@IntOrgJournal's 75th anniversary special issue on "The Liberal International Order" largely omits international security affairs.

This leads me to ask: What Would Hedley Bull Think? 🤔

[THREAD]

This leads me to ask: What Would Hedley Bull Think? 🤔

[THREAD]

To be fair, the special issue covers a range of important topics facing the world (e.g. climate change) and the editors fully acknowledge the omission of security affairs.

But they justify the omission by saying that security institutions, namely @NATO, seem to be just fine.

But they justify the omission by saying that security institutions, namely @NATO, seem to be just fine.

One could take issue with the claim that security institutions are presently "alive and kicking" (moreover, the editors even acknowledge that the nuclear nonproliferation regime is "under siege")

politico.com/news/2021/06/1…

politico.com/news/2021/06/1…

But regardless of the current state of global security affairs, Hedley Bull would likely have found the limited discussion of security affairs in an issue about "order" to be curious.

Why should we care what Bull thought? Well, Bull was a key thinker on the concept of "international order"

Why would Bull have found the omission of security affairs from a special issue on "order" to be curious?

Because security issues -- arms control in particular -- were central to Bull's conception of order.

Because security issues -- arms control in particular -- were central to Bull's conception of order.

Bull started publishing in the 1960s.

Like Realists (see #KeepRealismReal threads), Bull began his intellectual efforts by thinking about disarmament and arms control negotiations.

Like Realists (see #KeepRealismReal threads), Bull began his intellectual efforts by thinking about disarmament and arms control negotiations.

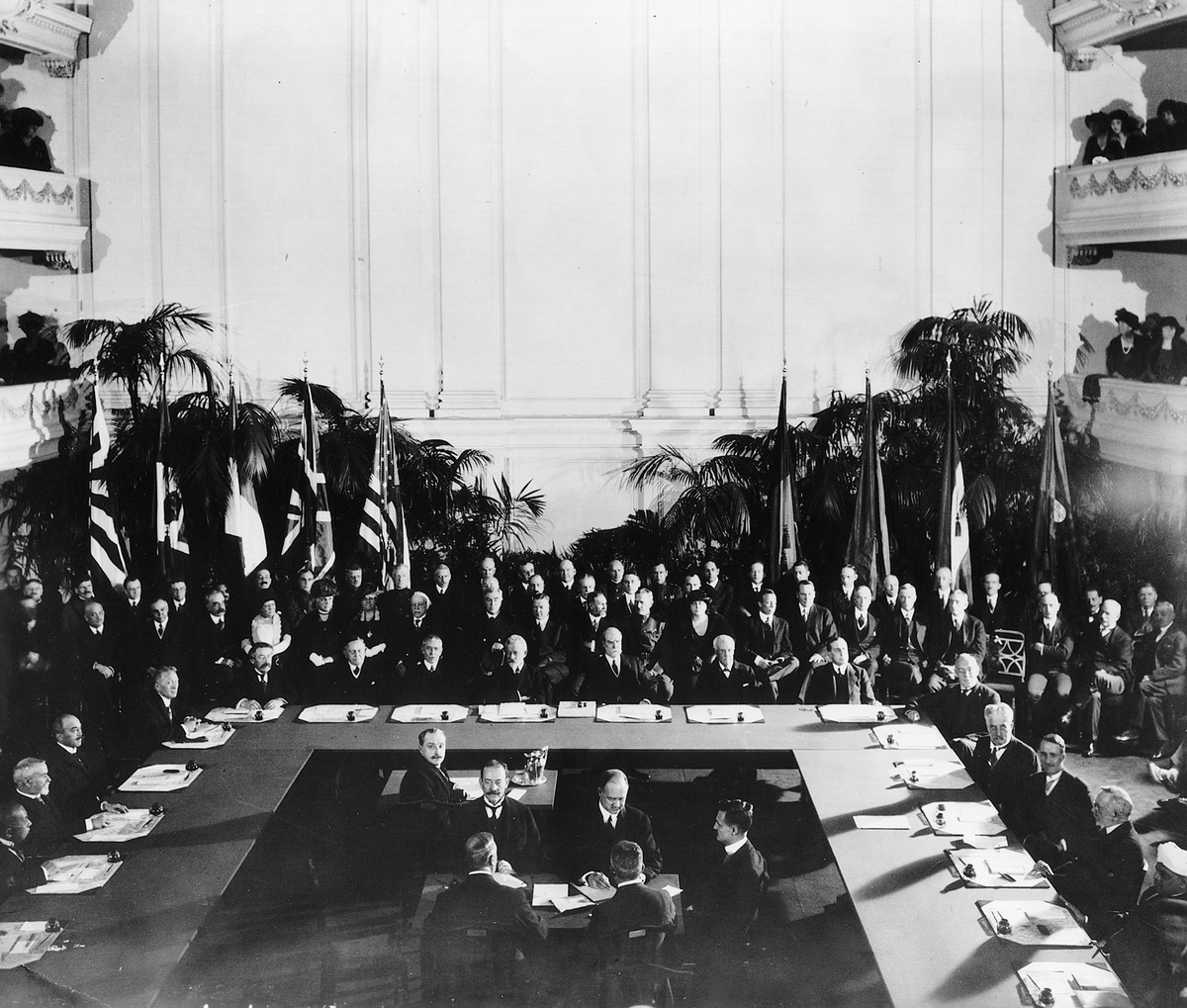

His first book, The Control of the Arms Race (1961), examined "the controlled reduction of armaments", which lies at the intersection between disarmament -- the reduction or abolition of arms -- and arms control -- restraint of arms.

amazon.com/control-arms-r…

amazon.com/control-arms-r…

Thinking about these issues would eventually inform how he thought about a larger topic -- and the topic for which he is best known: international/world order

The connection between "arms control" and "order" is made clear in his 1976 @Journal_IS piece, "Arms Control and World Order" (which was actually the first ever article in IS).

jstor.org/stable/2538573…

jstor.org/stable/2538573…

And this leads to one of my favorite statements on world order -- it is NOT about moving beyond the state (say to a world government)

In the footnote at the end of that sentence, he states how his forthcoming book -- The Anarchical Society -- will flesh-out this claim.

That leads to his next big concept - "international order" (which, unlike the the above IS piece, he distinguishes from "world order" -- which is about humans, not states).

What does Bull mean by this definition of order? He gives a more detailed definition: it's about common interests/goals, rules, & institutions.

A "common goal" for the present international order is maintaining the sovereign existence of states

https://twitter.com/ProfPaulPoast/status/1398238661322416135

A key "rule" of the present international order is defining the terms by which violence can be used:

Order does not (and cannot) eliminate violence in the international system: a point Bull makes (unsurprisingly, given his arms control research)

His "not impressed" attitude toward the existing order makes sense: the book, published in 1977, was his attempt to make sense of the "upheaval of the 1970s". What challenges were facing the world at that time? Bull lists them:

So, in addition to questioning the omission of security issues, the "Liberal International Order" framing at the beginning of the IO special issue would also have gotten a 🤔 from Bull

In sum, given his focus on arms control and his recognition of ever present violence in the international system, Bull would have found the lack of security affairs in the IO special issue to be highly curious.

[END]

[END]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh