ-like tradition.

All of that highly salient linguistic material, which teaches us something about the use and context of the manuscripts produced is lost by normalizing these spellings. There's more interesting details that I'll hopefully publish on in the future like that...

Even when text editions claim to be critical editions, and are thus supposed to systematically show the differences between manuscripts, spellings still get normalized, even if a manuscript tradition *consistently* deviates from a textual norm.

In several manuscripts of al-Dānī's taysīr, the name ʾAbū Laylā is not spelled أبو ليلى as modern norms would require, but instead they have أبو ليلا (or well, أبي ليلا). To a non-linguist this might not mean much, but for me this immediately rang a bell:

In the oldest forms of Arabic, the vowel -ā written with ʾalif and the one written with yāʾ used to be pronounced differently. The former as /ā/ (e.g. دعا as /daʿā/) while the latter as /ē/ (e.g. هدى as /hadē/). The name ليلى would thus be expected to be /laylē/...

@Safaitic noticed that in Pre-Islamic Greek transcriptions of Arabic names the distinction between /ā/ and /ē/ is consistently made. However, there was one exception: laylā!

This exceptional status of the pronunciation of laylā seems to be remembered in the ليلا spelling!

This exceptional status of the pronunciation of laylā seems to be remembered in the ليلا spelling!

But it is difficult to make the case based on one pre-Islamic papyrus and three 17th~18th century Arabic mansucripts that ليلا is indeed the typical (or at least common) spelling. I would want to check other, older texts. But due to normalized spelling, this is impossible.

Now, I do understand the uses of normalized spellings. Not everyone is coming at these texts as linguists/philologists, and having all of these texts rendered in a general standardized way for everything is of tremendous use for accessibility to a very broad audience...

But it is important to realize what we are losing in the process. Much of the myths about a standard, unchanging standard Classical language from the beginning of Islam until today stem from the destructive way in which any feature of interest is stamped out of editions.

Besides writing the history of Islam, which one does by making these manuscripts accessible, we must also write a history of the primary language of Islam. At the moment that is very essentially impossible. It's in fact easier to do for Christian Arabic and documentary papyri...

wheere the philological editing practices are more aligned to conducting this kind of research. But due to the mismatch in practice between these two groups is only seldom appreciated, as a result the differences is presented to be much bigger than it actually is.

I don't know what the answer is, but I'll finish with a final thought. Quranic orthography is *very* different from normative Classical Arabic orthography, and obviously something of a transition happened between the earliest period and the Classical tradition.

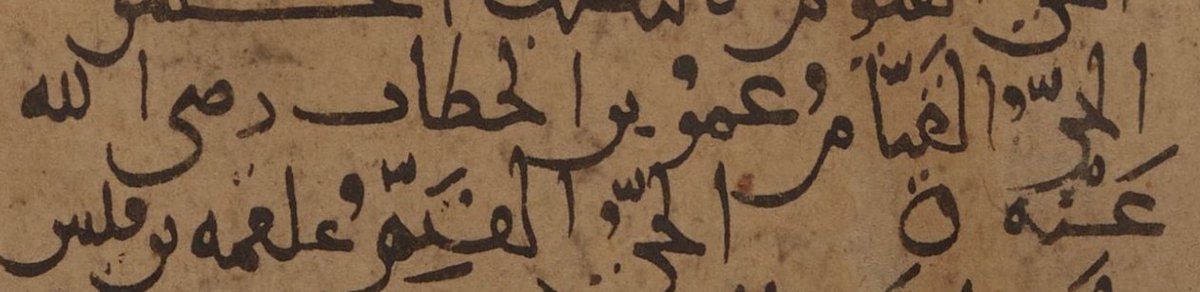

This transition is totally erased in the Classical manuscript editions due to normalization. But if one looks at Or. 298 (252 AH), you can still see a transitional stage, e.g. tarā-hā spelled تريها not تراها.

…italcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/2000…

Do we really wanna lose these insights?

FIN

…italcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/2000…

Do we really wanna lose these insights?

FIN

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh